Research, exhibit exiled artists’ work lest they become ‘intellectual refugees’

22 February 2022 | Story Helen Swingler. Photo Gallo Images. Voice Cwenga Koyana Read time 8 min.

South African artists who went into exile during the apartheid years risk becoming “intellectual refugees” if institutions such as universities don’t step up to ensure their work is archived and researched – and this knowledge made easily accessible.

This appeal came from author and community activist Aubrey Mogase, a participant in the first of the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) online Conversation Series about the life and works of District Six-born photographer George Hallett (1948–2020).

Hallett went into exile in the United Kingdom in 1970, returning to South Africa only after Nelson Mandela’s release. He photographed the country’s first democratic election at the invitation of the African National Congress, as well as proceedings at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Instituted by the UCT’s Works of Art Committee (WOAC), chaired by Associate Professor Nomusa Makhubu (art history), the series is intended to bring Hallett’s work into broader focus. It is coordinated by Iziko Museum’s Ingrid Masondo, photographer, curator and project manager in the arts and heritage sectors, and curator of contemporary art Tšhegofatšo Mabaso, and will bookend the WOAC exhibition of Hallett’s work, which they are curating.

The first discussion was hosted by Dr Valmont Layne of the University of the Western Cape (Centre for Humanities Research) with guests Eugene Skeef, a musician, artist and poet, and painter and poet Lefifi Tladi.

Both were members of the Black Consciousness Movement and artists in exile. Skeef now lives and works in London and Tladi in Stockholm.

UCT has approximately 1 700 visual artworks in its collection, spread across 70 campus buildings. The series is part of WOAC’s mandate to oversee the display and integration of this art into campus life and to redress past injustices by purchasing work by prominent and emerging artists in South Africa. It re-curates how artwork is displayed across campus and makes sure that it reflects the diversity of UCT’s community.

Tell the stories

The task is urgent, said Mogase, before the work of artists in exile and those that followed pass into obscurity.

“Failure to tell our stories [means] we risk becoming intellectual refugees. We are lagging … How long has [photographer] Ernest Cole been gone? Yet, even today people from his hometown of Mamelodi don’t know him.”

“[But] before we talk about museums, we need to do the research. Our educational institutions need to step up.”

Universities have the resources to preserve and research this work, making it part of the country’s visual vocabulary, he noted. However, these institutions often place “invisible boundaries” to accessibility. This must be addressed.

“The range of Hallett’s work is very complex and substantial. [But] before we talk about museums, we need to do the research. Our educational institutions need to step up. Our students need to focus their research on the nation’s artists and place them into a discourse.”

Masondo added: “We have to be serious about developing, supporting and caring for archival resources.”

Raising awareness

The Conversation Series is intended to raise awareness of Hallett and his work, some of which was recently bought by the WOAC.

“These forums are important in catalysing conversations about and preserving the heritage we have … and opening this heritage to the public,” said Associate Professor Makhubu.

The focus on Hallett sits squarely in line with Makhubu and the committee’s thinking and plans for WOAC’s collection, its role in reshaping UCT’s art collection and transforming it into a resource for researchers, curators and students.

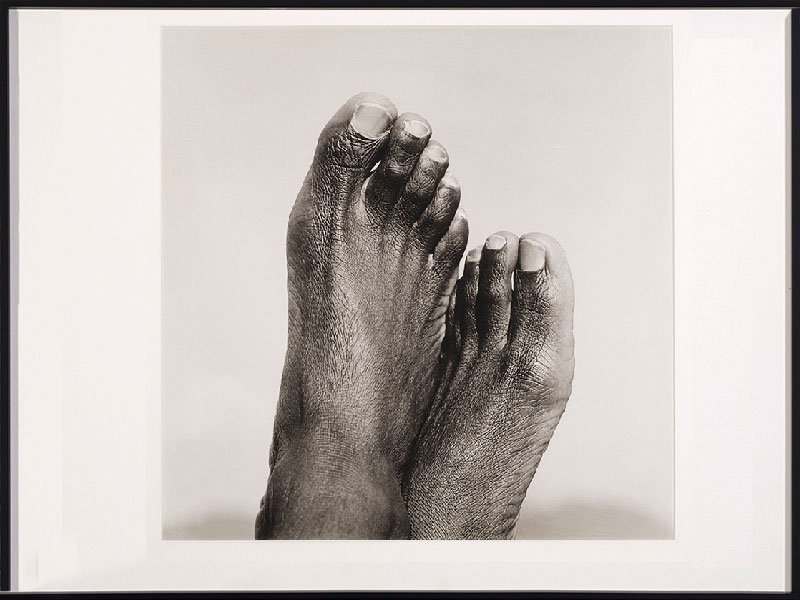

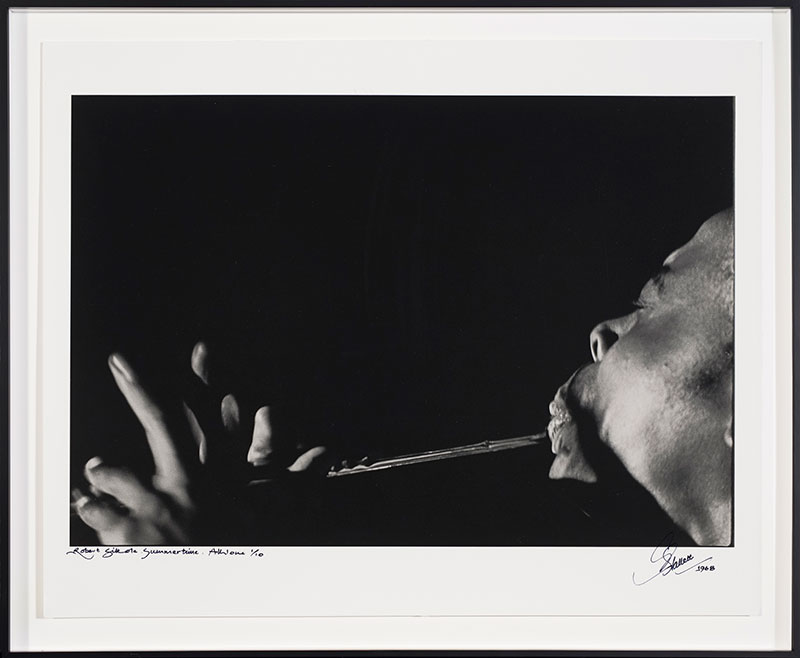

Robert Sithole playing penny whistle in Athlone. Photo George Hallett.

But easy access is essential to keeping this heritage alive.

Hallett was born and raised in District Six and later lived in Hout Bay. The self-taught photographer is renowned for the images he took of District Six and its community before it was destroyed under apartheid. Hallett went into exile in 1970, living and working in London, Amsterdam and Paris.

In the discussion, Tladi said that one of Hallett’s most important contributions was his photographic documentation of the lives of other South African artists in exile such as musicians and painters.

“Eye for humanity”

Skeef referred to Hallett as “one of a core group of radical South African photographers, who included Rashid Lombard, Jimi Matthews, who drew the world’s attention to the South African creative cultural struggle, both at home and abroad, through the accurate and far-reaching focus of his lens”.

Recalling the times they had spent together in London in the 1980s, Skeef said Hallett had an “eye for humanity” and his work documented marginalised people and spaces.

“George Hallett’s love led him directly into people’s hearts.”

“George Hallett’s love led him directly into people’s hearts. This made his camera lens both a perspicacious eye and a lance that extended his penetration into the soul of his subject. In this way, he was able to resonate with their deeper humanity.”

His photography was intrinsically a political statement, “an expression of his service to the political cause of freedom”, said Skeef.

“But this was never at the expense of his highly developed aesthetic sense as an artist devoted to elevating the human spirit.”

Hallett also inspired a younger generation of photographers such as Cedric Nunn, Matthews and Peter McKenzie.

In the discussion Tladi said the George Hallett project gave a clearer picture of the amount of work that lay, “highlighting the iceberg within our heritage”.

“That really matters in our struggle … and it’s absolutely important that he has to be introduced to the heritage canon of South Africa.”

“[But] every artist begs the same attention we are beginning to give George Hallett. We need to canvass people into our cultural icons so that when we start speaking about heritage, we can begin to understand that the pride of a nation lies with its artists,” he noted. “While we should work towards a George Hallett pictorial museum, we should have a Gerald Sekoto museum and a Gavin Jantjes museum.”

Opportunities

There are bigger opportunities in the project, said activist and artist Lorna de Smidt – taking this knowledge into schools, via the provincial Departments of Education, through funded programmes that will build training and awareness.

“And to integrate artists into our art schools and academies,” said Tladi, “so that students can learn about dedication and commitment from these people. Because, actually, the tide of the nation is with its artists.”

“Research is one of the big gaps we need to fill, not only with information but with people.”

Archiving and researching this work will also create opportunities for young scholars looking for a profession in the visual arts, Tladi said.

“Research is one of the big gaps we need to fill, not only with information but with people who will become professionals in their field.”

In closing, Skeef said that the Conversation Series provided a foundation to take this work forward.

“I look forward to a time before I shrivel and completely disappear, when I will be back in my country, our country, witnessing and participating in the manifestation of that kind of vision of education through the arts, like we were involved in during the Black Consciousness Movement. And it’s needed now more than ever.”

Layne added: “We need a broad movement to ensure that our memory as people, part of a bigger world, is intact. And that kind of archival activism or artistic activism is the power of this kind of inspiration … There’s something bigger than all of us that we’re trying to build – and that needs to involve human creativity at the centre of it.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.