Negotiating the fabric of the African university: UCT hosts second session of three-day conference

21 September 2023 | Story Maya Skillen. Photos Je’nine May. Read time 7 min.

On Wednesday, 13 September, the Institute for Humanities in Africa (HUMA) welcomed local and international scholars to discuss the response of African universities to the drive towards a global standardisation of higher education models, as part of a conference, titled “Negotiating the Fabric of the African University”.

HUMA, which is based in the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Cape Town (UCT), hosted day two of the three-day event, while the University of the Western Cape hosted the first day, and Stellenbosch University the third. The conference was partially funded by the Volkswagen Foundation and jointly organised by representatives of the three South African universities, in association with partners from the University of Bonn, Germany; and the Goethe Institute in Johannesburg.

The conference explored the global trends shaping African universities in relation to teaching and learning, research and innovation, governance and more; and the character of the African university that will emerge because of these influences, taking into account difficult political and economic conditions as well as concerns around quality, diversity, employability and decolonisation agendas.

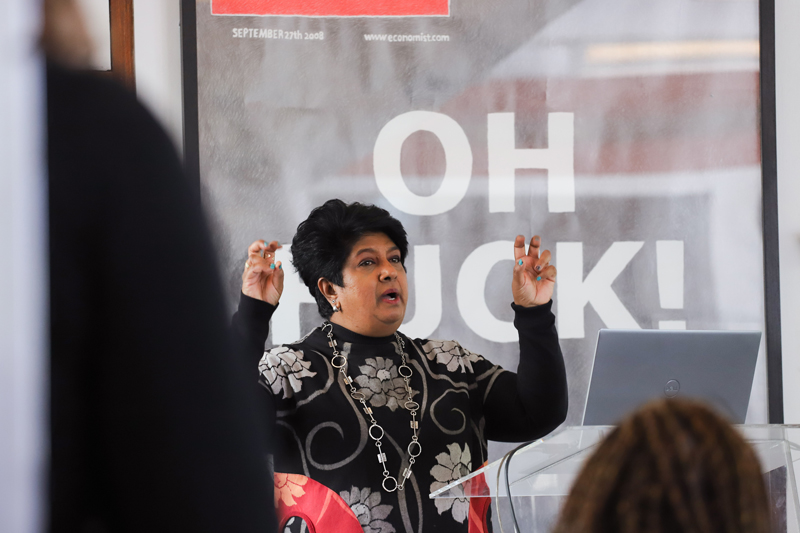

The morning session’s main presentation was a keynote address, titled “Emerging operating modes in African universities: Innovations in teaching, research and community engagement” by Dr Teboho Moja, a professor of higher education at New York University, an extraordinary professor at the University of the Western Cape, and a visiting research fellow at the University of Pretoria. This was bookended by a series of introductory talks and a round-table discussion on issues of governance.

Introductory talks

“Is this a university in Africa, or an African university?” asked Associate Professor Kasturi Behari-Leak, the dean of the Centre for Higher Education Development (CHED) at UCT, in her presentation, which spotlighted the importance of negotiating and reinvestigating matters relating to heritage, the true purpose of a university, the structure of learning, the colonial gaze and more. “A possible danger of being a university in Africa is the transportation of everything that is global and northern into a location that is geographically south; but being an African university might mean that we have to reimagine and reinvent – but also reassert – what it means to be African at this moment in time.”

Daniel Munene of UCT’s Commerce Education Development Unit recollected how kiSwahili came to be incorporated as a language of study at UCT, the seeds of which were planted partially during the upwelling of discussions on decoloniality in 2015 and 2016; while the director of the School of Education, Azeem Badroodien, pointed out that higher education is always moving and being reshaped, and that it “lives in a place of conflict, not in an ivory tower”. Professor Shose Kessi, the dean of the Faculty of Humanities, focused her talk on the university as a site of protest – where coloniality was challenged, in Africa and in the United States, in the wake of the civil rights movement – and the negative impact of the commodification of higher education.

Keynote address

Dr Moja centred her lecture on three elements: internationalisation and collaboration in the African context; emerging modes of operation, driven by innovations in teaching, research, and community engagement; and how universities are responding to funding challenges.

“I consider myself an Afro-optimist,” she said. “I believe our universities are building the Africa we want. [I hope to demonstrate that] our universities are not mere victims of colonisation, as they emerge out of that legacy and transform the systems as well as the students that go through them.”

Internationalisation is an essential component of the strategy of African universities, Moja said, because as they seek to expand their global reach or gain visibility, they collaborate in knowledge production, and so enhance their educational offerings. Moja also found that internationalisation in the African context is usually aligned with the achievement of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals and the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

“African universities are contributing to the attainment of socio-economic, environmental and cultural objectives,” she said. “By aligning their efforts with national, regional and global development agendas, they are well positioned to address the unique challenges facing the continent and contribute to its sustainable development.”

The incorporation of indigenous knowledge systems into curricula and the establishment of centres to deepen this drive is an emerging mode of operation that African universities are adopting, as are efforts to build capacity and skills development. Redefining community engagement, in which knowledge is co-shared, is another mode of operation, where many institutions are establishing partnerships and projects with community organisations, governmental agencies and industry stakeholders to address community concerns.

“Universities are undergoing a transformation in their approach to community engagement, recognising its pivotal role in fostering positive social change and contributing to sustainable development,” Moja said.

African higher education institutions are having to find innovative ways to address a lack of financial resources. In South Africa, she said, there has been an increase in third-stream funding, where universities are engaged in income-generating activities. Increasingly, universities are also offering consulting services, as well as setting up endowments – a common practice in the Global North, but something that is new to universities on the continent, as it differs from African forms of philanthropy.

Despite the challenges, “universities in Africa are actively planting the seeds of change,” Moja concluded.

Round table

A round table on governance at higher education institutions closed the morning session, and featured the work of four academics. Professor Emnet Tadesse Woldegiorgis of the Ali Mazrui Centre for Higher Education Studies at the University of Johannesburg began with a critical reflection on neoliberalism and the decline of African scholarship. This was followed by a presentation by Dr Aretha Asakitikpi of the Southern Business School, also in Johannesburg, on fostering innovation and creativity in African universities. Valentine Ubanako offered insight into local solutions to challenges in teaching and learning at the University of Yaounde 1 in Cameroon, where he is based; and his colleague Professor Stephen A Mforteh presented the findings of a study that investigated pooling the scientific capacities of the University of Yaounde 1 with those of research institutes.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Centre for Higher Education Development

In the news

.jpg)