Blind, visually impaired learners use LEGO to learn through play

27 September 2024 | Story Niémah Davids. Photos Lerato Maduna. Videography & video edit Ruairi Abrahams. Video production coordination and research Nomfundo Xolo. Read time 7 min.From a distance outside the Grade 3 classroom, it sounded like just another English language lesson – with a teacher at the blackboard and a group of boys and girls taking instructions at their desks with a pencil in hand. But it was very different.

Learners at the Athlone School for the Blind don’t use pencils and paper, they use braille – a tactile reading and writing system designed especially for people who are blind or visually impaired. It allows them to read, spell and communicate without the use of conventional media.

So, for this group of learners, the pen is not necessarily considered mightier than the sword because they communicate differently – but with the same excited energy as their sighted counterparts at mainstream schools.

A language lesson with a difference

“This morning, we will focus on language. What do we call words that sound the same but have different meanings and spelling?” Sharlene de Oor, a Grade 3 teacher at the school, asked. Almost immediately a little voice pipped up excitedly from the back: “I know! That is a homophone, teacher!”

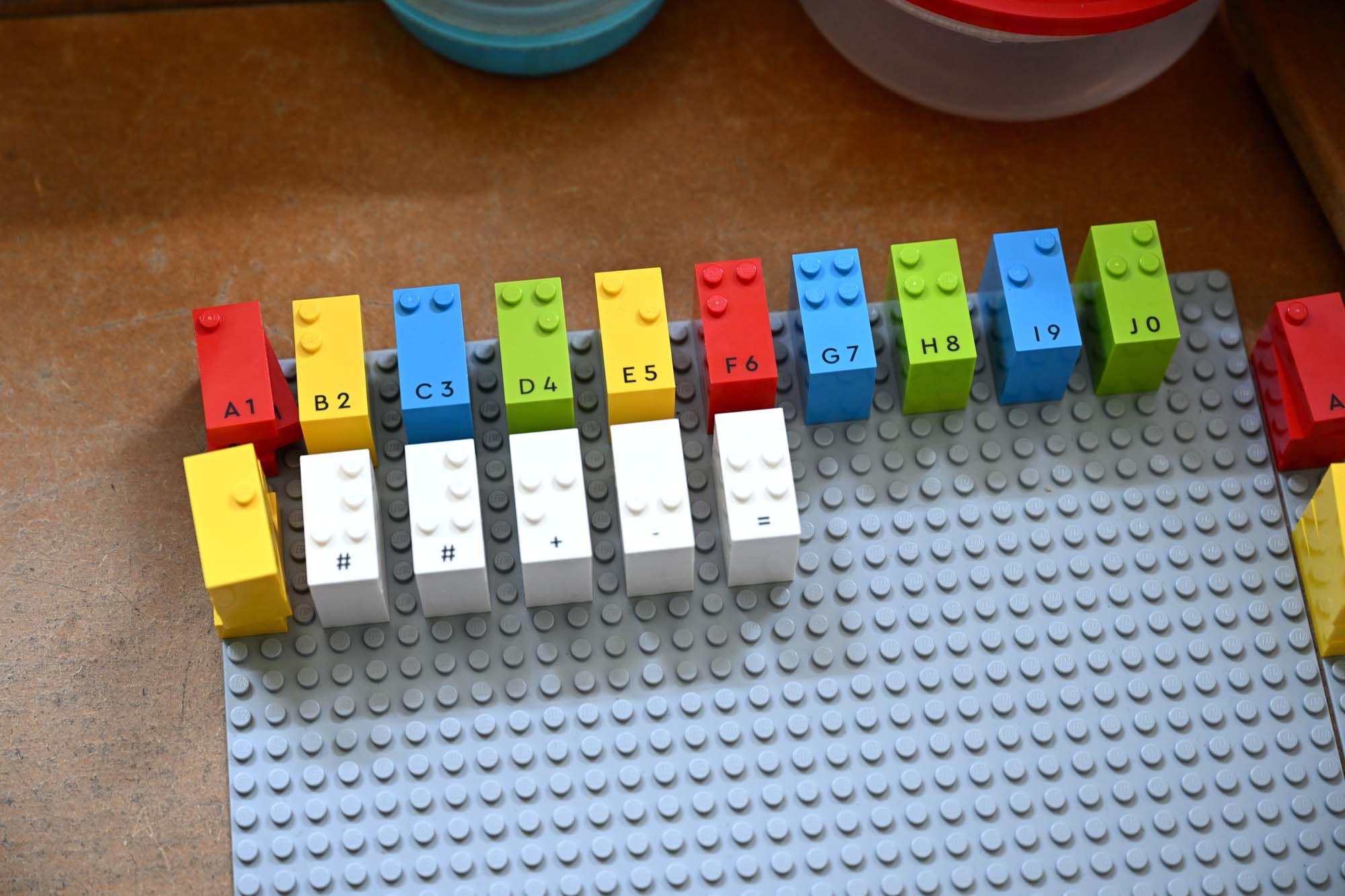

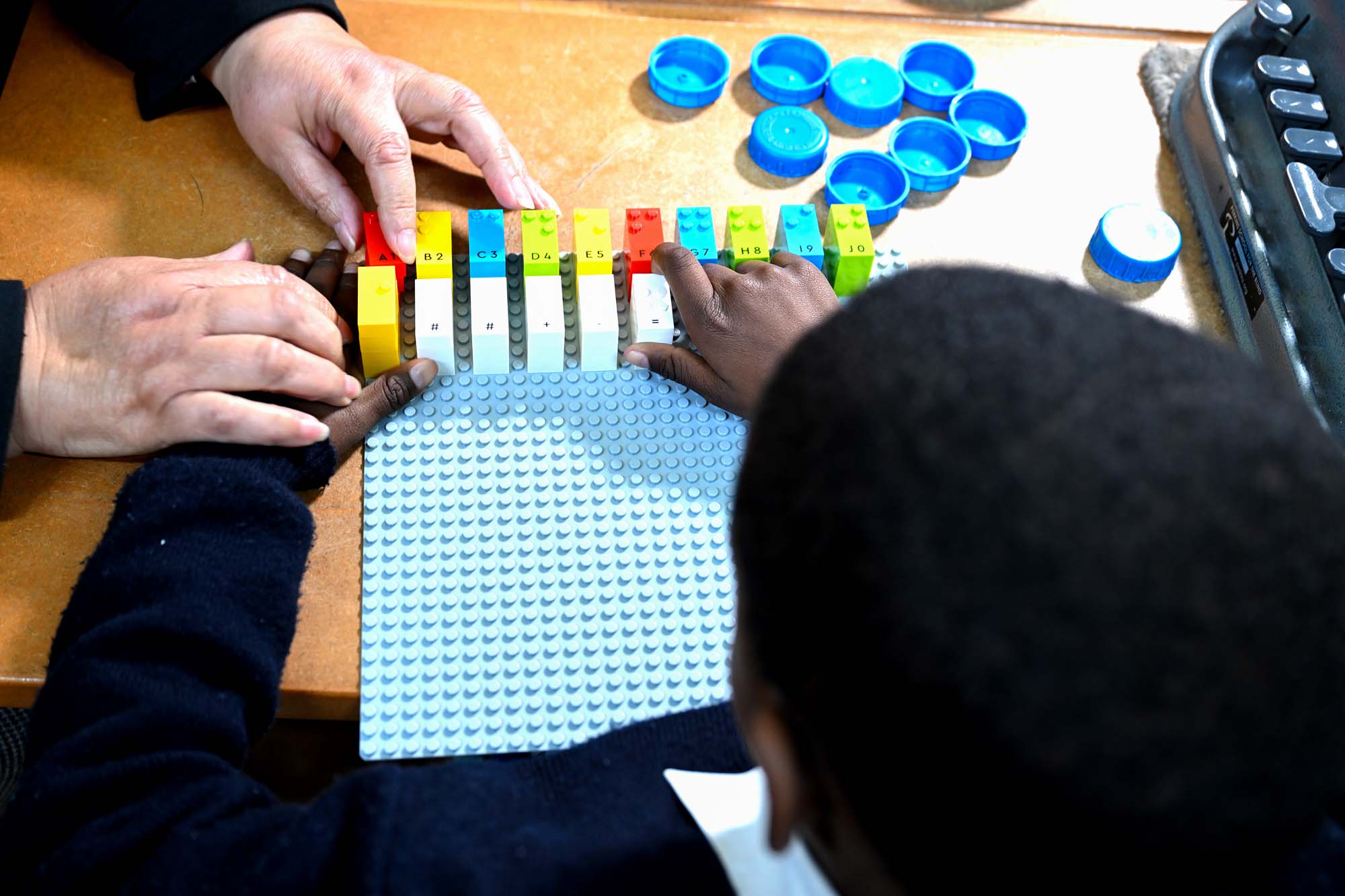

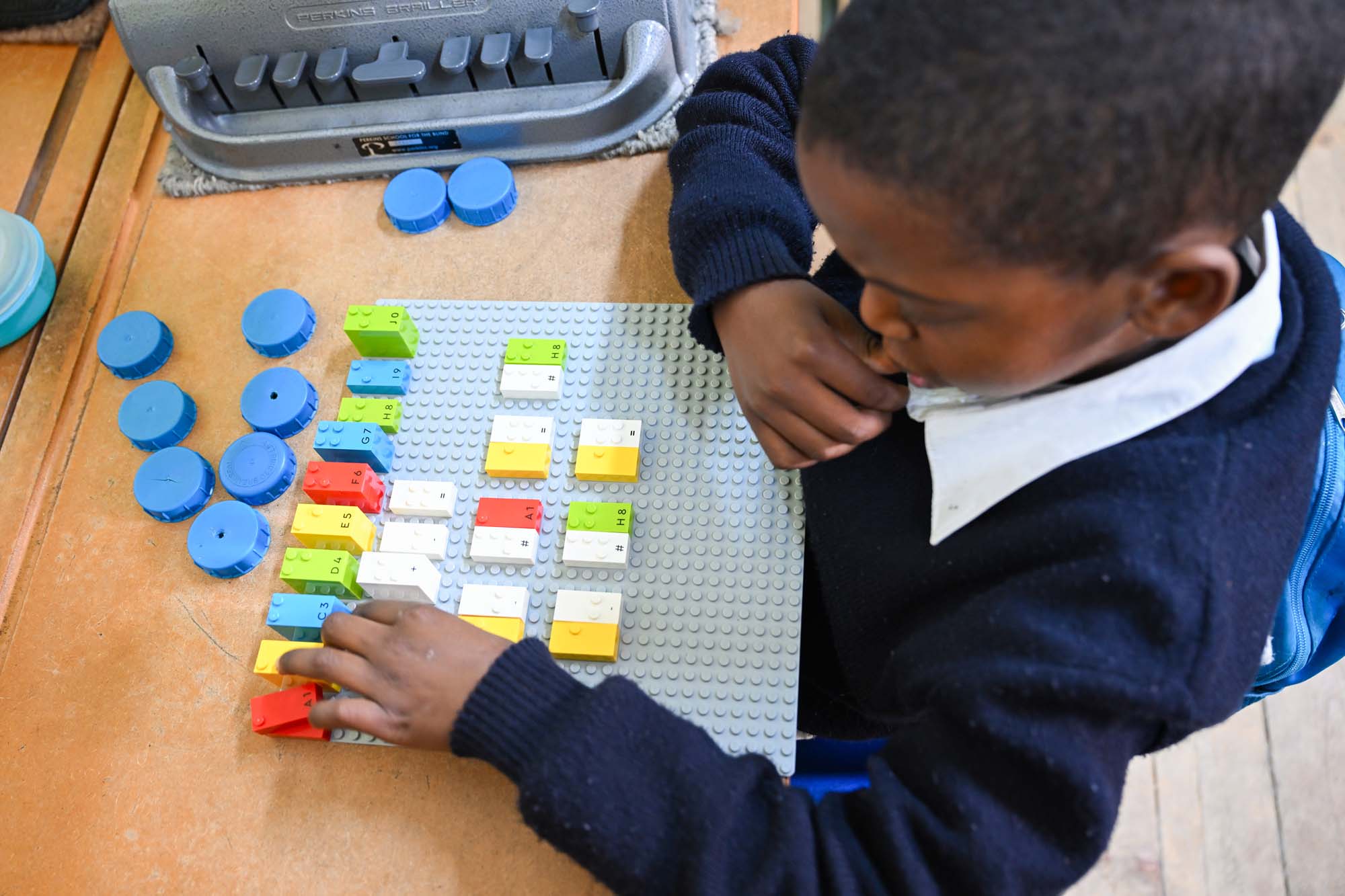

De Oor then instructed her class to provide at least one homophone and asked them to spell the word. Using their LEGO Braille Bricks, they did exactly that. Teachers and learners at the Athlone School for the Blind are participating in the LEGO Braille Bricks project – a playful methodology that aims to teach braille to children who are blind and visually impaired using LEGO. Each colourful brick is moulded with studs that correspond to numbers and letters in the braille alphabet and also include a corresponding printed symbol or letter.

The innovative project is spearheaded by the LEGO Foundation, in partnership with the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Including Disability Education in Africa (IDEA), BlindSA and four schools for the blind in the Western Cape and Gauteng. Currently in an extended pilot phase, the initiative aims to level the playing field between sighted and blind children because it allows them to play and learn simultaneously.

Reading with LEGO

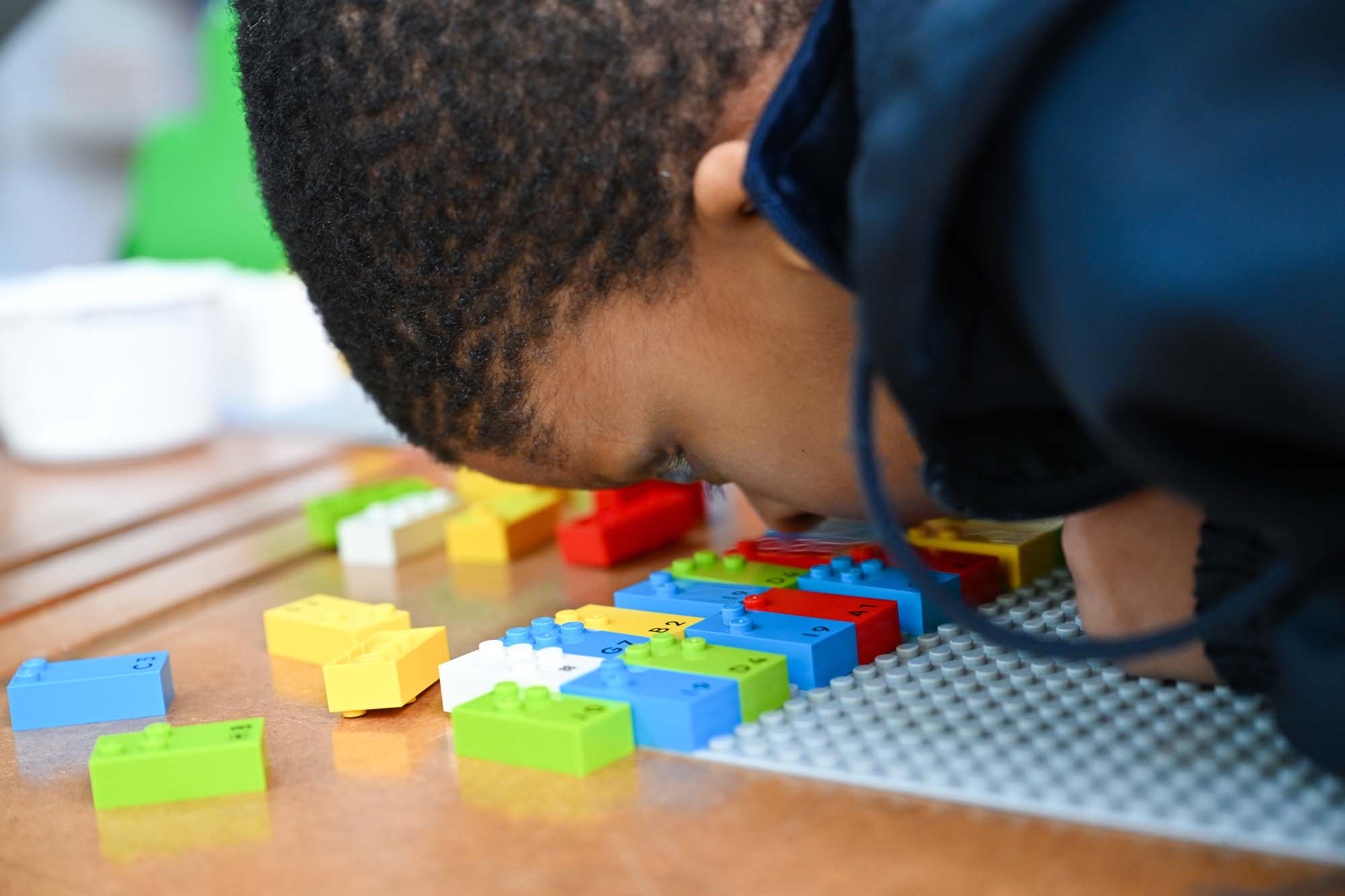

As learners in De Oor’s class proceeded with their language lesson, chose a homophone of their choice and eagerly spelt their words using the LEGO Braille Bricks, Lukho Cebiso said she enjoys interacting with the LEGO.

“I can [spell and] pack [many] words [using the LEGO Braille Bricks], words like watch, pot, bird and [the names of different] insects.”

“I can [spell and] pack [many] words [using the LEGO Braille Bricks], words like watch, pot, bird and [the names of different] insects. I enjoy that,” she said.

And more than spelling, the bricks have also unlocked Cebiso’s creative mind. She said it has allowed her to build a house and to design and configure it the way she wanted. She said she recently built a single-storey house, with one bedroom, a bathroom and a kitchen that includes storage cabinets, a fridge and a stove and an oven for cooking and baking.

As a class, Cebiso said, the learners also use every free moment to spell and interact with the LEGO, with De Oor’s permission, of course.

“Sometimes when we’re not busy, we ask teacher [if] we can use the bricks to pack in words and sentences. And it helps me with sounds, numbers and punctuation,” Cebiso said.

A teacher’s take

When the Athlone School was approached to join the project, Deidre Paulse, a Grade 1 teacher, said staff were as excited as the learners about the prospects of teaching and learning using LEGO and were eagerly anticipating the positive outcome for their learners. And when they got going, she said they discovered that using the bricks is not one-dimensional. In fact, it benefits the learner in a myriad of ways. As a start and in line with its intended purpose, she said, the bricks help learners to read and spell and also assist with developing their fine motor skills, as well as positioning and spatial relationship skills.

“Fine motor skills and spatial relationship skills are of the utmost importance for children who learn braille. If they struggle with that then there’s a challenge to teach braille. So, it was nice that the LEGO Braille Bricks helped with that too” she said.

What’s more, Paulse said teachers can also use the interactive games that accompany the programme, and easily incorporate those into the curriculum to foster a unique culture of learning through play.

“In the beginning we just thought braille bricks, we didn’t see the bigger picture. But having worked through it in the last few months, we’ve seen a lot more and we’ve also seen what else we can do with it and how it benefits our learners,” she said. “The children are excited and enjoy working with the bricks.”

Using LEGO as an enabler to teach braille

IDEA’s Dr Richard Vergunst said the team is thrilled by what they’ve observed over the past few months. The project is now in its second phase and is being put to the test among teachers and learners at special-needs schools. Since the trial got under way, he said priority one has been to train teachers to use the bricks effectively, to monitor and evaluate the roll out, as well as the pros and cons through ongoing research (observations, focus group discussions and surveys). The primary goal is to understand whether the project is contextually relevant in South Africa and how it can support the development of an inclusive education system in the country.

“Our role is to negotiate with the LEGO Foundation on how we will move beyond this pilot phase, if we get to roll out at scale nationally.”

Based on the data that teachers provide, Dr Vergunst said it will give researchers an indication on the success of the project and whether it will be feasible to continue its roll out on a broader, national level. The latter, he said, is crucial. If successful, key questions like what the roll-out and implementation process will look like and who will be involved, need to be answered. He said researchers have already identified that teachers need ongoing support to facilitate the project long-term. This, he added, could mean continuous training and support group sessions to monitor and guide them.

“But we can’t leave teachers by themselves to run with the project. They need support and guidance. Our role now is to negotiate with the LEGO Foundation how we will move beyond this pilot phase, if we get to roll out at scale nationally,” he said. “What we have seen is that there is a keen interest, energy and enthusiasm for the project. People think it’s worthwhile and relevant and want to continue using it”.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.