A champion on the track and beyond

30 September 2024 | Story Nicole Forrest. Photo Andries Kruger. Read time 8 min.

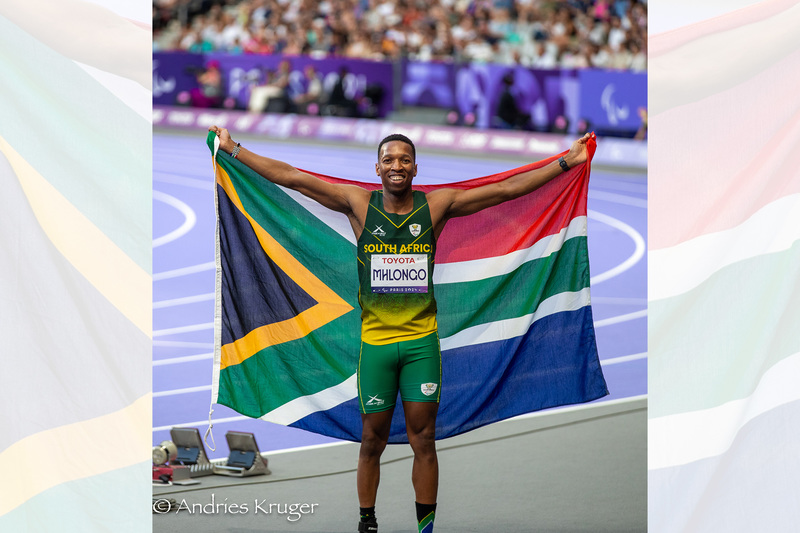

University of Cape Town (UCT) chemical engineering PhD candidate and Paralympian Mpumelelo Mhlongo brought home a gold and bronze medal along with two world and Paralympic records from the Paralympic Games in Paris. He spoke to UCT News about life as a Paralympian – both on and off the track.

Although Mhlongo has competed in two previous Paralympic Games – the first in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 2016; and the second in Tokyo, Japan, in 2020 – this event was particularly memorable for him. And not just because of the medals and records he secured.

“It was the first time at a Paralympic Games that our newly formed class, the T44 class for athletes with lower limb deficiencies, had its own race,” he said.

“It was great to see a display from people in this class who would never have made Tokyo or Rio, not because they didn’t have the ability, talent or dedication, but because they were put into a class where their capabilities weren’t matched with other athletes.”

Considering the effort that it took to have this class recognised by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), it’s no surprise that this was one of Mhlongo’s highlights.

“There are a lot of people in this class who can now represent their countries.”

“The journey was difficult. It was basically a two-year journey of legal debates and interpretations until the IPC eventually conceded and said that they agreed with what we were putting forward,” he explained.

“My coach, myself, one of the Italian athletes, the Italian sporting federation and the German federation had to show that the grouping was unfair. We had to prove that the current legal wording of the T44 class applied to athletes with single lower leg deficiencies but, because of how it’s manifested over the years, became known as the amputee class.

“There are a lot of people in this class who can now represent their countries – and it’s exciting. Just being with those athletes and being able to say that we were a part of Paralympic history, knowing that without our efforts we probably wouldn’t have been there, was a highlight.”

From stigma to success

Despite the waves that he’s made in his disciplines, Mhlongo’s journey to the Paralympics wasn’t one borne out of an early ambition to become an athlete. Rather, it was shaped by a desire to overcome the stigma surrounding disabilities that’s so often rampant in small-town South Africa.

“When you’re born with a deformity or a disability, it’s almost always associated with some sort of witchcraft or black magic. So, really, I just wanted to be the fastest kid in the block so that I wasn’t known as the kid with a disability or the kid with the chicken foot that is potentially contagious. It was my way of fitting into a community that couldn’t really grasp what my deformity meant,” he said.

“When you’re born with a deformity or a disability, it’s almost always associated with some sort of witchcraft or black magic.”

What began as a personal challenge to run faster than his peers soon turned into a competitive opportunity. His athletic potential became clear when he began representing his district and later his province. However, it wasn’t until university that his journey to the Paralympics truly began.

Running with fellow disabled athlete Vukile Skoti, an arm amputee, at a provincial athletics championship, changed the course of Mhlongo’s life when Skoti noticed and pointed out his potential as a Paralympian.

“After our race, he said, ‘You could be a Paralympian; you could wear green and gold.’ Then he taught me what all of the classifications mean and showed me the systems and the ropes. That’s when we represented South Africa in 2015 and I’ve never really looked back,” he recalled.

The accidental engineer

Mhlongo’s academic career mirrors his athletic one; not only because of the Paralympian’s outstanding achievements, but also how he came to find himself in his field of study.

“Chemical engineering was chosen for me, if I’m honest. I was in the choir at high school and we went to the World Choir Games. So, when everyone else was doing their university applications, I was singing in America,” he said.

“I’d left my mom with the mandate of applying for either architecture or fine arts – or both – but she wasn’t convinced that art was the right career path for me. So, she conspired with my maths teacher and they decided that I’d do either chemical engineering or actuarial science.

“A large portion of the skills you develop relate to process optimisation; figuring out the most efficient and effective solution, just like on the sports field.”

“When I came back, those were the two options I had. I didn’t enjoy stats, so I chose chemical engineering, not really knowing what I was getting into. But it all worked out and I’m grateful for them picking such a constructive path for a young man.”

After completing his bachelor’s, Mhlongo began work on his master’s and was soon upgraded to a PhD. His research focuses on converting plastic waste to energy, which presents major opportunities in the green economy.

While they may appear to be worlds apart, there is considerable overlap in these two areas of his life. “A large portion of the skills you develop relate to process optimisation; figuring out the most efficient and effective solution, just like on the sports field,” he said.

Mastering the art of imbalance

Looking at his impressive string of achievements in almost every area of his life (in addition to being a top athlete and pursuing a PhD, Mhlongo speaks six languages and has a talent for art), it’s natural to wonder how he manages to do it all.

“Unfortunately, there’s no balance,” he laughed. “One of my mentors sat me down a long time ago and told me that you can have everything in life – if you live long enough – you just can’t have it all at the same time,” he recalled.

“You have to forget about doing everything all at once and know that there are things that will take priority at certain points in your life and other things that will be important at other times. What’s important is that you communicate that well so that everyone in your life knows where you are and what’s important.

“That’s how you can go forward and achieve those singular milestones, with daily discipline. Then, in 20 years’ time, when you look back, you could be living out a reality you would not have been able to dream of.”

Mhlongo’s Paralympic results

Men’s 100m (T44): Gold, World Record, Paralympic Record

Men’s 200m (T64): Bronze, World Record (T44), Paralympic Record (T44)

Men’s Long Jump (T44): World Record, Paralympic Record

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.