Human waste on world innovation stage

27 February 2020 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Robyn Walker. Read time 7 min.

“There has to be a better way of doing this civilisation thing,” University of Cape Town (UCT) master’s candidate Vukheta Mukhari said when he pitched his research at the 25th Design Indaba on Wednesday, 26 February. That research is revolutionising the way society sees human waste.

The design and innovation festival is on at the Artscape Theatre Centre until Friday, 28 February. Mukhari is one of the young global graduates selected to present their ideas at the Think Tank, handpicked together with the heads of over 40 design institutes and colleges around the world.

Each young innovator works at the nexus of academia and the green economy, and the selection criteria centred on the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Each is involved in highly innovative research that tackles global challenges and has social or environmental impact. And it’s translatable in the real world.

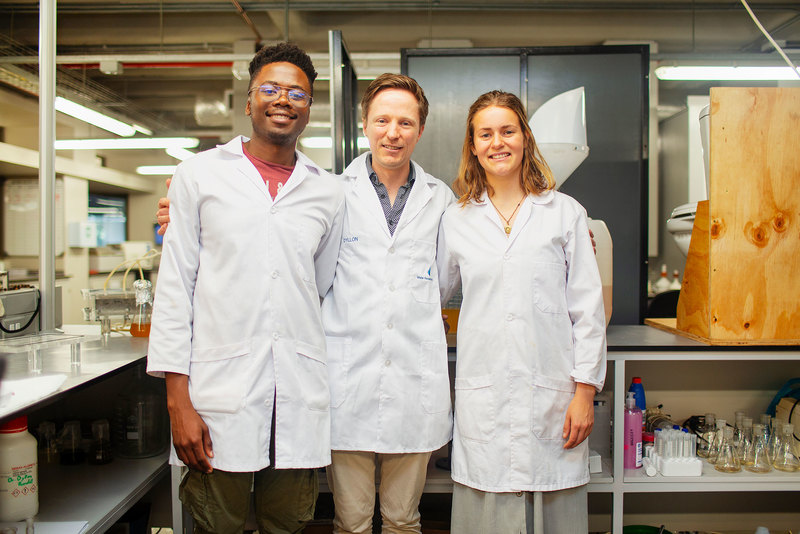

“Vukheta was chosen as one of only 12 candidates from around the world to speak at this event, so it’s quite an achievement. It is also fantastic that the organisers specifically contacted us to learn more about our urine bio-brick process,” said his supervisor, Dr Dyllon Randall.

On stage on the first day, Mukhari had just 10 minutes to describe how pee and pathogens had created a gamechanger in sustainable construction and human waste sectors. This is thanks to some intricate chemistry between urine and bacteria ─ a natural process called microbial carbonate precipitation. This creates bio-bricks from human urine, collected from waterless urinals. The by-product is fertiliser.

The bio-bricks were developed by Mukhari and master’s student Suzanne Lambert of the Department of Civil Engineering, working under Randall. The bio-bricks were unveiled at UCT in 2018 to huge acclaim, signalling a paradigm shift in the way society views human waste.

Biomimicry a design template

Continuing the theme of waste and sustainability, Mukhari told his audience that while civilisation had made huge strides to emerge from “a cave into the four-walls-with-a-roof and more food than we can eat”, the planet was imploding.

Biomimicry would provide a template for restoration and future design that worked with nature and ecosystems to inspire innovation and solve complex human problems.

Quoting biomimicry pioneer and biologist, Janine Benyus, he said, “Humans need to remember we are not the first to build structures, to master fluid dynamics or harvest moisture from the air and make things waterproof. Nature discovered all this long before we did and there are still so many discoveries to be made. We have only scratched the surface.”

And UCT was leading the way. He described how Randall and his students had uncovered something extraordinary.

“We grew the world’s first bio-brick made from human urine with the help of Sporosarcina pasteurii bacteria.”

“We grew the world’s first bio-brick made from human urine with the help of Sporosarcina pasteurii bacteria. My supervisor calls them Steve. We took some sand and aggregate, mixed it with bacteria, sealed it in a mould … and pumped urine through it.

“The bacteria break down the urea in the urine, which releases carbonate ions in a calcium-rich environment. This forms calcium carbonate, or calcite. This is the same calcium carbonate that nature uses to form seashells. The calcite naturally cements the sand particles together to form a bio-solid.”

Since then the team has been working to improve the bio-brick’s compressive strength. In three years, they’ve improved that exponentially from 0.9 MPa to 16 MPa, equivalent to the strength of clay bricks.

To market, to market

“Part of our current research is to optimise and refine the bio-brick so that it can be taken to market,” said Mukhari, pointing to unprecedented urbanisation worldwide. “This is important as the construction industry is responsible for consuming 40% of the planet’s energy and 12% of water, producing one-third of the carbon emissions and 40% of the waste.”

Sustainability is key. Clay and concrete bricks require large amounts of energy whereas bio-bricks are made at room temperature and created by recycling “waste” material through a natural cementation process.

And that’s not all.

In tandem with the project is a call for waterless urinals to collect urine and produce a no-energy phosphate fertiliser as a by-product. This is facilitated by a chemical additive which also prevents the ammonia smell, kills pathogens and helps degrade pharmaceuticals present in human urine.

“It’s actually groundbreaking … it’s liquid gold, a pee revolution.”

“Urine accounts for only 1% of municipal wastewater but contains 60 to 80% of all the nutrients contained in that waste,” said Mukhari. “By removing urine from the sewerage line, we’re effectively saving the treatment plant 60 to 80% money and energy. It’s actually groundbreaking … it’s liquid gold, a pee revolution.”

“This is an example of how we make use and reuse instead of making and then disposing. Nature knows no waste; what we call waste become a valuable resource.”

The real star, he said, is the collective Steve: the bacteria. And they can do so much more.

“They’ve cemented loose sand particles together, and we can apply that concept to other material, such as plastic waste, crushed glass and even concrete rubble to form sustainable construction material.

“The possibilities are legion: the process can cement material together to make clothing, furniture and food packaging.”

Mind blowing

Presenting on the Design Indaba platform is an experience Mukhari won’t forget.

“It was mind blowing hearing some of the best design ideas and solutions from all over the world which have a tangible impact for the communities they’re designed for. Being in that space feels like electricity running through the body – and in a good way!

“Creating networks is the best part; the indaba facilitates this so well. We get to mingle with the likes of the creative directors of Google and researchers using seaweed to green the construction industry. It’s amazing. There are already a few potential avenues of collaboration, which is exciting.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.