University of Fort Hare – a tale of academic freedom and institutional autonomy

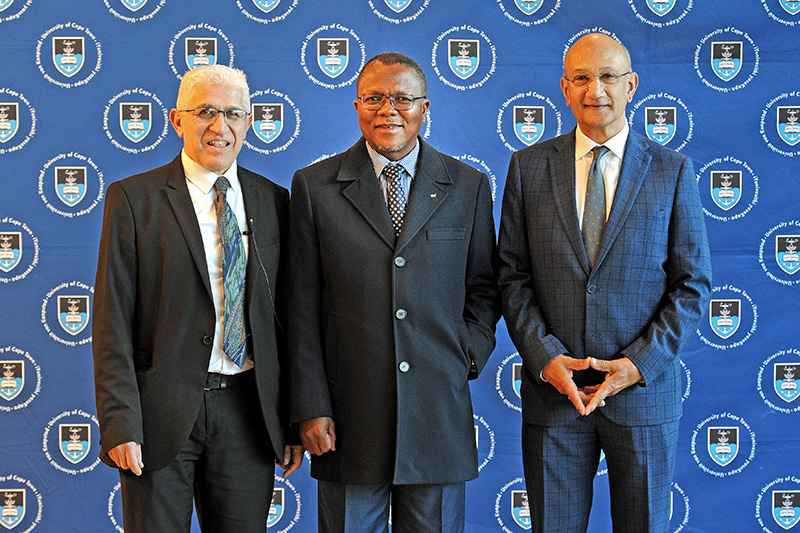

25 August 2023 | Story Niémah Davids. Photos Lerato Maduna. Director Nico Badenhuizen and Ruairi Abrahams. Videography and Video Edit Ruairi Abrahams. Read time 9 min.When they say the legacy of apartheid remains deeply rooted in the fabric of South Africa’s multiracial society, believe them. Three decades into a democratic dispensation and the University of Fort Hare (UFH) continues to reel from a “hostile 1950s takeover” strongarmed by the National Party. The effects have left a trail of destruction and severely threatened academic freedom and institutional autonomy.

This was Professor Sakhela Buhlungu’s poignant message as he reflected on the “captured” institution during the annual University of Cape Town (UCT) TB Davie Memorial Lecture. Professor Buhlungu is the vice-chancellor (VC) of UFH and the former dean of UCT’s Faculty of Humanities. His speech was titled: “Academic Freedom and Institutional Autonomy: A View from the Tyhume Valley”.

The lecture is hosted annually by UCT’s Academic Freedom Committee and honours the memory of former UCT VC Thomas Benjamin Davie – a fierce defender of the principles of academic freedom. He died in 1955. Significantly, Buhlungu is the second UFH academic to deliver the lecture. In 1961, political activist and former acting UFH VC, Professor Zachariah Keodirelang (ZK) Matthews, presented the third TB Davie Memorial lecture, which was titled: “African Awakening and the Universities”. The lecture also made the link between academic freedom and the quest for liberation in South Africa and on the continent.

Assault on academic freedom

More than six decades later and it was Buhlungu’s turn to take to the podium. His lecture identified four moments that marked the introduction of ethnic education and assault on academic freedom at UFH, which have had a debilitating effect on the university, and which the current administration still contends with today.

The loss of autonomy, he said, started in 1959 when the National Party passed the University College of Fort Hare Transfer Act, which set very strict parameters. The institution was ordered to cater strictly for Xhosa-speaking students and enforced segregated governance and administrative functions. This included creating a separate council and senate for black people. Professor Johannes Jurgens was appointed as the institution’s new VC and his role was to oversee the transition of “turning the university into an apartheid instrument”.

“And so began a process of taming Fort Hare; of domesticating Fort Hare; of tribalising Fort Hare.”

“And so began a process of taming Fort Hare; of domesticating Fort Hare; of tribalising Fort Hare,” he said. “The Transfer Act was brutal. There was no room for negotiation or bargaining. White English staff [members’ contracts] were terminated and black staff were given the option to exit [the university]. And that period marked the first major assault on academic freedom and institutional autonomy at Fort Hare.”

‘A heavy-handed oppression’

And the takeover continued into the 1960s. In 1968, when Professor Johannes de Wet was appointed as the institution’s new rector, Buhlungu said his arrival ushered in a new era of heavy-handed oppression. Professor De Wet was a member of the Broederbond – an exclusively Afrikaner Calvinist and male secret society dedicated to the advancement of the Afrikaner people. He was on a mission to intensify state control of the university.

Buhlungu said De Wet’s arrival sparked mass student protests over fear that he was an instrument of the apartheid government. And even though he initiated and completed several university infrastructure projects, including building a library and various teaching and administrative buildings, he was not welcome.

“The De Wet administration played a huge role in limiting academic freedom and reconciling the institution to the state and its apartheid ideology. Not only did he curtail students’ freedom of political association and expression, he also ensured that staff who opposed apartheid were not allowed to be active on campus,” Buhlungu said.

De Wet also banned the National Union of South African Students and ensured that the police had open access to campus. When he left, Buhlungu said, the university had completely lost its autonomy.

Hostile takeover

But according to Buhlungu, the assault on academic freedom and institutional autonomy didn’t stop with staff and students. It was also directed at the Federal Theological Seminary of Southern Africa (Fedsem) – a multi denominational institution located adjacent to the UFH campus. In 1974, Fedsem was expropriated, and forcefully annexed to UFH in 1975. Today, he said, the seminary and its chapel forms part of the university’s east campus.

But the 1970s were significant for a number of other reasons too. The Bantustans were offered first option of independence from South Africa, and the first to opt for this independence, he said, was the Transkei in 1976. Five years later, when the Ciskei was granted independent status, UFH was handed over. But the management remained firmly under white control. By then, Buhlungu added, academic freedom had become a sham and institutional autonomy was non-existent. In response, he said, many students joined internal movements or fled to join exile movements like the Black Consciousness Movement, the Pan Africanist Congress and the African National Congress.

“The University of Fort Hare was a shadow of its former self,” he said.

By the end of the 1980s, dismantling apartheid and building a free, democratic South Africa was the number one goal. Yet, after the first democratic election in 1994, university administrators faced frequent and often violent staff protests, which, he added, caused instability at the institution.

A poisoned chalice?

Buhlungu joined a fragile UFH in February 2017 before he completed his fixed term five-year contract at UCT, and it’s been a rocky road at the helm.

“Often people ask me, had I known what awaited me at Fort Hare, would I have taken the job as VC? I still do not have an answer to that question. Indeed, I often ask myself: Did I accept a poisoned chalice at UFH? Again, I have not formulated an answer yet,” he said.

His entry into the university was marred by protest action that crippled the teaching and learning project for several weeks. Add resource constraints to the mix and it’s a recipe for disaster. But that was more than six years ago – what threatens academic freedom and institutional autonomy today? Buhlungu said the heavy burden of bureaucratic micromanagement that involves regularly sending copious reports to government can be regarded as an attack on institutional autonomy. Added to that, he said, physical violence perpetuated against UFH staff also poses a threat to academic freedom. And in the past two years, two UFH staff members, Petrus Roets and Mboneli Vesele, have been murdered. Do these gruesome acts threaten freedom of expression and academic freedom?

“Autonomy has been eroded so much that these syndicates are so confident [and] so brazen that they now kill. They don’t just send memorandums, [cause] unrests or protest, they now kill. And that’s where we are now,” he said. “Where we are, we are now battling the syndicates in [a] very real sense. We are battling them with ideas, with words; they’re battling us with guns.”

Academic freedom today

In the context of academic freedom today, Buhlungu argued that it means different things for different institutions. And these, he added, are shaped by different histories and sociopolitical contexts.

“We should move away from this homogenised [idea] that there’s one definition of academic freedom for everybody.”

“We should move away from this homogenised [idea] that there’s one definition of academic freedom for everybody. No, it means different things. It’s shaped by our different histories. We [UFH] come from a particular history that has kind of killed the soul, the fibre of our institution since 1959 and the roots of the violence and the killings and what you see on TV today, it originates from there,” he said. “So, let’s be mindful and open up this notion of academic freedom and autonomy because they’re different.”

Similarly, he also reminded the audience that striving for academic freedom and institutional autonomy in one university alone is meaningless.

“If we continue to have these kinds of debates about academic freedom that don’t look at the big picture … The picture being not just in the province of the Western Cape or the Eastern Cape, not in South Africa, but globally. That’s the only way we can get to really meaningful and constructive and successful debates about academic freedom.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.