UCT celebrates International Mother Language Day to announce new language policy

11 March 2025 | Story Myolisi Gophe. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 6 min.

In a country where language barriers have long hindered access to critical services, the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) recent celebration of International Mother Language Day marked a significant milestone. The event on Thursday, 27 February, not only served as a platform to announce UCT’s new language policy, approved by Council in December 2024, but also reinforced the university’s commitment to multilingualism.

While International Mother Language Day is globally observed on 21 February, UCT scheduled its event later to avoid competing with national celebrations, which many university members are required to attend. According to Associate Professor Lolie Makhubu-Badenhorst, the director of the Multilingualism Education Project (MEP), this timing ensured broader participation and engagement.

Grounded in constitutional and institutional commitments

The adoption of the new language policy aligns with the South African Constitution, which guarantees the right to education in one’s preferred language where reasonably practicable. It also complies with the Department of Higher Education and Training’s (DHET) New Language Policy Framework, which mandates universities to develop strategies for multilingualism in teaching, learning, research, and communication, Associate Professor Makhubu-Badenhorst explained.

Furthermore, the policy supports UCT’s Vision 2030, which embraces linguistic and cultural diversity to make meaningful contributions to the African continent. Under this framework, UCT has officially adopted English, isiXhosa, and Afrikaans as its three primary languages, while also recognising the importance of Kaaps, South African Sign Language (SASL), Khoekhoe, and other languages. Institutional funding and resources will be allocated to developing these languages and integrating them into various aspects of university life.

“It was not easy to finalise the policy; it felt almost impossible at times.”

The policy and its implementation come as a perfect response from UCT to the United Nations General Assembly declaration of the period between 2022 and 2032 as the International Decade of Indigenous Languages. This draws attention to the critical status of many indigenous languages across the world and encourages action for their preservation, revitalisation and promotion.

While Makhubu-Badenhorst and her team will be lending a helping hand to the university community for the implementation of policy at faculty levels in teaching and learning, as well as in professional, administrative and support service levels, she advised that the process should be undertaken in baby steps.

A step-by-step implementation approach

Makhubu-Badenhorst said that while the policy’s approval was a significant achievement, its implementation must be gradual and inclusive.

“It was not easy to finalise the policy; it felt almost impossible at times. In fact, the first submission to Council was sent back for revision. But I’m pleased to announce that it was unanimously accepted.”

In his welcome address, Professor Brandon Collier-Reed, UCT’s deputy vice-chancellor for Teaching and Learning, congratulated and commended Makhubu-Badenhorst for working tirelessly to ensure that the policy gets approved. “You can see why it so important for the university to finalise this policy. It gives us the licence to implement multilingualism across the university and make the change that we so desperately need to recognise multi cultures available on our campus. Multilingualism is the strength to harness diversity.”

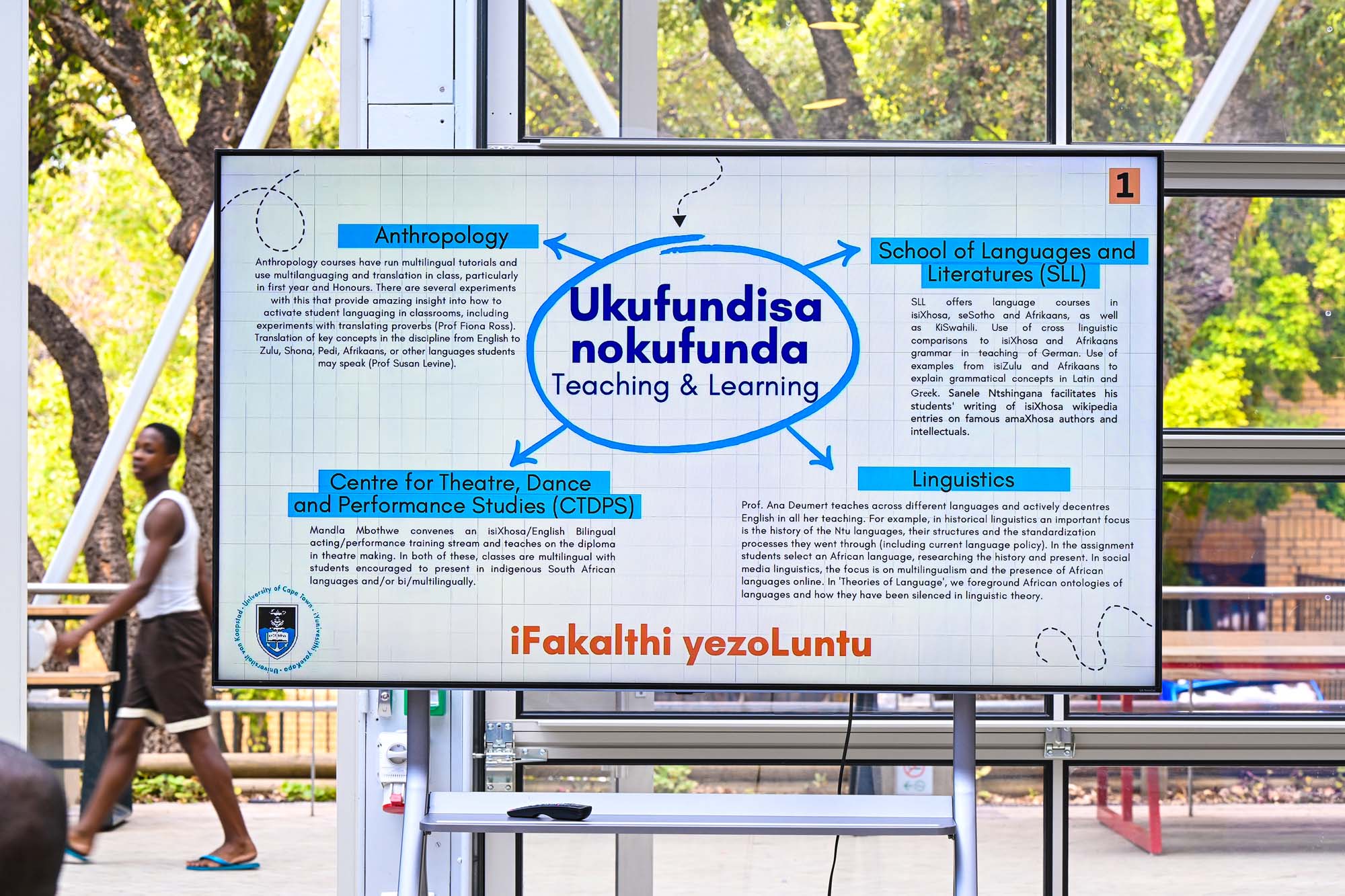

Departments leading the way

While the university is gearing up for full implementation, several departments have already made strides in embracing multilingualism. Professor Carolyn McKinney from the School of Education highlighted them:

- The Centre for Theatre, Dance and Performance Studies students are writing and performing in isiXhosa

- African Languages students have to contribute to isiXhosa Wikipedia by write entries of famous intellectuals

- Sociology students are introduced to relevant concepts in isiXhosa and isiXhosa text written in the late 1800s, and conducted isiXhosa intellectual research project

- Historical Studies use of historic texts written in isiXhosa with English translations in a range of courses.

- the Umthombo Centre make use of multilingual essay writing and glossary of terms while guest speaker facilitating multilingualism in class and course reading

- The South African College of Music opera with libretto written in isiXhosa and postgraduate students encouraged to write their dissertation partly in an African language

- In the Centre for Film and Media Studies, Professor Adam Haupt is collaborating with the Centre for Multilingualism and Diversity Research at the University of the Western Cape on the first trilingual dictionary of Kaaps, and

- School of Education’s language-for-learning research project on bi/multilingual strategies for teaching science, mathematics and English in isiXhosa and English.

“We are doing it but not every day. The challenge to implement multilingual policy is to think about our need to ‘demonolingualising’ the space. We often talk about multilingual, but we don’t talk about what is it against; the power dynamics involved. It’s not about the policy or the senior executive but it’s about everyone in the university community embracing diversity and making multilingualism happen.”

As the university looks to embark on the implementation phase of the new language policy, the process sparked vibrant discussions, with panellists and audience members offering practical solutions.

Among them was Juan Steyn of the South African Centre for Digital Language Resources (SADiLAR) – a national centre that supports research and development in the domains of language technologies and language-related studies in the humanities and social sciences. The centre supports the creation, management and distribution of digital language resources.

Disability Advocacy specialist Lesego Modutle and Sign Language interpreter Asanda Katshwa warned that multilingualism will not be complete if Sign Language users are left behind. They said although Sign Language was made the 12th official language in South Africa last year, education for Deaf people is still a huge challenge.

“There are Sign Language interpreters that you can tap into,” Modutle noted. “Teach yourselves how to work with them and understand that they are there as a way of communication and not to replace a hearing person. I’m sure many of us could know people in our communities that are Deaf, but we are too scared to approach them because the unknown is scary. Approach that person and they will teach you. The best way to learn a language is by learning it from the user themselves. I’m so proud of UCT because we are moving towards the right direction.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.