Speculating on the speculum – could a redesign help to save lives?

11 March 2024 | Story Lisa Templeton. Photos Je’nine May. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time >10 min.

For over 150 years the duck-billed cervical speculum has tormented women the globe over. Invented by a man in 1870, based on an earlier prototype that started life as a gravy spoon, with prior designs dating back to ancient Greece and Rome, patients would argue it is a diagnostic tool long overdue for a redesign. On 4 March 2024 postgrads and postdocs gathered in the cafeteria at UCT’s Institute of Infectious Disease and Molecular Medicine (IDM) to do just that.

Often metal, although the plastic disposable speculum is now widely used too, women find it cold, invasive and uncomfortable. Its role is to open the vagina for visual inspection and to allow access for a pap smear screening test for cervical cancer. In this, many clinicians feel it does a great job. Patient experience and clinical viewpoints may differ.

“The redesign idea came about because I had just been through this experience, and came out thinking I would really like the speculum to be redesigned,” said Dr Fezile Khumalo, a Carnegie junior research fellow at IDM.

“I went down a complete rabbit hole looking into the history of the cervical speculum and what may have changed over time. Basically, nothing has been done for 150 years.”

“The genital inflammation test is a low-cost rapid test for vaginal inflammation, one of the biggest drivers of HIV risk in young women.”

The result was a phone call to the UCT Hasso Plattner School of Design Thinking Afrika (d-school Afrika), leaders in design-lead thinking, and a planned webinar on human papilloma virus (HPV) awareness morphed to include the design-a-thon, essentially to garner an understanding of women’s experiences of the speculum and to begin re-thinking alternatives.

Enter the d-school Afrika, the IDM and the team behind Gift – a proudly South African innovation. The genital inflammation test is a low-cost rapid test for vaginal inflammation, one of the biggest drivers of HIV risk in young women, which is currently in clinical trials. It is the result of a collaboration of almost entirely women scientists, led at UCT by Professor Jo-Ann Passmore.

“Design Thinking is a process for solving problems by prioritising the user’s needs above all else,” facilitator Annie van Niekerk of d-school Afrika, wrote on the board. She had been breaking ice with fun exercises given the sensitivity of the topic. By the end of the morning everyone in the room was prioritising the ‘user’ as the patient being examined.

A barrier to a potentially life-saving check up

The issue goes so much further than physical discomfort. It is emotionally deeply uncomfortable too, as someone in the audience said: “My gynae was chatting as if we were having tea, and my vagina was wide open.”

Not all clinicians are sensitive, and not all women are aware of the health risk of HPV or cervical cancer.

The net result is women stay away from a test that could save their life, and it becomes a huge adherence issue from a public health perspective.

“We have a problem the rest of the world doesn’t have,” said Boipelo Selebano, who is doing a master’s in medical biochemistry at the Department of Integrative Biomedical Sciences (IBMS).

“While, globally, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women, 94% of deaths occur in low- to middle-income countries, with some of the highest rates of cervical cancer and mortality in sub-Saharan Africa, and notably South Africa.”

Some 95% of cervical cancers are caused by HPV infection, something almost all sexually active people, male and female, will get at some point. While ordinarily there are no symptoms and the immune system clears HPV, persistent infection of the cervix with high-risk HPV can develop into cancer if left untreated. Women living with HIV are six times more likely to develop cervical cancer, and 20% of children who lose their mother to cancer, do so to cervical cancer (World Health Organisation).

And it is almost entirely avoidable thanks to a vaccine. In addition, it can be cured with early detection and prompt treatment.

Public awareness and access to screening

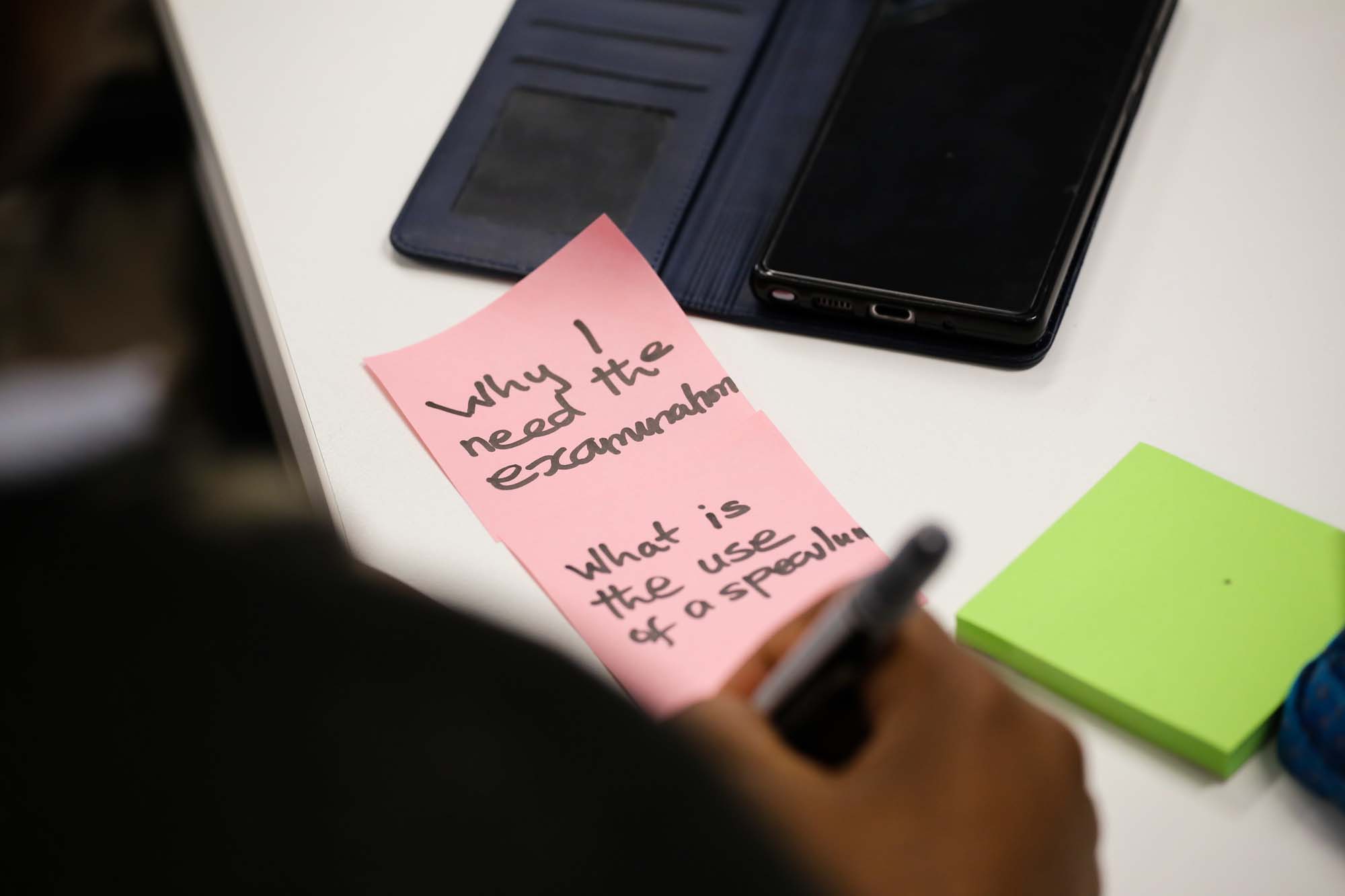

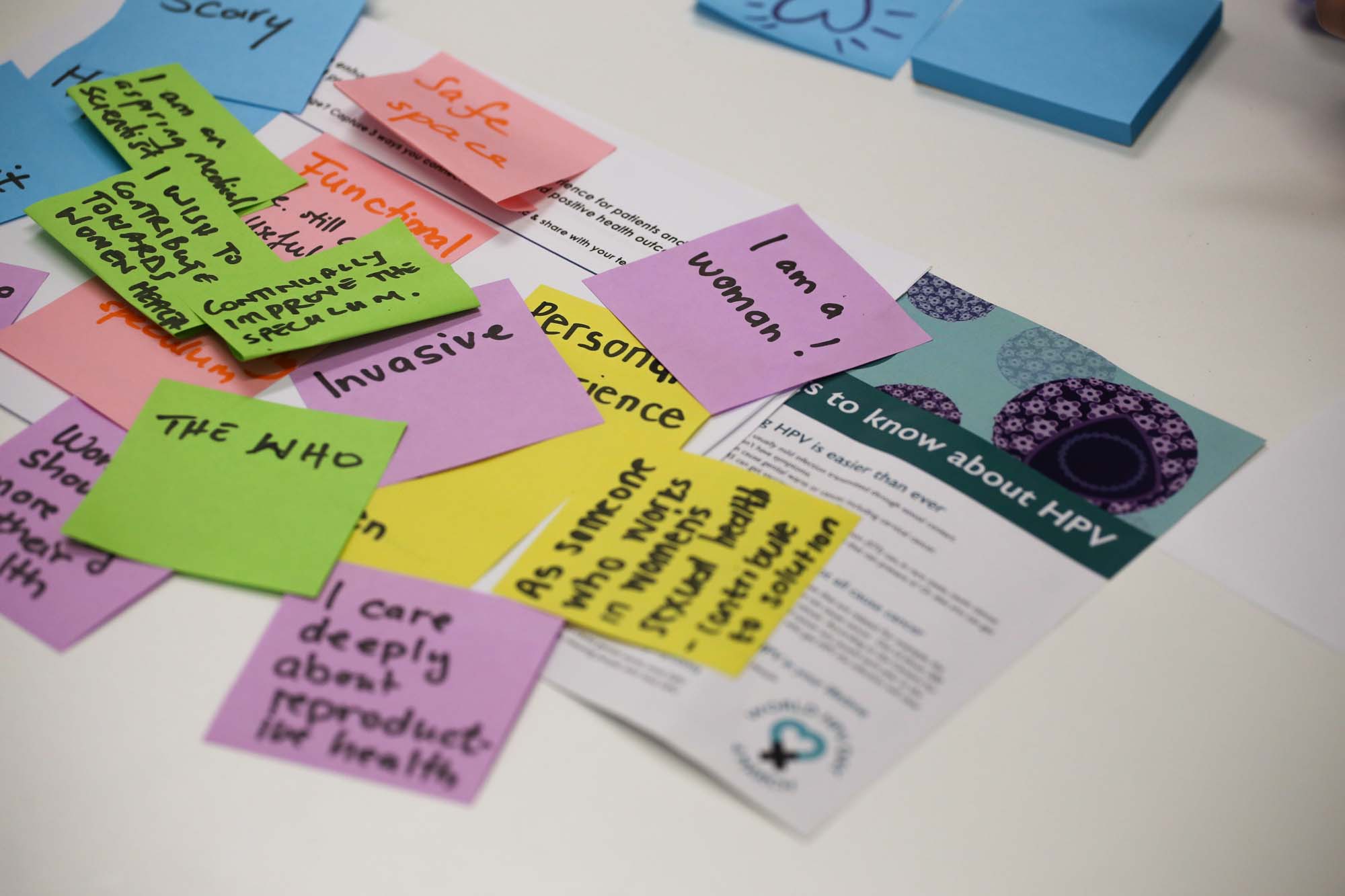

Divided into teams by Van Niekerk, within the safe space created by the d-school Afrika design-thinking process, the participants set about discussing first the problem, and later the solution. A volunteer from each table was interviewed by a team other than their own to find out more about their pap smear experiences.

“I had no idea that this shared experience was so universal,” said Michael Goldshagg, a master’s student in cell biology, who was there because while his research looks at cervical cancer in deep and technical detail, he does not know much about what goes into the diagnosis and treatment.

“It seems that fear prevents early diagnosis because women avoid screening, preferring to think; ‘it’s probably fine’ and avoiding a check-up.”

“It seems that fear prevents early diagnosis because women avoid screening, preferring to think; ‘it’s probably fine’ and avoiding a check-up. No one talks about the issue, and yet when it is caught earlier, there is a much better chance of beating it.”

Yulisha Naidoo, the research visibility officer at the IDM, and a master’s in public health candidate, felt the same way. “When it comes to women’s health, we are conservative. We need to be vocal about female problems. Adherence to preventative examinations, like a cervical screenings, is difficult to measure, and many women opt out if there is a choice.

“We need change to make women want to be more compliant in wanting an examination.”

So, what is the solution? The teams verbally came up with solutions to speculum alternatives before hitting the arts and crafts table to create a model of an alternative to present to the workshop. Everyone reinvented the wheel with great enthusiasm.

Two teams came up with prototypes that worked telescopically, as a tampon applicator might, while a third looked at a dye and external screening option. One team’s tampon approach empowered women to do an initial self-screening, with the potential help of an app, a small brush for cell samples and camera for picking up disparities.

All solutions were woman-friendly

“Today ticked all my boxes,” said Felicity Hartley, a fine artist who has just completed a master’s in philosophy, medical virology, and who has a self-confessed passion for creative methodologies in promoting or examining sexual reproductive health.

“I loved that some ideas overlapped. It means we are on the right track and unanimous that something must be done with regards to alternatives to the speculum, lack of awareness, and compassion around pap smears, and the need for self-empowerment that care providers need to encourage when doing something like this.”

Takunda Ngwenya, a doctoral student in medical virology with an interest in women’s health, found the morning, “very valuable”.

“It gave us a real insight into rethinking everything around cervical cancer screening. It was helpful to build a prototype that could, hopefully, improve the diagnosis of cervical cancer in women.”

Going forward

Dr Khumalo noted: “This morning made me recognise there is a long road ahead. We are not going to get to a reimagined speculum from one session.

“There is so much to consider. We have scratched the surface and recognised pain points. Today was about understanding women’s experiences. As we continue on this reimagining journey, we will include doctors, clinicians, nurses and midwives to get their input.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.