Upgrades to informal settlements urgently needed

03 April 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Read time >10 min.

Khayelitsha is one of the many townships in South Africa established as a racially segregated residential area under the apartheid regime. Like most areas established for “black Africans” during apartheid, it exists on the periphery of the city, some 39 km from Cape Town’s centre.

About 10 years ago, Khayelitsha represented the largest concentration of poverty in the highly unequal city of Cape Town. The majority (54.5%) of its households lived in informal dwellings and, as a health sub-district, Khayelitsha reported the worst health indicators in the city.

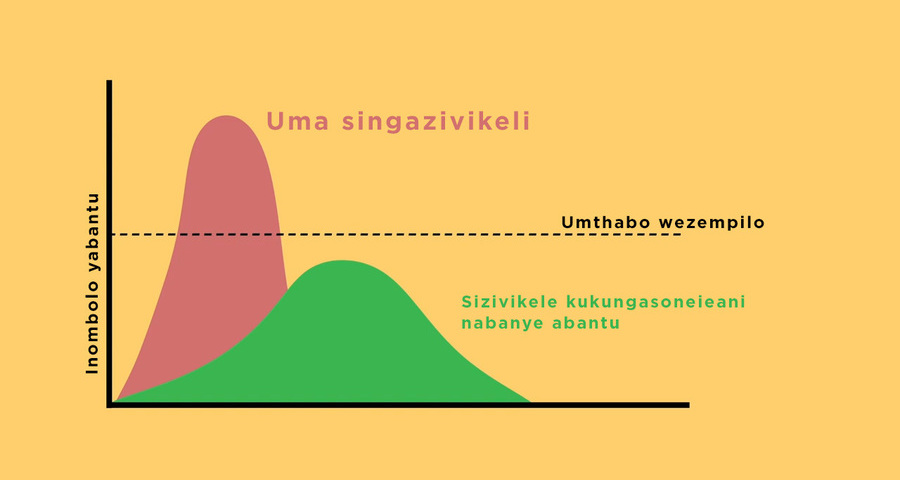

At the time of writing, two individuals in Khayelitsha have tested positive for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). It is, arguably, cause for concern. Residents in informal settlements and townships are particularly at risk from infectious diseases as it is difficult to practise preventive measures such as social distancing in overcrowded conditions. There’s also a lack of adequate water supply and sanitation, which means practising good hygiene is extremely difficult.

As the nation began its 21-day lockdown at midnight on 26 March, the South African government was quick to respond to some of the challenges faced in informal settlements in areas like Khayelitsha. Interventions have included the provision of emergency water supplies, such as water storage tanks and water tankers, as well as the identification of sites for people who cannot self-isolate at home. But what the COVID-19 pandemic has brought to the fore, and which must be tackled with urgency, is the upgrading of informal settlements.

This is the position of Dr Warren Smit, the manager of research at the African Centre for Cities (ACC), an interdisciplinary urban research institute at the University of Cape Town (UCT). Smit is an urban planner by background and his main areas of research are cities in Africa, urban governance, urban health and informal settlements.

Burdens of disease

Ironically, the roots of racially segregated residential areas in Cape Town, such as Khayelitsha, date back to 1901, when there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the city. The Cape Town Council “decided that a location should be built so that Africans could be housed under controlled and sanitary conditions”, and black African residents were forcibly relocated to the newly established segregated township of Ndabeni, which was on the periphery of the city at the time.

Today, cities in the global south, like Cape Town, are characterised by particularly large and complex healthcare burdens. This is made up of infectious diseases; non-communicable or chronic diseases (NCD); injuries; mental health-related issues, such as psychosocial stress and depression; and substance abuse.

NCDs, such as diabetes mellitus and ischaemic heart disease, are growing rapidly in the global south as a result of changed diets and lifestyles associated with urbanisation, explained Smit. But levels of infectious disease also remain high.

“Urban environments have a profound impact on human health.”

There are two broad types of infectious disease. The first type is associated with poor environmental conditions and includes diarrhoea, respiratory illnesses and malaria. The second type is associated with person-to-person transmission, which includes tuberculosis, HIV and AIDS, and COVID-19.

In informal settlements, problems of insecurity of tenure, poor shelter, overcrowding, lack of services and hazardous location all intersect to create particularly large and complex burdens of disease, explained Smit.

Analysis of Cape Town data on the “average age-standardised mortality rates per 100 000 people” highlights the enormous differences between the Khayelitsha sub-district and other parts of Cape Town, such as the South Peninsula sub-district. Between 2001 and 2006, for NCDs, Khayelitsha recorded a rate of 844, the South Peninsula 526 and Cape Town 618. For HIV and AIDS, the rates in respective order were 229, 30 and 79. For other communicable diseases, Khayelitsha recorded 321, the South Peninsula 82 and Cape Town 135.*

As Smit explained, “urban environments have a profound impact on human health”.

Lived realities

Currently, residents in informal settlements face a multitude of social, economic and political factors that shape their built environment and have negative impacts on their health and well-being.

One of the realities of life in Khayelitsha and in similar communities, is “high food insecurity and low dietary diversity”. In a 2016 paper on Khayelitsha, Smit and his co-authors highlighted how difficult it is for many residents to access enough healthy and nutritious food. While spaza shops and roadside informal traders provide residents with smaller, ad hoc purchases, they do not suffice for major shopping trips, which are usually made on a weekly or monthly basis.

Smit and his colleagues’ research shows that for major shopping trips, residents must often walk 25 or 30 minutes to the closest mall or travel there by train and taxi. With the nationwide lockdown, the ability of residents to continue doing so is limited.

Food security in informal settlements is further complicated by a lack of access to electricity. In households where there is no connection to electricity, keeping perishable food fresh requires alternative strategies, including illegally procuring electricity, storing food in a neighbour’s fridge or in buckets. All alternatives present their own challenges, such as the potential for conflict if food goes missing at a neighbour’s home or attracting rodents that will destroy the buckets and eat the food.

In addition, informal settlements are often not conducive to safe physical activity; they are sometimes far from community facilities such as clinics; and residents’ mental health can be impacted by factors such as crime, poverty and unemployment.

Overcrowding and density

Overcrowding is also a major concern in informal settlements. The problem of overcrowding, however, is not limited to informal settlements, explained Smit. Formal housing can be, and often is, also overcrowded.

Here, Smit pointed out that it is important not to conflate overcrowding and density. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme defines overcrowding as “more than three people per habitable room of a dwelling”. In situations where there is overcrowding, rapid transmission of infectious diseases can occur between people and can also have negative impacts on mental health.

Density, on the other hand, is measured by the number of dwelling units per hectare. Smit explained that it has been estimated that at least 25 to 50 dwelling units per hectare across a city is necessary for viable public transport.

“Denser and more compact cities are usually also safer and more sustainable and offer easier access for residents to employment opportunities and a range of facilities,” said Smit.

“It is possible to densify a city while simultaneously reducing overcrowding.”

He said that while figures vary considerably, Cape Town seems to have an average density of far fewer than 25 dwelling units per hectare.

“The sprawling, low-density nature of the city particularly impacts on low-income residents who have to spend an enormous amount of time and money on travel.”

Thus, higher densities are good for cities, and making low-density cities denser and more compact is an important tool for urban planning.

However, said Smit, overcrowding is bad and needs to be eliminated through ensuring that all households have sufficient space. This can be achieved through support for extending existing dwellings, where possible, or through the provision of well-located affordable housing of sufficient size.

“It is possible to densify a city while simultaneously reducing overcrowding,” he said.

Healthy planning

If done right, urban planning can play an important role in achieving healthy urban environments. Healthy urban planning includes ensuring access to adequate shelter, water supply and sanitation; creating urban environments conducive to healthy diets, physical activity, safety and good mental health; and ensuring urban development does not negatively impact on the natural environment (water, air, ecosystems).

While all of this cannot be achieved in the short term, and certainly not during the lockdown, there are tools that stakeholders can begin to consider and use to answer the urgent need for upgrading informal settlements and making our cities healthier.

“Public health regulations have frequently been used to demolish ‘slums’ and relocate residents in the name of better health,” said Smit. “Often, however, residents relocated end up worse off, further away from employment opportunities and facilities, and with their social networks severely disrupted.”

“Often, however, residents relocated end up worse off, further away from employment opportunities and facilities.”

Therefore, the ACC researcher advised that attempts to “de-densify” overcrowded settlements must be done “carefully and only where absolutely necessary, with extensive participation by residents, in order to avoid making people more vulnerable and at risk”.

He also suggested that projects to upgrade informal settlements and provide residents with adequate living space and services such as water and sanitation need to be participatory. These must also be accompanied by a range of social and economic development programmes to improve people’s lives and reduce their vulnerability to risks.

Smit’s final suggestion for upgrading informal settlements – because there are also many vulnerable people living in overcrowded conditions in formal townships and new “Reconstruction and Development Programme” housing areas – is that it is equally important to have social and economic development programmes in these areas.

*Groenewald, P; Bradshaw, D; Daniels, J; Zinyakatira, N; Matzopoulos, R; Bourne, D; Shaikh, N; and Naledi, T (2010). “Local-level mortality surveillance in resource-limited settings: A case study of Cape Town highlights disparities in health”. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 88(6), 444–451.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 updates

COVID-19 is a global pandemic that caused President Cyril Ramaphosa to declare a national disaster in South Africa on 15 March 2020 and to implement a national lockdown from 26 March.

UCT is taking the threat of infection in our university community extremely seriously, and this page will be updated regularly with the latest COVID-19 information. Please note that the information on this page is subject to change depending on current lockdown regulations.

Frequently asked questions

Daily updates

Campus communications

2020

Resources

Video messages from the Department of Medicine

Getting credible, evidence-based, accessible information and recommendations relating to COVID-19

The Department of Medicine at the University of Cape Town and Groote Schuur Hospital, are producing educational video material for use on digital platforms and in multiple languages. The information contained in these videos is authenticated and endorsed by the team of experts based in the Department of Medicine. Many of the recommendations are based on current best evidence and are aligned to provincial, national and international guidelines. For more information on UCT’s Department of Medicine, please visit the website.

To watch more videos like these, visit the Department of Medicine’s YouTube channel.

Useful information from UCT

External resources

News and opinions

As the COVID-19 crisis drags on and evolves, civil society groups are responding to growing and diversifying needs – just when access to resources is becoming more insecure, writes UCT’s Prof Ralph Hamann.

03 Jul 2020 - 6 min read Republished

The Covid-19 crisis has reinforced the global consequences of fragmented, inadequate and inequitable healthcare systems and the damage caused by hesitant and poorly communicated responses.

24 Jun 2020 - >10 min read Opinion

Our scientists must not practise in isolation, but be encouraged to be creative and increase our knowledge of the needs of developing economies, write Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng, vice-chancellor of UCT, and Professor Thokozani Majozi from the University of the Witwatersrand.

09 Jun 2020 - 6 min read Republished

South Africa has been recognised globally for its success in flattening the curve, which came as a result of President Ramaphosa responding quickly to the crisis, writes Prof Alan Hirsch.

28 Apr 2020 - 6 min read RepublishedStatements and media releases

Media releases

Read more

Statements from Government

In an email to the UCT community, Vice-Chancellor Professor Mamokgethi Phakeng said:

“COVID-19, caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2, is a rapidly changing epidemic. [...] Information [...] will be updated as and when new information becomes available.”

We are continuing to monitor the situation and we will be updating the UCT community regularly – as and when there are further updates. If you are concerned or need more information, students can contact the Student Wellness Service on 021 650 5620 or 021 650 1271 (after hours), while staff can contact 021 650 5685.