Heritage Month: UCT cleansing ceremonies a powerful transformation narrative

29 September 2021 | Story Helen Swingler. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 10 min.

The University of Cape Town (UCT) marked an important milestone in its transformation journey when Khoi and San land cleansing ceremonies were held at three locales on its Rondebosch campuses. The ceremonies are part of UCT’s Heritage Month activities.

They were led by Tauriq Jenkins, the chair of the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum, and B’ia Bradley van Sitters. The rituals are an important part of the Khoi and San spiritual heritage, with a restorative significance at UCT.

UCT’s main campus on the back slopes of Table Mountain, or Huri ǂoaxa (Hoerikwaggo, which means “the mountain in the sea”), occupies land that was once home to Khoi and San peoples who were persecuted by early colonial settlers, driven off the land and severely marginalised.

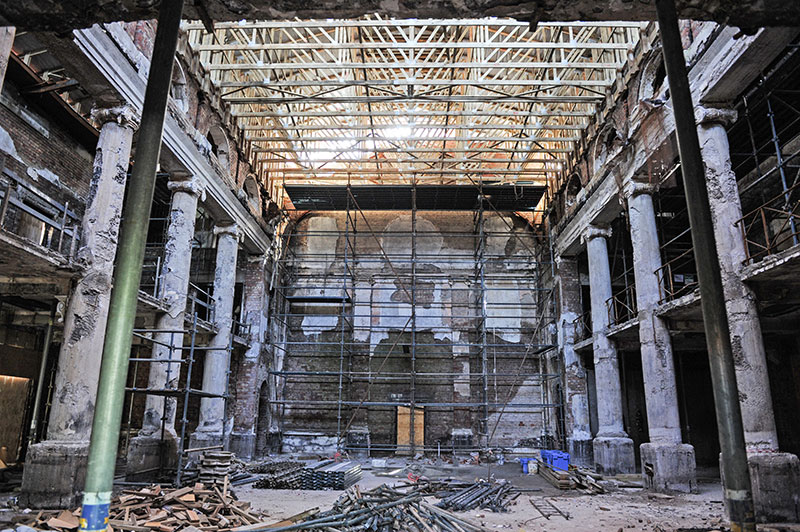

A video of the ceremonies is included in the 29 September Faculty of Humanities San & Khoi Heritage Month Colloquium, “Unburning the Fire” and the Acknowledgement of Land Cleansing ceremony. The significance of “Unburning the Fire” relates to the destruction of the Jagger Reading Room (formerly the JW Jagger Library) in the Table Mountain fire on 18 April 2021. The Jagger Reading Room was home to the significant African Studies Collection, started in 1953.

Reawakening dignity

Khoi and San cleansing ceremonies involve lifting of the (eland) horns and burning impepho, a dried indigenous African plant that the Khoi and San traditionally burn to communicate with their ancestors.

“It’s an acknowledgment of the ancestors, the reawakening of dignity, a connection with the silenced narrative of people whose histories we are celebrating,” said Jenkins, who is also the community engagement strategist for the San and Khoi Centre. His traditional title is High Commissioner of the Goringhaicona Khoi Khoin Traditional Council.

“[These] rituals are also the ones that invocate the ancestors, so very important names are chanted, and the chants are in every direction, from north, east, south and west, as if to summon and also ensure that there is a cyclical component in terms of the rhythm and how the leaders are connecting within the space.”

Working with the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum and Khoi and San leaders, UCT has introduced several initiatives to restore their language, culture and history. The first was a Khoekhoegowab online language short course, launched in 2019 and the first of its kind for a South African university.

The second was the Khoi and San Centre in the Centre for African Studies, which foregrounds erased or marginalised indigenous knowledge, rituals, language and “ways of knowing” of the San and Khoi clans.

The third was renaming Jameson Memorial Hall to Sarah Baartman Hall, a Khoi woman who was captured and paraded as a curiosity in the United Kingdom before her dismembered remains were repatriated to South Africa centuries later.

Jenkins described the cleansing ceremonies as a “trail of tears”.

The group began near Kramer Law Building on middle campus, locale of the Rustenburg Remains; the human remains of Khoi and San slaves who once worked the lands of the former Rustenburg Farm situated here and discovered during building excavations.

“This is a significant and largely unrecognised epicentre of a history that, in many ways, has not been publicly profiled,” said Jenkins.

The Khoi and San communities hope to have a plaque erected here to commemorate what is still an unmarked grave, he noted.

“Although the Rhodes statue is no longer there, it continues to be a place of dialogue.”

“We hope that students will [learn] about the Rustenburg place and become curious to know that these are sacred terrains; sacred spaces.”

The group then moved to upper campus, performing a cleansing ceremony at the Cecil John Rhodes plinth.

“Although the Rhodes statue is no longer there, it continues to be a place of dialogue,” said Jenkins. The cleansing ceremony acknowledged the trauma of students (Fallists) who fought for the statue’s removal in 2015 and played an extraordinary role in changing the face and pace of transformation at UCT.

“Once [the statue of] Rhodes had fallen, we would find that a domino effect also impacted across campus, and for the San and Khoi communities in the A/Xarra Restorative Justice Forum, Sarah Baartman is an epitome of these very powerful, transformative steps that have been taken by the university in conjunction with the community.”

The Fallists had also been part of a history of liberation and resistance that had begun as far back as 1510, he said.

“On 1 March 1510, on the banks of the Liesbeeck River, the Portuguese were defeated by the Khoikhoi. And then again, in 1659, when the first frontier wars were fought, just down the road in Observatory, the Dutch East India Company – after having gifted farms to the free burghers – took the territories of the indigenous communities.

“And as a result, a war broke out and that resulted in 180 years of liberation resistance by the San and Khoi, which fanned out through the course of 16 wars and resulted in the genocide of the Cape San and the ... forced removal of communities. It was a wave of dispossession and forced migration, which emanated from the epicentre here in the Western Cape, right the way through to Botswana, Namibia, Angola.”

Last, the group moved up to the Sarah Baartman Hall and the remains of the Jagger Reading Room.

At the Sarah Baartman Hall, Jenkins said, “It’s tremendously beautiful when you see that name. I think any student who graduates within the heart and the spirit of Sarah Baartman is also graduating into the depth of South Africa’s past and the depth of our future as a unified and courageous country; [one] that can take a figure like Sarah Baartman, who was disfigured in the most literal and visceral way and who, in many ways, is symbolic of the scramble for Africa … but now … reconnected [to the land] and sitting on the hill, has tremendous resonance.”

Deeper reality and history

But the land cleansing ceremonies reached much deeper, said Jenkins, and are part of a restorative programme and a process of social justice and of articulating this part of history in a different way.

“Acknowledging the San and Khoi footprint also opens up a powerful narrative of belonging for communities in the Western Cape.”

“Acknowledging the San and Khoi footprint also opens up a powerful narrative of belonging for communities in the Western Cape and around this country; a powerful narrative for those communities to also return home and to acknowledge those parts of ourselves as communities that have resonated so much with shame and that have alienated us in many ways.”

Having these kinds of events, he added, is very much about the “unburning” of the library and the kinds of things that can be done to find redress and acknowledge in deeper ways the loss of knowledge in the library.

“[It’s] not so much cordoning off or silencing and cornering this episode … but bringing it to the fore and knowing that it’s part of our history, and we should be actively pushing for a full lens of restorative justice, and full openness in terms of how we accept who we are as South Africans, and how we connect this campus to that past in ways that is respectable and dignified.

“Today … the ritual is returning to campus. And this has been part of a process that has been ongoing since the reintroduction of Khoekhoegowab, which is the Khoi language, by the university. And this move has prompted several linguistic and cultural and spiritual and sacred events and practices on campus. For example, the repatriation of the sacred human remains from the human biology department [to Sutherland]. These processes have to be conducted in ways that are also in sync and respectful to the spiritual and indigenous practices of communities here.”

“But as Sarah Baartman has metaphorically also risen from the ashes, so is the optimism that rises out of the ashes of that library.”

Finally, the group acknowledged the tragedy of the fire damage to the African Studies Collection, a particularly painful episode for the Khoi and San too.

“This is the first time that members of the community have been able to engage with the trauma of the burning of the library,” said Jenkins. “It held an incredible reservoir of knowledge that is particular to us as Africans, and its burning meant a devastating erasure of knowledge [compounding] the already existing problem of linguicide and ethnocide; the historical erasure of marginalised groups in this country.”

Jenkins said the magnitude of the loss had prompted the community to consider performing another, more focused cleansing ceremony at site of the burning.

“But as Sarah Baartman has metaphorically also risen from the ashes, so is the optimism that rises out of the ashes of that library.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.