Revolution at SA campuses

11 May 2002

Despite a dramatic student "Africanisation" of South African universities and technikons from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, a closer look reveals that this revolution has come with its own set of twists.

DESPITE a dramatic student "Africanisation" of South African universities and technikons from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, a closer look reveals that this revolution has come with its own set of twists.

This according to Associate Professor Dave Cooper of the Department of Sociology in his new book, The Skewed Revolution – Trends in South African Higher Education: 1988–1998, which he co-authored with Associate Professor George Subotzky, Director of the Education Policy Unit (EPU) at the University of the Western Cape. In this volume, published by the EPU with a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cooper takes a statistical look at the increase in African students registering at the 21 universities and 15 technikons around the country.

In contrast, the six HAUs 9like Fort Hare, the Universities of the North and Transkei) had experienced a big drop in numbers around 1994/1995 after an initial and sharp increase in the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

"There is some transfer to historically white universities, but students also just leaving – some are just not going to universities, it seems," notes Cooper.

Dividing Historically White Universities (HWUs) into Afrikaans and English institutions, the book shows that from the mid-1990s Afrikaans universities have absorbed greater numbers of African students, albeit mostly into distance learning. "The four historically English universities are slowly increasing Africanisation, but not nearly as dramatically as the Afrikaans universities."

The biggest changes have come at technikons however, Cooper argues. The analysis also divided these institutions into Historically African Technikons (HATs) (e.g. Eastern Cape, Border Technikons) and Historically Non-African Technikons (HNATs) (including Peninsula Technikon).

According to Cooper, there has been some increase of African students at the HATs. "But the real big changes are at the seven Historically White Technikons (HWTs)," he says.

"The HWTs shifted from about 2% African in 1988 to about 53% as a group 10 years later. This is what I call a main point of the revolution."

But it's a lopsided revolution, notes Cooper. Most African university and technikon students are not going into science and technology, a trend Cooper ascribes to a poor mathematics preparation at school.

Even in commerce – a more popular option among African students – they are often sticking to the fringe areas such as public relations and human resources. This may again be because of a poor maths grounding among other reasons.

Interestingly, women now nearly outnumber their male counterparts among all racial groupings, Cooper points out. "But again, they don't often go into sciences, with the exception of Indian women," he adds.

In their conclusion, the two authors note that there has been a massive increase in African students, but that they have been leaving the historically African institutions – such as Fort Hare – and moving to HWUs. "We also suggest that this Africanisation of universities and technikons wasn't actually planned by the government."

Not that the state didn't want this to happen, but the influx of students may have more to do with a "grassroots" move inspired by parents and families, who encourage their children to go to universities and technikons. Cooper also argues that, like the events described in EP Thompson's The making of the English working class, there currently exists a process that's creating an African middle class.

"But you're not seeing the making of an African upper-middle class, because students are not going into accountancy or architecture or fields where at least some postgraduate studies are required. There is the making of a small upper-middle class of Africans in parliament and business, but not in the professions."

According to Cooper, The Skewed Revolution aimed to provide more than just a cursory view of the "Africanisation" of tertiary education. "It's a very fine breakdown," he says.

"You can't know what's going on in higher education with a very broad overview. You've got to dig down."

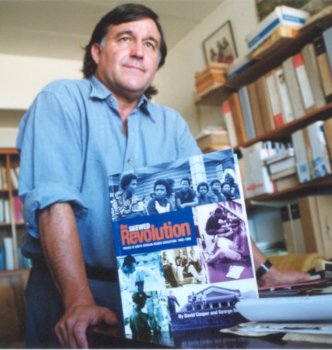

Student revolution: Professor David Cooper's new book, The Skewed Revolution, shows that the immigration of African students in tertiary education is not as straightforward as it seems at first glance.

DESPITE a dramatic student "Africanisation" of South African universities and technikons from the late 1980s to the late 1990s, a closer look reveals that this revolution has come with its own set of twists.

This according to Associate Professor Dave Cooper of the Department of Sociology in his new book, The Skewed Revolution – Trends in South African Higher Education: 1988–1998, which he co-authored with Associate Professor George Subotzky, Director of the Education Policy Unit (EPU) at the University of the Western Cape. In this volume, published by the EPU with a grant from the Ford Foundation, Cooper takes a statistical look at the increase in African students registering at the 21 universities and 15 technikons around the country.

"There is some transfer to historically white universities, but students also just leaving – they're not going to universities."To this end, the Cooper looked at the 10 Historically Black Universities (HBUs), breaking these down into six Historically African Universities (HAUs), two Historically Non-African Universities (HNAUs) and two "special cases" (Medunsa and Vista University). He found, firstly, that at the two HNAU – the University of Durban-Westville (UDW) and the University of the Western Cape (UWC) – there had been a "massive" change from coloured/Indian students to African students in the 1990s.

In contrast, the six HAUs 9like Fort Hare, the Universities of the North and Transkei) had experienced a big drop in numbers around 1994/1995 after an initial and sharp increase in the late 1980s and the early 1990s.

"There is some transfer to historically white universities, but students also just leaving – some are just not going to universities, it seems," notes Cooper.

Dividing Historically White Universities (HWUs) into Afrikaans and English institutions, the book shows that from the mid-1990s Afrikaans universities have absorbed greater numbers of African students, albeit mostly into distance learning. "The four historically English universities are slowly increasing Africanisation, but not nearly as dramatically as the Afrikaans universities."

The biggest changes have come at technikons however, Cooper argues. The analysis also divided these institutions into Historically African Technikons (HATs) (e.g. Eastern Cape, Border Technikons) and Historically Non-African Technikons (HNATs) (including Peninsula Technikon).

According to Cooper, there has been some increase of African students at the HATs. "But the real big changes are at the seven Historically White Technikons (HWTs)," he says.

"The HWTs shifted from about 2% African in 1988 to about 53% as a group 10 years later. This is what I call a main point of the revolution."

But it's a lopsided revolution, notes Cooper. Most African university and technikon students are not going into science and technology, a trend Cooper ascribes to a poor mathematics preparation at school.

Even in commerce – a more popular option among African students – they are often sticking to the fringe areas such as public relations and human resources. This may again be because of a poor maths grounding among other reasons.

Interestingly, women now nearly outnumber their male counterparts among all racial groupings, Cooper points out. "But again, they don't often go into sciences, with the exception of Indian women," he adds.

In their conclusion, the two authors note that there has been a massive increase in African students, but that they have been leaving the historically African institutions – such as Fort Hare – and moving to HWUs. "We also suggest that this Africanisation of universities and technikons wasn't actually planned by the government."

Not that the state didn't want this to happen, but the influx of students may have more to do with a "grassroots" move inspired by parents and families, who encourage their children to go to universities and technikons. Cooper also argues that, like the events described in EP Thompson's The making of the English working class, there currently exists a process that's creating an African middle class.

"But you're not seeing the making of an African upper-middle class, because students are not going into accountancy or architecture or fields where at least some postgraduate studies are required. There is the making of a small upper-middle class of Africans in parliament and business, but not in the professions."

According to Cooper, The Skewed Revolution aimed to provide more than just a cursory view of the "Africanisation" of tertiary education. "It's a very fine breakdown," he says.

"You can't know what's going on in higher education with a very broad overview. You've got to dig down."

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.