Letter reveals truth about family tragedy

01 March 2019 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos LeeAnn Dance. Read time >10 min.

University of Cape Town (UCT) staffer Judy Favish’s father, Mannie Shamis, never talked about the past – abandonment by his mother, orphanhood or the pogroms, the organised massacres of East European Jews that followed the 1917 Russian Revolution and were a precursor to the Holocaust.

But his mother Feiga’s 40-page letter to her two children, who were sent from Warsaw as orphans to South Africa, has finally shed light on a family tragedy and the pogroms that decimated Jews in Eastern Europe, an area to which nearly 80% of the world’s Jewry can trace its roots. As many as 400 000 children were orphaned.

One hundred years later the story has inspired a new film. My Dear Children, by United States film-maker LeeAnn Dance, is the first in-depth, scholarly documentary on the pogroms. It is also a story about Mannie’s legacy: the values that were shaped by the hardships of the pogroms and passed on to his descendants.

Nominated for a Suncoast Regional Emmy, the film will be released in Cape Town on 26 March and in Johannesburg and Durban on 28 and 31 March respectively.

At its centre is Mannie’s daughter Favish, former head of UCT’s Institutional Planning Department and now a research associate in the School of Economics and a consultant in the Department of Higher Education and Training.

It follows her 2013 pilgrimage to trace her grandparents Feiga and Kalman Shamis’s route from Weber in the Ukraine to Warsaw in Poland, with their 12 children, as they sought to escape the pogroms that occurred between 1919 and 1921.

Diaspora of a family

Supported by additional footage from Russian archives, historical perspectives, research and material gleaned from UCT Libraries’ archives, the film tells a very personal story of a mother’s quest to save her children.

“The film has very powerful visual material about the pogroms which has never been seen before,” said Favish.

It also features UCT’s Professor Richard Mendelsohn, whose perspectives as a historian and author helped to bring these events “out of the shadow of the Holocaust” to audiences around the world, according to Dance.

Eventually, Feiga’s children were dispersed. Two were sent to New York, five survived only to die in World War II German concentration camps, and one ended up in Palestine. Mannie (8) and Rose (10) were brought to South Africa, thanks to Jewish benefactor Isaac Ochberg, a South African whose mission was to rescue 200 Jewish orphans from Eastern Europe after World War I.

With Prime Minister Jan Smuts’s permission to bring them into the country, Ochberg travelled by wagon through the Ukraine, Lithuania and Poland to search out the neediest. In the end he “sealifted” a group of 178 (“Ochberg’s Orphans”) to South Africa, where they were taken in by two Jewish orphanages in Cape Town and Johannesburg.

Mannie was later adopted but Rose eschewed opportunities in a new family, never giving up hope that her mother would come for her.

But she never did.

Favish said her father never spoke of his past.

“As he held Rose’s hand, he wondered what awful thing he had done that made his mother choose to send them away.”

Dance wrote in her blog: “He did remember standing on the boat that left Warsaw in 1920 at the beginning of the long journey to South Africa. As he held Rose’s hand, he wondered what awful thing he had done that made his mother choose to send them away. It was a choice he struggled to understand for many years and it is this choice we hope to explore in this film.”

Ochberg’s Orphans

The film also includes material from the UCT Libraries’ archive, valuable local input, through UCT retired Jewish Studies librarian Dr Veronica Belling.

“My involvement with the archival collection of Oranjia, the Cape Jewish Orphanage, began when I started receiving queries from descendants whose parents grew up in the orphanage that was established in 1911,” said Belling.

“Many queries came from the descendants of the Ochberg Orphans, the 178 children (like Favish’s father and aunt) who were rescued by the philanthropist Isaac Ochberg.”

Among the Oranjia collection’s 200 boxes are two that are devoted to the rescue of the children in 1920. These contain lists of the children’s names, as well as forms that were filled in for each of the children in Poland, added Belling.

“These forms recorded their names, where they were found and in what condition, their parents’ names, and most importantly, information as to how the parents met their deaths, either through sickness, particularly typhus, or murder in the pogroms that occurred in the Ukraine between 1919 and 1921.”

The lists of names are in Yiddish and English, but the forms are written only in Yiddish, a dying language that few can speak, read and write today, she said.

Fortunately, Belling had studied Yiddish on the Yivo Weinreich programme in New York.

“One of the things we found was the original certificate which Feiga signed authorising Ochberg to take the two children. They also found some armbands the kids wore to show they were part of the Ochberg group.”

Letter to my loves

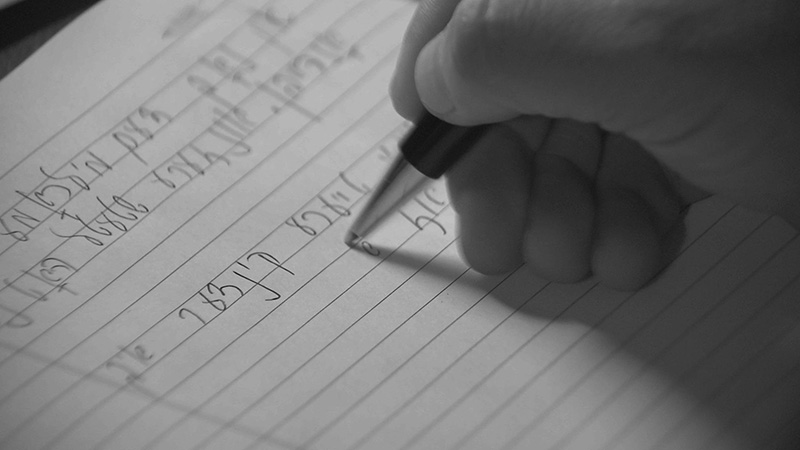

Though Feiga never came for her children, she stayed in touch with them. And years later when Mannie visited her in Palestine (she’d settled on a kibbutz with one of her children) while he was a soldier in North Africa during World War II, she gave him two copies of her handwritten 40-page letter in Yiddish.

“The letter was the story of her life.”

“The letter was the story of her life,” said Favish.

Unable to speak Yiddish, neither Mannie nor Rose could read the letter. Years later Mannie had it translated.

“But my father never read it,” said Favish.

“He couldn’t handle it. He wasn’t prepared to go there.”

After Mannie died, Favish’s mother had it properly translated and edited, and made into a small book, with copies for each family member.

Serendipitously, Dance came across a copy via her husband’s lung specialist in Washington, Favish’s first cousin. (“It’s a story filled with connections,” said Favish.) Dance was captivated and asked Favish if her film crew could accompany them on their journey.

The documentary came as a surprise, said Favish. What started out as a very personal trip became the cornerstone of the film.

“My personal quest was to try to understand how my father’s legacy had shaped him and why a mother would give up her children for adoption. Hers [Dance’s] was to try to contextualise that question.”

Road of remembrance

Favish was accompanied by her daughter Tess. Her son Kieran, a teacher, was unable to travel during term.

Their journey began at the orphanage in Warsaw where her father was when Ochberg arrived there. The film moves from the Old Town in Warsaw to L’vov in the Ukraine, ending in Kiev, where Favish’s grandfather, Kalman, had died of suspected cholera and tuberculosis in hospital. When Feiga returned to the hospital after sorting out the paperwork, his body had already been removed to the Jewish cemetery.

But when the mother and daughter visited the cemetery, there were the remains of only a few graves.

“In one area we found a few fragments of tombstones. That’s where we think Kalman may have been buried. But there’s no proof…”

Favish placed a symbolic stone on one of the headstones, as she did at all the cemeteries they visited.

“They were in such bad states it was impossible to identify individual graves.”

She’d known that she wouldn’t find any survivors, but she was shocked by how evidence of the Jewish people who’d once lived in the area had been completely erased.

“In Kiev, an open-air market had been built over the Jewish cemetery. In Kremenets, a bus station had replaced the synagogue. The synagogue where my grandparents were married had been converted into the local government office. The Jewish cemeteries were in a terrible condition. There was scant evidence anywhere of the Jewish communities that had lived and died there.”

Small miracle

But in Warsaw there was a small miracle.

On 51 Sliska Street they found the building that once housed the orphanage where Feiga had worked as a cleaner and where four of her children had been protected. It had survived the war. Today, it’s a children’s hospital, a small comfort.

The building represented an end and a beginning for Mannie and Rose.

“From there, they left for South Africa where they were spared the horrors of the concentration camps.”

Dance’s blog reads: “… from there, they left for South Africa where they were spared the horrors of the concentration camps two decades later.”

Favish is philosophical about what drove Feiga.

“She did what she had to do to ensure her children would survive. She sold vodka and who knows what else she had to do to... Her hardness was a defence against the violence, mass killings and rapes of women and children that she had witnessed every day.”

One of the scholars Favish met during filming in New York, who had made a study of violence perpetrated against women and children in periods of mass killings, said Feiga herself may have been raped, perhaps her children too.

“In writing this letter… as a woman she probably couldn’t talk about what had happened to her. Women of her era never spoke of such things.”

Historical gem

Nonetheless, in Feiga’s 40-page letter historians realise they have a gem.

“There are very few live accounts of the pogroms written from the perspective of a woman,” said Favish.

“That’s why the scholars who are interviewed in the film feel this is quite a special story.

“The more I understood about the period the more I was filled with admiration for this woman and how she managed to keep her family alive and get some of her kids to Warsaw and still do what she did to ensure they would have a chance in life.”

What has been lost and what gained? Favish’s answer is hesitant.

“I wanted to go; to try to understand why it had such a deep impact on my father and his values and how he operated in the world.”

“I wanted to go; to try to understand why it had such a deep impact on my father and his values and how he operated in the world. His sister [Rose] was the same in this: They were totally dedicated to their families. Both hated conflict, they were extremely gentle people who just wanted peace.

“He was dedicated to integrity and justice. I imbibed a whole lot of his values: fairness, commitment to social justice, and from my mother’s side, but my father was a man of absolute integrity who was totally against all forms of discrimination or persecution; people were entitled to their rights.”

From him she also learnt tolerance, and about human rights and social justice, and got unwavering support in the anti-apartheid struggle and when she was served with a banning order under the Internal Security Act in 1976.

“He was amazing because he understood what it was like to experience oppression. In South Africa that was race. So that’s how I grew up – opposed to any form of discrimination, persecution, oppression.”

“Histories of pogroms should be recorded so that people don’t forget what has happened – or sadly is happening even now – so that people are galvanised to act in solidarity with oppressed people to end their oppression.”

Jews have a special responsibility

Favish believes that because of their history Jews have a special responsibility in this regard.

“We need to find political solutions to the conflict in Israel and Palestine so that all people in the area are able to exercise their fundamental human rights associated with a democracy.”

These values have been passed on to her own children.

“So, there is this kind of legacy.”

Her loss is in the silence.

“I wish my father had been alive to talk about this. But I’ve gained key insight into him as a person, into my aunt as a person, our history and the effects of our legacy. That’s certainly helped us as we continue to live our lives. We take all of that with us and we try to ensure that the next generation will remember what happened.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.