South Africa is in trouble – here’s how to fix it

17 July 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Read time 9 min.South Africa is in trouble. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the economy was already in a recession. The expanded unemployment rate was at a frightening 42% and expected to reach 50% by the end of the year. The country remains one of the most unequal societies in the world and the scourge of sexual and gender-based violence continues to plague communities.

An already troubling situation has been compounded by the pandemic and the reality of South Africa’s “two-speed society” cannot be ignored. One part is modern, affluent, technologically advanced, skilled, mobile, dynamic and increasingly non-racial. The other is jobless, marginalised, unskilled, young, mostly rural or peri-urban outcasts, largely black South African, and increasingly restless, bereft of hope and condemned to poverty.

These are the hard truths presented by Colin Coleman, a senior fellow and lecturer at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs, a senior advisor to the Eurasia Group, and a non-executive member of the board of The Foschini Group.

Coleman was delivering the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) first Vice-Chancellor’s (VC) Open Lecture for 2020. His lecture was titled “From a ‘two-speed society’ to one that works for all – Doing ‘whatever it takes’: A 10-point action plan to grow an inclusive South African economy and escape a socioeconomic crisis”.

The lecture took place on Wednesday, 15 July, and was the first time that a VC’s Open Lecture was hosted online. Audience members included prominent names such as former finance minister Nhlanhla Nene, Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan, the former statistician-general of South Africa Pali Lehohla, UCT Chancellor Precious Moloi-Motsepe and the new UCT Council chairperson, Babalwa Ngonyama.

A fiscally neutral basic income grant

While Coleman painted a very real and grim picture of the situation in South Africa, the focus of his lecture was to propose a 10-point action plan to forge “one economy that works for all”.

Briefly, the objectives of the plan are to collect as much tax revenue as the economy can digest; to make every cent of expenditures count; to take people out of starvation and hunger; to wage war on corrupt, wasteful and irregular expenditure; to provide jobs and opportunities; and to be ruthless in prioritising spending in the interests of economic justice for all South Africans.

“This is an economy that should shield the poor from poverty, grow at 5% per annum and add five million jobs by 2030,” said Coleman.

The first point is to introduce a fiscally neutral basic income grant (BIG). According to Coleman, it is essential that, as an emergency measure, a universal and comprehensive solution in the form of targeted basic income support is provided.

Having applied the International Poverty Line benchmark of US$2.00 per day – which is equivalent to roughly R1 080 per month across 10.8 million people – Coleman established that the proposed BIG would cost South Africa around R140 billion per annum, before annual inflation.

His proposal would be to introduce the BIG, effective from October 2020 when the temporary COVID-19 grants terminate, and by targeting the 10.8 million unemployed South Africans. Coleman also presented alternatives for the R140 billion, one of which is to target all 32 million adults with R365 per month, with a clawback for those above an income limit. The other is to target all 23.4 million labour force participants with R500 per month, also with a clawback.

“The merits of the alternatives should be subjected to a rigorous review,” he said.

“The key criteria should be maximising economic impact on poor households, simplicity and cost of administration, and speed and effectiveness of getting cash into the hands of the targeted beneficiaries.”

Reforms, waging war, rescuing business

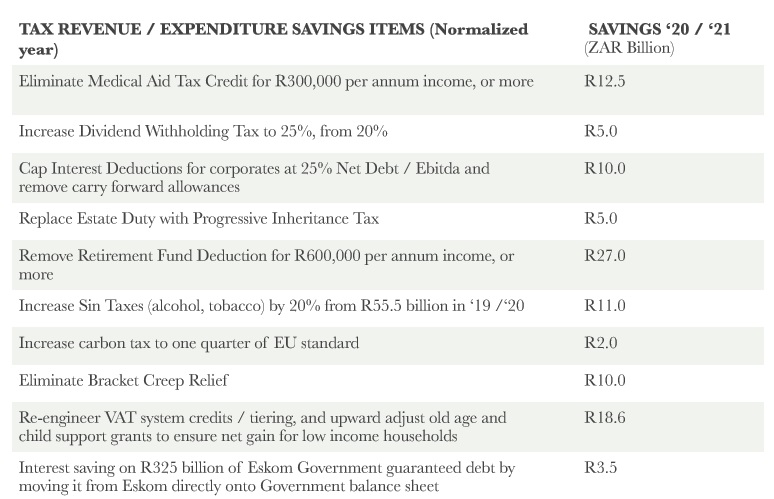

The second point is to introduce tax reforms to fund the BIG. This point, which Coleman has previewed with some of the country’s leading tax experts, aims to re-engineer the application of existing tax revenues and allocations, thereby making the BIG possible in a fiscally neutral manner.

“Such a BIG should not only be seen as an expenditure, [but also as] an investment and may represent the best form of short-term economic stimulus this country could now introduce, particularly in this COVID-19 crisis moment,” said Coleman.

He explained that as the BIG recipients are likely to spend the grant on essentials such as food and clothing, the immediate benefits would be felt across the economy, including in VAT payments and increased corporate tax.

“This will be good for confidence, national unity and solidarity, and enhancing the economy and society,” he said.

The point is to wage war on the illegal economy. This includes tax reforms that focus on tax compliance and enforcement, encouraging all South Africans to support the South African Revenue Service, and state enforcement agencies clamping down on the rampant illegal and unrecorded economy.

Coleman’s fourth point is providing urgent relief to businesses. The focus would be on troubled but normally solid businesses and would involve reimagining the remaining yet unallocated R100 billion of the president’s R500 billion COVID-19 package in the form of interest-free loans via participating banks.

His fifth point is, in short, about assisting small, medium and micro enterprises by improving the ease of doing business and removing obstacles in their way.

“A pact to buy local, build local and employ local, not to the exclusion of others, should guide everyone,” said Coleman.

‘The time is now’

In his sixth point, Coleman discussed unlocking infrastructure projects while in his seventh, he calls for the creation of an e-government platform to modernise the public sector.

Point eight is the mammoth task of fixing Eskom.

“Fix Eskom’s balance sheet once and for all.”

Among his proposals for the state-owned enterprise, Coleman advises moving all Eskom-guaranteed debt to the government balance sheet on negotiated and enhanced terms with bondholders, thereby capturing the benefit of the over 1% annual credit spread saving. Currently, this is equivalent to R3.5 billion per annum between the government and Eskom’s cost of borrowing.

“Such a move is credit-neutral for the sovereign as the credit rating agencies have already written up the contingent liabilities into their sovereign debt models,” he said.

Coleman’s ninth point is to review and redesign South Africa’s industrialisation architecture and aims to increase the country’s support for industry, manufacturing and mining.

“In the next decade, South Africa needs to ask itself how we can create five million jobs, twice the job creation rate of the last decade, to bring down the formal unemployment rate, at least to below 20%, if not lower,” he said.

“Now is not the time for timidity.”

The final point is ending apartheid spatial planning. This, Coleman said, can be done by targeting densified, integrated urban settlements.

“The human, social and economic cost of segregated and remote townships and informal settlements [are] both unacceptable and unaffordable,” he said.

Coleman said that the release of land and the densification thereof with integrated human urban settlements is “probably the largest untapped economic and infrastructure opportunity of our time”. It would require a massive government-led effort, bringing together urban planning experts, construction companies, civil society and all relevant stakeholders.

In closing, Coleman stated that “now is not the time for timidity”.

“The time is now to bridge the divides, to wrap our arms around our fellow South Africans who are destitute, starving and jobless. The 10-point plan is a comprehensive proposal to turn the tide towards economic inclusion and dynamism.

“It won't be easy. But we can do it!”

- Read Colin Coleman’s full speech.

- Read the executive summary of Colin Coleman’s speech.

- Read the fact sheet on Colin Coleman’s “ten-point action plan”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.