#MustFall movements were ‘an act of love’

23 May 2019 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Michael Hammond. Read time 6 min.

The Rhodes Must Fall (RMF) and Fees Must Fall (FMF) protests, collectively known as the #MustFall movements, were a warning sign that conditions in South Africa must change for the better. If not, continued unrest remains on the cards for higher education institutions across the country. But what is important is that the movements were also born from love.

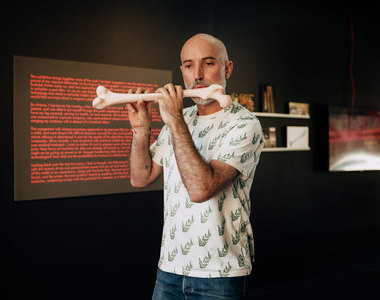

University of Cape Town (UCT) and University of Oxford alumnus, author and political commentator Rekgotsofetse Chikane delivered this view during a conversation at the Graduate School of Business (GSB) on 21 May.

He was in conversation with GSB senior lecturer, award-winning author and poet Athol Williams. Their talk centred around Chikane’s debut book, Breaking a Rainbow, Building a Nation: The politics behind #MustFall movements.

“Fees was a proxy, a very tangible proxy, to say that the status quo of the country has to change.”

The two used the book as a springboard to unpack the #MustFall movements, in which Chikane was a prominent figure. He provided insight into what drove the protests, their tie-in with youth politics in general and the larger political context, and weighed in on the violence that occurred at the time.

“Fees was a proxy, a very tangible proxy, to say that the status quo of the country has to change,” he said.

“The previous democratic processes … made available to us to change this country, over the past 20-plus years, have clearly failed. There [are] no two ways to interpret that.”

Changing strategies and tactics

Student leaders across the country were consistently and frustratingly finding themselves hitting the same “roadblock” when trying to resolve the fees challenge at universities. They realised their strategies and tactics needed to change.

He described this as an “evolution of youth politics”, of youth unrest and a “powerful demonstration of what resistance means”.

“This is an inevitability unless something changes,” he said.

The #MustFall movements were also about building consciousness.

“It was an act of love,” said Chikane.

It was about black students not feeling welcome and enabled on the country’s campuses, particularly at historically white universities, he explained. It was about fighting that feeling and the structures and systems that oppress and isolate black students. But it was also about owning their story.

“The knowledge from the get-go was ‘we are in a special moment, we’re about to tell our own stories’.”

But there was the realisation that their story could not yet be owned because they didn’t know enough about their own history. Resolving this through intensive reading was an important part of RMF and FMF.

“The knowledge from the get-go was ‘we are in a special moment, we’re about to tell our own stories’.”

From this point of knowing themselves and their history, students were better equipped: They realised they were, in fact, special and that they do belong. Instead of breaking themselves down, they decided they needed to “break down what inhibits us [in] one way or another”.

“And I think there is a beauty in breaking things especially if there are good … outcomes. However, there [were] unintended consequences,” said Chikane.

On violence

Violence is an inescapable truth of the #MustFall movements and Chikane was asked to explain students’ use and experience of it, particularly as it plays out in a democracy.

He referred again to the need for a change in strategy and tactics. Students realised they were “not negotiating from a position of strength”. Therefore, there was a decision that in certain circumstances, symbolic violence was necessary.

But even symbolic violence – which included demanding that University of the Witwatersrand Vice-Chancellor Adam Habib sat on the ground with the students – was weakened in effect.

The students felt that the status quo would not change “if we ask you nicely”. But, said Chikane, they did not only enact violence; they responded to it too.

“There is this implicit judgement placed on the protesters that they are the ones that became violent,” he said, naming media as being guilty of painting students as perpetrators.

And while Chikane felt that violence, symbolic or otherwise, had been a catalyst for change, he stressed that it should not be necessary, and that the conditions that make it inevitable must be resolved and avoided.

“We can turn to violence in a manner that causes change, but we shouldn’t have to turn to violence,” he said.

“Don’t create the situation where you have pushed us into a far corner.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.