Rewriting a piece of history

04 November 2019 | Story Niémah Davids. Photo Brenton Geach. Read time 6 min.More than a century after they died, and almost 90 years after the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Faculty of Health Sciences (FHS) unethically obtained the skeletal remains of nine people from the Sutherland area of the Northern Cape, a significant part of their history has been revealed.

Present-day scientific analysis indicates that most of the group, comprising five men, two women and two children, had all lived in a dry, mainly winter rainfall environment just like that of Sutherland.

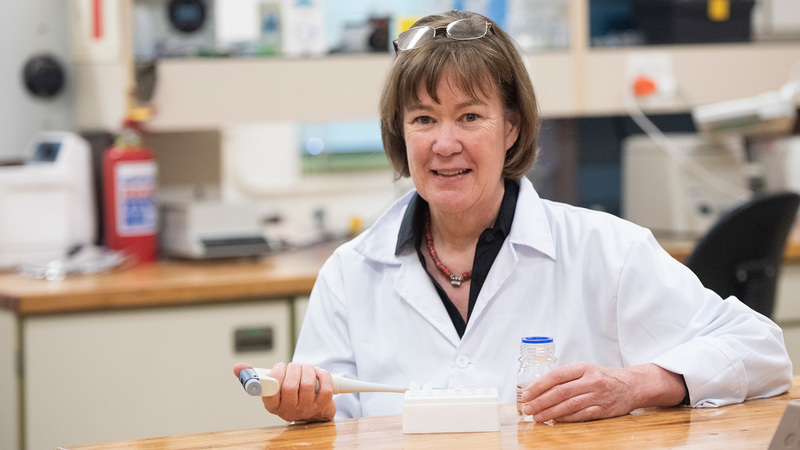

This is according to Professor Judith Sealy, from UCT’s Department of Archaeology, who was tasked with analysing the bones and teeth of the Sutherland individuals, to help determine their origins, as reflected in the chemistry of the foods they ate.

In 2017, following an archival audit, the FHS discovered that its skeletal collection included several that were obtained unethically between 1925 and 1931. The limited documentation available indicated that some members of the group had been captured and forced to work on a farm near Sutherland, and died there in the 19th century.

After their deaths, it is believed that the skeletons were removed from their graves by the owner of the Kruisrivier farm and sent to the university unethically for teaching and research purposes.

After the discovery, UCT began an investigation into how it could return the skeletons to their rightful home, to rest near their descendants.

Fact finding

As part of a restorative process to learn more about them, and ultimately to return their remains to an appropriate, final resting place, Sealy joined other leading academics in various disciplines from UCT, as well as academics from the projectʼs partner universities – Max-Planck-Gesellschaft (MPG)’s Max Planck Institute (MPI) for the Science of Human History in Germany, and the Liverpool John Moores University in the United Kingdom – in a multidisciplinary project to help piece together answers to important questions about the individuals.

Using stable isotope analysis, or analysis of the nonradio isotopes that occur naturally in all living isotopes, Sealy was able to draw conclusions about the nine individuals’ diets and the environment in which they lived.

“That has helped us to resolve some of the arguments about the origins of these individuals and that’s been an important finding.”

“The composition of the Sutherland individuals clearly reflects [that they] came from and lived in an arid environment like Sutherland, not like other, wetter parts of South Africa.

“That has helped us to resolve some of the recent arguments about the origins of these individuals and that’s been an important finding,” Sealy said.

Teeth and bones

To determine the diet the nine individuals consumed as children, Sealy analysed samples of their teeth, and to get a sense of what they ate as adults, she studied their bones.

“The diets we eat as children are reflected in our teeth, because our teeth grow when we are children, whereas the diets we eat in adulthood are reflected in our bones because our bones grow throughout our lives,” she said.

The analysis yielded some interesting facts, she added, especially for one of the individuals – Klaas Stuurman. The archival records in the FHS skeletal collection indicate that Stuurman was captured and taken to Kruisrivier as a child. He is said to have been brought from an area between Carnarvon and Sutherland, to the north east of Sutherland.

“That’s a dryer area, an area with a slightly different climate. Indeed, we can see differences between his teeth and bones that corroborate that life history. This is useful information, since some information in the archival records about other individuals have proven to be incorrect,” Sealy pointed out.

“The value of these kinds of analytical studies is that they, together with information contributed by other [academics] in other areas of this study, give us a fuller picture of these people’s [lives].”

Eating habits

While she stressed that researchers could determine the diets of these individuals only in fairly broad categories, results revealed several commonalities when it came to the food they ate.

“Klaas and Cornelius may have eaten slightly different diets as children and therefore probably moved around in their lifetime.”

From the information available, Sealy said, it was clear the nine people consumed a diet that contained some refined carbohydrates, as well as sugar, which was evident from their teeth.

“This diet led to a high frequency of dental caries and we see that in several people.”

However, Sealy said, according to her research, Stuurman and another individual, Cornelius Abraham, seem to have had a different diet during their childhood.

“Klaas and Cornelius may have eaten slightly different diets as children and therefore probably moved around in their lifetime,” she suggested.

For Sealy, being part of the team responsible for piecing together the lives of the Sutherland nine has been a meaningful experience, and in a sense “groundbreaking” too, especially since the university was able to track down their descendants and make contact with them to begin the restorative process.

Visiting Sutherland was what really stood out for her though. She joined other academics on a trip to the area to present their research findings on the remains to the families.

“The families have been extraordinarily generous and accepting of the university, considering the difficult history that lies behind all of this. I hope that telling them about some of the information we collected will help them come to terms with what happened here,” she said.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

UCT Sutherland Reburial

After an archiving audit of the UCT Human Skeletal Collection in 2017, the university discovered that it had 11 skeletons in its collection that were unethically obtained by the institution in the 1920s. The university has acknowledged this past injustice, which forms part of its history. Nine of these individuals were brought to the university in the 1920s from Sutherland in the Northern Cape. UCT is working with the community of Sutherland to return the skeletal remains of these nine individuals to their descendants. An interdisciplinary team of academics from UCT and two international partner institutions have conducted unprecedented scientific studies. This process has enabled the university to provide redress and social justice through science.

On 26 November 2023, remains of the nine individuals were reburied in Sutherland. Read the latest news.