‘It takes a child to raise a village’

29 July 2024 | Story Niémah Davids. Photos Robyn Walker. Read time 6 min.“The world is rife with formally declared and undeclared war on children. In these wars, adults kill children; it happens all over the world. Adults have always killed children. Very often the killing is direct and violent.”

When these killings happen, they are accompanied by “elaborate explanations and well-articulated arguments” of why it needed to be done. Often, those arguments seek to demonstrate that the children weren’t really the real targets. Instead, they just happened to be in the way or near adults who needed to be killed.

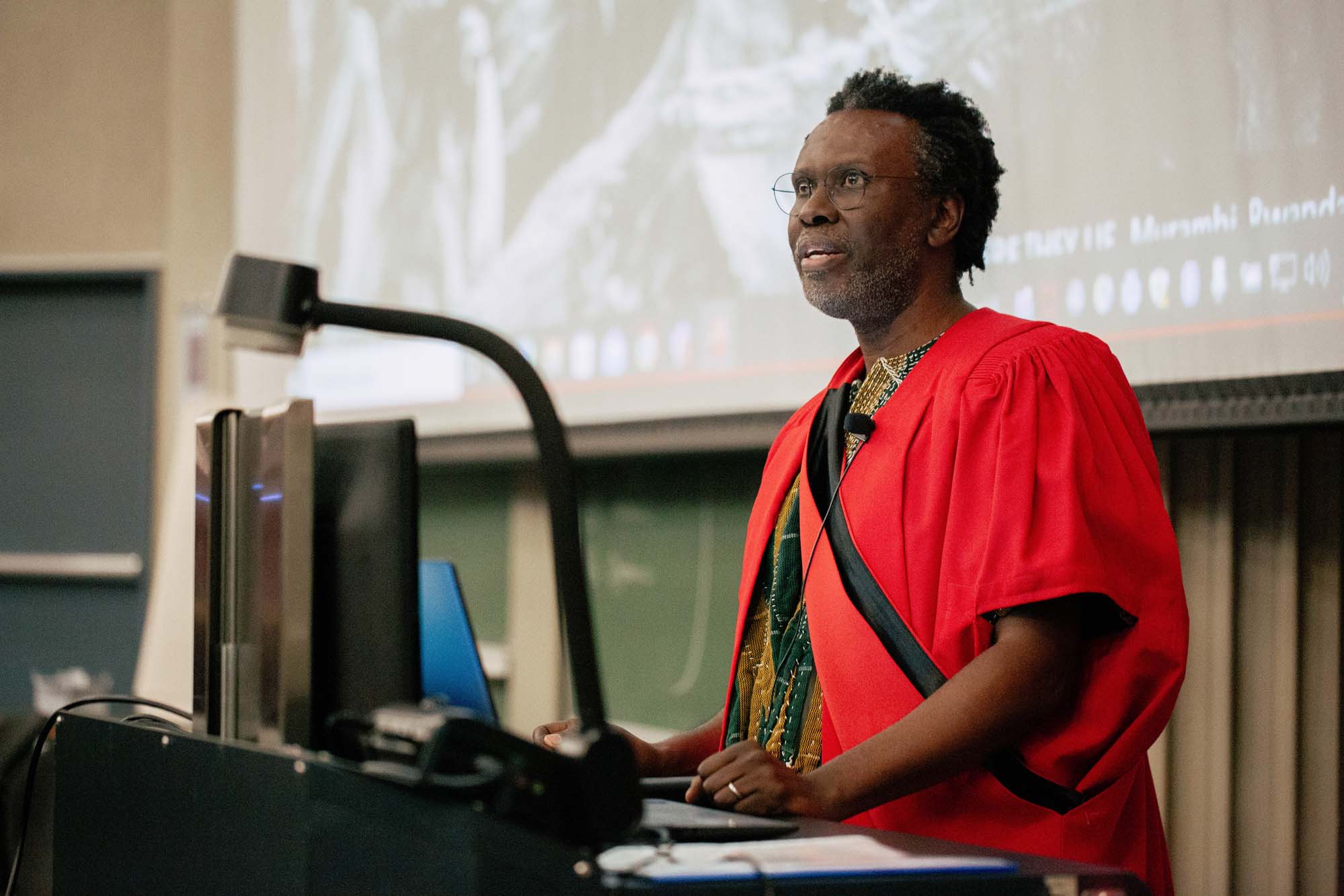

With these sobering words, the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Professor Rudzani Muloiwa kicked off his inaugural lecture on Thursday, 25 July. Professor Muloiwa is the head of the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at UCT and the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, and the co-director of the Vaccines for Africa Initiative (VACFA), whose home is located in the Faculty of Health Sciences.

Inaugural lectures celebrate academics’ scholarly work and their appointment to full professorship. Muloiwa’s lecture marked the seventh instalment of the university’s inaugural lecture series for 2024. The audience included an array of individuals in his circle, such as close family, friends, colleagues, mentors and mentees. UCT’s vice-chancellor designate, Professor Mosa Moshabela, was also in attendance.

Enemies, friends kill children

Muloiwa told the audience that children are killed because they are the offspring of their parents. And when this happens, he said, no explanations or justifications are necessary because the children “hold membership groups of people that need killing”.

More than that, he added, children are also killed due to neglect. And again, these killings are accompanied by well-articulated arguments about why it was unavoidable.

“This common and slow way [of killing] generally involves starvation and is generally more efficient in killing children. It has the added benefit of hardly attracting too much attention and thus making no one particularly accountable,” he said.

“Children are killed by enemies and friends, strangers and family.”

“Children are killed by enemies and friends, strangers and family. They’re killed by governments who their parents vote for over and over in every election. Most of these killings of children happen in Africa. Most people know this, including some Africans who care to know.”

A blind eye

Despite this ongoing massacre, Muloiwa said Africa has turned a blind eye.

“Whether we acknowledge this or not, it would seem that in Africa we’ve largely accepted this as the norm and our reality. We do not even count the number of our dead. If they are lucky, they get to be estimated,” he said.

Referencing the 1994 genocide in Rwanda, similarly, he said, the official number of estimated deaths of children back then range between 491 000 and 800 000. In stark contrast, some also estimate the number of dead to be as high as one million.

“This level of precision would make a mediocre statistician blush with embarrassment,” he said.

Crucially, he pointed out, that these estimates also fail to include the number of children permanently disabled during these violent and non-violent wars on children. This, Muloiwa added, begs the question: “Are we willing to accept this as our lot – the fate of our children?”

Take care of mothers

To ensure child well-being and build new realities for children, Muloiwa said it is crucial to involve all aspects and sectors of society in a meaningful way.

One thing is for sure, he said, it is impossible to keep children well and safe without taking care of their mothers. And considering the current South African context, where women are undervalued, achieving child well-being is impossible, Muloiwa noted. It’s also impossible to secure the well-being of mothers and children while neglecting the community, including families.

“As one of my [research] participants said, Sweden only turned around its child health outcomes when it invested into supporting struggling families. Unless this changes, children have no hope.”

The saying in reverse

While the saying “It takes a village to raise a child” has always resonated with Muloiwa, in recent times, in a “coherently interpreted society”, he said, the saying in reverse: “It takes a child to raise a village” is equally relevant and valid.

“Because if society starts to take the well-being of children seriously, it will have to change so much that the well-being of everyone will be accommodated. That’s just as simple as that.”

Undoubtedly, political will has a role to play too, and according to Muloiwa is critical in creating and growing an environment where child well-being is realised. This, he added, includes both active and passive political will. The importance here, he said, is for politicians to know when to “work positively towards realising child well-being”, and when not to “interfere too much” to allow others to get on with their work.

Ultimately, he reminded the audience that everything is connected.

What else it requires

Achieving child well-being also lies outside the confines of the healthcare sector.

“It would be absolutely foolish to try to improve the well-being of children by building more hospitals.”

“It would be absolutely foolish to try to improve the well-being of children by building more hospitals,” he said.

Again, he used high-income countries as an example. Muloiwa said those countries don’t offer good healthcare or achieve good health outcomes by building more hospitals. Instead, they achieve it by making a concerted effort to ensure that people don’t get sick.

“And so it is with child well-being.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

The UCT Inaugural Lecture Series

Inaugural lectures are a central part of university academic life. These events are held to commemorate the inaugural lecturer’s appointment to full professorship. They provide a platform for the academic to present the body of research that they have been focusing on during their career, while also giving UCT the opportunity to showcase its academics and share its research with members of the wider university community and the general public in an accessible way.

In April 2023, Interim Vice-Chancellor Emeritus Professor Daya Reddy announced that the Vice-Chancellor’s Inaugural Lecture Series would be held in abeyance in the coming months, to accommodate a resumption of inaugural lectures under a reconfigured UCT Inaugural Lecture Series – where the UCT extended executive has resolved that for the foreseeable future, all inaugural lectures will be resumed at faculty level.

Recent executive communications

2025

2024

Professor Susan Cleary delivered her inaugural lecture on 14 March.

14 Mar 2024 - 5 min read2023

Prof Lydia Cairncross’s inaugural lecture provided a snapshot of the career path of a surgeon and community activist whose commitment to social justice means her work doesn’t end in the operating theatre.

02 Nov 2023 - 8 min read2022

Professor Linda Ronnie is in UCT’s Faculty of Commerce.

28 Sep 2022 - 6 min read2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016 and 2015

No inaugural lectures took place during 2015 and 2016.

.jpg)