The ‘two faces’ of UCT

07 February 2020 | Story Niémah Davids. Photos Je’nine May. Read time 7 min.

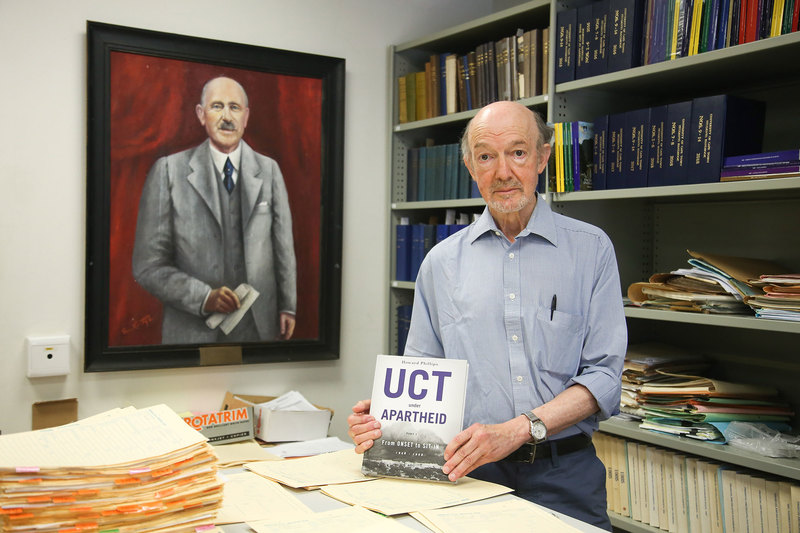

When the University of Cape Town (UCT) commissioned historian and retired academic Emeritus Professor Howard Phillips to author the book UCT Under Apartheid: Part 1 – From onset to sit-in – 1948–1968, he was unprepared for what awaited him at the university’s archives.

It was the “two faces” of UCT during this period that surprised him.

To the public, UCT had always portrayed itself as a so-called “open university” during the height of apartheid South Africa. But how “open” was the institution really?

“On the one hand, UCT’s public stance regarding apartheid was strongly against what was widely termed ‘university apartheid’. [This referred to] the restriction of who it [the university] could admit, the restriction of who could teach, and the restriction of what could be taught,” Phillips explained.

“UCT in public set its face very much against all of those [restrictions] and there were big demonstrations against university apartheid.”

But the practices that unfolded on campus during that time painted a different picture.

Racial discrimination

While conducting his research, Phillips discovered that UCT had enforced a number of racially discriminatory measures on campus, and university authorities required that students abide by those rules.

“Black students were not allowed to view a white body, and so if the patient to be demonstrated was white, black students had to leave the room.”

For instance, he said, black medical students were not permitted to enter white wards at Groote Schuur Hospital, or examine white patients. Neither were they allowed to attend a post-mortem on a white corpse.

“Black students were not allowed to view a white body, and so if a patient to be demonstrated was white, black students had to leave the room,” he said.

In addition, at the Michaelis School of Fine Art, which “you might think is a thousand miles away from anything political”, until the 1960s black students drawing from life were not permitted to draw a white model.

“[Black students] had to go to a separate room to draw a black model,” Phillips said.

“In a range of ways, when one began to look under the surface of UCT’s public stance on apartheid, there’s another story to be told, which is not flattering to UCT.”

UCT in transition

The book also depicts several positives over the 20-year period.

One of them, Phillips said, refers to the transition from a solely teaching-focused institution, to one that incorporates a research-led component as well. By 1968 research had already joined teaching as a significant activity at UCT.

“Today, UCT prides itself as being a research-driven university – that doesn’t come from nowhere. You can actually see that beginning to happen in the period covered by the book,” he said.

In the 1950s and 1960s, he said UCT researchers were also in the forefront internationally in fields like heart surgery, nutritional deficiency, oceanography and marine biology.

Phillips maintained that to understand the present, it’s necessary to unpack and understand the past first, which is what his book seeks to do.

“The book allows for the present and its historical baggage to be better understood, and for the future to be better mapped out.”

Yes, readers might question the book’s relevance when the country and the world have undergone significant changes since the period under review, but for Phillips it provides a “series of important perspectives”.

“If the present is research-led, how did it come about? If the present is trying to decolonise the curriculum, how did that come about? Or if the present is looking at how the university should come to terms with its apartheid past, what happened during the apartheid era [at UCT]?”

The book in brief

Phillips explained that the book, like others of its kind, uses an introduction and conclusion to paint a clear picture of the university at the start of 1948 and then again at the end of 1968.

The chapters in between cover the UCT administration, construction and buildings, and a series of chapters on the academic project, which include teaching and learning and research.

“I’ve also tried to weave in students’ experiences and their perspectives of what it was like to be taught. So, it’s not just about the teachers, but also about those who were taught and their views,” he said.

“UCT also has a side of its history which isn’t that admirable, and we need to take that on-board.”

More than that, and because UCT “doesn’t exist in a vacuum”, Phillips said he included a chapter on what he calls “reaching out”. This refers to UCT in a broader context and extends beyond the university’s doors and explores its relationship with the wider Cape Town community.

Another chapter, and probably one of the book’s most significant sections according to Phillips, is UCT’s “mixed relationship” with the apartheid state – “Colliding and colluding”. It attempts to capture the rules and decision-making processes of that time, as well as the mindsets of UCT authorities.

“UCT opposed, resisted and stood up against apartheid, but UCT also has a side of its history which isn’t that admirable, and we need to take that on-board. This book helps us do that and understand why, as a university, it behaved in this way,” he said.

‘History in the round’

To those non-historians reading this, Phillips explained his approach to writing the book as “history in the round”.

In partnership with his research assistants, Ms Lesley Hart, Dr Farieda Khan and Dr Neil Overy, Phillips conducted almost 200 interviews with former staff and students at UCT, examined 25 years of editions of the student newspaper, Varsity, and roughly 50 000 photographs and cartoons. Letters and correspondence by individuals linked to the institution at the time also formed part of his information-gathering process.

“This book doesn’t survey just one angle, instead it’s a perspective from 360 degrees,” he said.

Phillips credits UCT’s “rich” archives and Special Collections, a division of UCT Libraries, for being a “treasure box of UCT’s history”, the librarians there, and archivists, Lionel Smidt and Stephen Herandien, for their role in making readily accessible material for the book.

“This [UCT archives] is a little-known treasure trove. We’re sitting here on 190 years of intellectual history of sub-Saharan Africa. I’ve been immensely privileged to have access to it and to have been guided by two such knowledgeable and willing archivists,” he said.

“The book allows for the present and its historical baggage to be better understood, and for the future to be better mapped out.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.