Thinking outside the narrative box

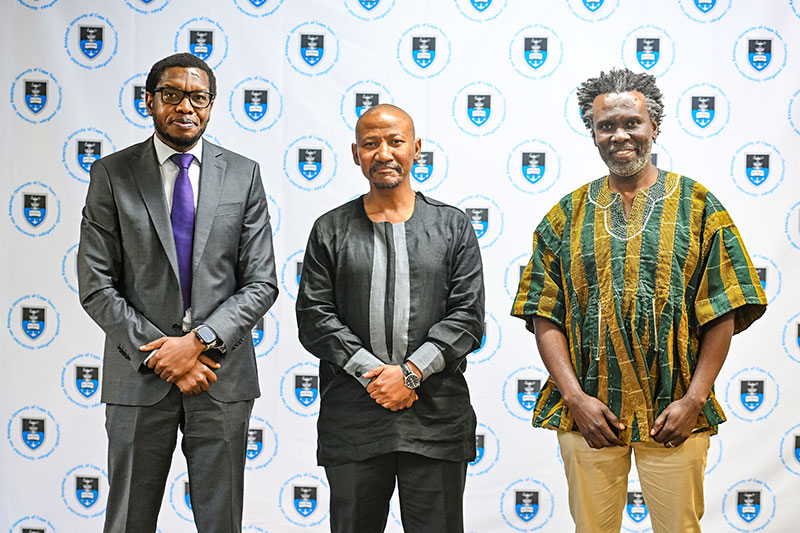

03 October 2024 | Story Kamva Somdyala. Photos Lerato Maduna. Video Production Team Ruairi Abrahams, Boikhutso Ntsoko and Nomfundo Xolo. Read time 10 min.The International Court of Justice (ICJ) swore in then Professor Dire Tladi as the first-ever South African judge on its bench in February this year. Over 200 days later, Judge Tladi delivered the 58th TB Davie Memorial Lecture at the University of Cape Town (UCT) on 1 October.

The TB Davie Memorial Lecture was established by students at UCT to commemorate the work of Professor Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice-chancellor of the university from 1948 to 1955, and a defender of the principles of academic freedom.

Hosted in conjunction with acting chairperson of the Academic Freedom Committee (AFC), Professor Rudzani Muloiwa, Tladi accepted the invitation and delivered a lecture of caveats, examples and illumination.

The caveats were that he was not going to speak about the ICJ’s current and potential future cases for obvious reasons; he revisited his thoughts around South Africa’s Omar al-Bashir saga in one example and revealed that the topic of his talk, “The Narrative as the Enemy of Freedom of Thought”, is also going through its own refinement.

Principal judicial organ

Tladi was elected by the United Nations (UN) General Assembly and Security Council on 9 November 2023. The ICJ is the principal judicial organ of the UN and one of the six principal bodies of the intergovernmental organisation.

The court’s role is to settle, per international law, legal disputes submitted to it by states and to give advisory opinions on legal questions referred to it by authorised UN organs and specialised agencies. He will serve a nine-year term.

He began by saying that his title will be a little bit broader. “It will be broadly about the tyranny of narrative, so not restricted to freedom of thought but to freedom in general, with some bias towards freedom of thought. I would say the theme of the talk is the ‘Potential Tyranny of the Narrative’. As an international lawyer, the topic is presented through the prism, not so much of international law, but rather of events relevant to international law.”

“Narratives provide a possibility for taking events that are known to us and using them to represent the state of the world.”

“I want to begin by explaining that the topic, as originally conceived, was an intuitive topic, based on my personal experience as a victim of the narrative. So, for me, the word ‘narrative’ was not a scientific, academic or intellectual term. It was a word that I had conjured up when thinking about events in my experience initially as a diplomat and then later as a lawyer,” Tladi said.

He first used the word ‘narrative’ in 2011. He was at a Security Council Consultation Room as a legal adviser of the South African permanent mission in New York, discussing the text of a resolution that was eventually Resolution 1970 – the resolution referring the situation in Libya to the International Criminal Court (ICC).

“I recall saying to the ambassador at the time that the ‘narrative’ created pressure on us to vote in a particular way, although there may have been good legal reasons not to support [the resolution]. A narrative, simply put, is a story. A dictionary will tell you that it is an account of connected events, which is used to tell a story. In this context, narratives provide a possibility for taking events that are known to us and using them to represent the state of the world, to create (or to re-create) the world, or a view of the world ... perhaps to re-imagine it.”

Tladi added: “As human beings, we are entitled, [and] should be entitled, to freedom of thought regardless of how unpopular those views [are]. This is particularly true when you have been elected to a position that requires you to exercise independent thought and judgment. The vitriol is a particularly disconcerting example of the tyranny of narrative.”

It was, at this point, that he turned to share how he too was the subject of the tyranny of the narrative on several occasions, but no more prevalent than the Al Bashir case which swept through the country in 2015.

Lawful arrest untenable

“I have never questioned the narrative – it may or may not be true [that he was guilty of one of the worst cases of genocide against the Darfurians]. The fact that a court of law, like the ICC, felt it had sufficient evidence to indict and issue an arrest warrant made it at least plausible. But whether the narrative was true or not is, in this case, immaterial, so let’s assume that it was true … while I accepted the narrative, and accepted that the ICC was justified in seeking to try him in The Hague [ICC location], I also argued, on the basis of international law, a subject on which I have some expertise, that South Africa could not lawfully arrest him.”

Hate messages followed his opinion pieces and conversations on this. And for him, there were two problems with the atmosphere created by the narrative.

“The tyranny of the narrative is made possible by the creation of angels and demons, heroes and villains.”

“First, because of who he was, he was no longer entitled to the protection that the law may offer to others. The law on immunity was not a figment of my imagination, it was real, and incredible gymnastics had to be performed to create the illusion that it did not exist. Second, the power of the narrative meant that anyone who presented, even reasonable arguments, that might be interpreted as undermining the narrative was ostracised. So, freedom of thought, freedom of expression and freedom of judgment are curtailed,” Tladi added.

As he drew to a close, he put his narrative conversation to the test: “The tyranny of the narrative is made possible by the creation of angels and demons, heroes and villains. Heroes and angels can do no wrong, and villains and demons can do no right. The creation of narratives becomes a powerful tool for shutting down conversation and violating the right of persons that either question the narrative or, even if they accept it, seek to draw attention to nuances.”

“As human beings we are programmed to make sense of the savagery and violence, and we do this by creating narratives. Narratives are normal process by which we can make sense of the events in our world. Narratives allow us to make decisions about what course of action to take to correct what’s wrong with the world,” he said.

“When narrative comes face to face with, and undermines, freedom of thought and freedom of expression; when narrative becomes the enemy of freedom, it is when that happens, that the tyranny of the narrative reveals itself.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

TB Davie Memorial Lectures

In the classic expression of freedom of speech and assembly, UCT's policy is that our members will enjoy freedom to explore ideas, to express these and to assemble peacefully.

The annual TB Davie Memorial Lecture on academic freedom was established by UCT students to commemorate the work of Thomas Benjamin Davie, vice-chancellor of the university from 1948 to 1955 and a defender of the principles of academic freedom.

Organised by the Academic Freedom Committee, the lecture is delivered by distinguished speakers who are invited to speak on a theme related to academic and human freedom.