Ancient African science is the beginning of wisdom

28 October 2024 | Story Nicole Forrest. Photo Roger Sedres. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 6 min.

For the final session in its seminar series, Environmental Humanities South (EHS) invited activist, academic, and former vice-chancellor (VC) of the University of Cape Town (UCT) Dr Mamphela Ramphele to speak about how ancient wisdom in Africa can help lay a pathway to a better future.

A part of the Faculty of Humanities, the EHS is an interdisciplinary research cluster and postgraduate programme that aims to broaden the intellectual models, research methods and resources provided to environmental decision-makers through deep research and engaged dialogue.

As one of the founders of the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) and a global cultural leader, Dr Ramphele was a perfect fit for the final seminar in the EHS series. She spoke about how, by taking ownership of our identity as Africans and nurturing ancient traditional practices, we can reimagine the future – of both the continent and the world.

A revisionist history

In framing the discussion, Dr Ramphele noted that, while they constitute only 6% of the world’s population, indigenous people care 80% of sensitive ecosystems – a notable feat. However, she pointed out, there is a persistent failure by those in the West to acknowledge that these traditions are science and that they can be used to vastly improve the lives of millions.

“The reticence of academic and intellectuals, including African scholars themselves, to embrace ancient science that emerged from the first human civilisation in Africa, the cradle of humanity, remains. The ease with which educated people across the globe, including Africans, refer to modern sciences as ‘Western’ is historic and disappointing,” she said.

Even when Africa’s impact on Western culture and civilisation is undeniable, the former VC pointed out, there is, at best, a refusal to acknowledge this and, at worst, a rewriting of history to position the West as the originator of this knowledge.

“It is this kind of distancing of Egyptian history from its authentic African roots that has a strategic input for global power politics.”

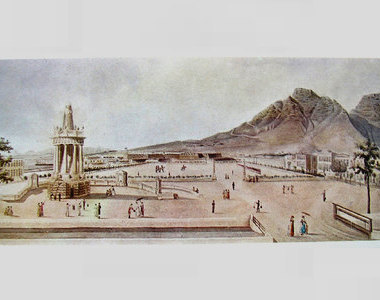

“Ancient Egypt, which was the pinnacle of a civilisation whose artefacts have been found in Nubia, left the legacy of the pyramids. These structures, their configuration and the mummification rituals that took place in them suggest a broad range of scientific knowledge – from mathematics and cosmology to biology and chemistry,” she explained.

“However, when a Netflix TV series that cast a black woman as Cleopatra was released, Egypt’s antiquities council was moved to make a statement that the depiction of Cleopatra as black is false. It is this kind of distancing of Egyptian history from its authentic African roots that has a strategic input for global power politics.”

An unrecognised past, an unfulfilling future

More than just breeding factual inaccuracies in textbooks, this denial of Africa’s influence on the development of modern society perpetuates the wholly inaccurate notion that the continent and its people lack history and therefore cannot contribute meaningfully to discussions that affect us.

What’s more, Ramphele said, Africans’ own failure to acknowledge this valuable inheritance and ensure that it is protected, celebrated and passed on to future generations will prevent us and others from seeing and appreciating our place in the web of life.

“At its time, Ancient Egypt was the most advanced civilisation, and it’s documented that the fathers of Western philosophy and science – people like Socrates, Plato, Archimedes and Aristotle – were educated by African priests. These things are, of course, never mentioned in ‘polite’ society and when they are, they are met with silent derision,” she said.

“To the extent that Africans do not learn African history beyond the revisionist colonial dogma created to justify European racist notions of our continent as a place without history. To that extent, our children and their children’s children will continue to live in ignorance of their great heritage.”

Reclaiming and reframing ancient knowledge

Speaking from her experience as an anti-apartheid activist and founding member of the BCM, Ramphele emphasised the significance not only of rejecting colonial narratives, but also of self-liberation.

“Black people in South Africa were kept in bondage for more than three-and-a-half centuries by a minority government representing less than 10% of the population. What my generation, in the 1960s reawakening, realised was that the most powerful weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressor,” she explained.

“We realised that it was our acquiescence to the oppressive colonial regime that we accepted as too powerful to defeat that was disabling us. Our ‘aha’ moment came when we focused our attention to the absurdity of accepting an imposed identity as the negative of one’s oppressor.

“We had accepted being referred to as non-Europeans; we were referring to ourselves as non-Europeans. And what chance do you have to challenge a system when you put the oppressor as the standard against which you are judged?”

Here, she noted, if future generations are to find their place in the world and change the narrative around Africa and Africans, we must reclaim African heritage as a foundation on which modern science has been built.

“We need to educate present and future generations of Africans to enable them to find their place on the map of human geography. We need to put to rest the colonial myth of Africa as the ‘dark continent’; the continent without history.

“Ancient African science is not just indigenous knowledge, as Westerners would like us to believe. Ancient African science is the beginning of wisdom and of modern sciences as we know them today.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.