The Trojan Horse Massacre: ‘We had stones; they had bullets’

15 October 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Journalists Aamirah Sonday and Carla Bernardo. Camerawork Mad Little Badger. Video Edit Mad Little Badger. Voice Lerato Molale. Read time 8 min.

This is the first of two articles by UCT News, which commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Trojan Horse Massacres.

Tuesday, 15 October 1985. A joint task force, organised by the National Joint Operational Centre (JOC), sent a decoy truck into Athlone, Cape Town. The truck was painted orange, and at the back of the truck, hidden in wooden crates, were members of the apartheid security police, the South African Defence Force and the railway police.

The orange truck drove down one of the suburb’s main roads as workers were making their way home, children were playing outside and mothers were hanging up the day’s washing. The orange truck made its way back up Thornton Road and, on seeing this railway truck, a symbol of an oppressive regime, youth nearby began throwing stones.

“That was our weapon – stones. They had bullets; they had lethal ammunition,” said University of Cape Town (UCT) alumnus, anti-apartheid activist and uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) veteran Shirley Gunn.

And that’s all that was needed – for stones to hit the decoy truck. The task force members sprang up from their wooden crates and opened fire. There were no warning shots. No tear gas. They responded to stones being thrown with live ammunition.

“If you know who holds a firearm and discharges a bullet, you will know who killed those boys. Nobody was [found] culpable.”

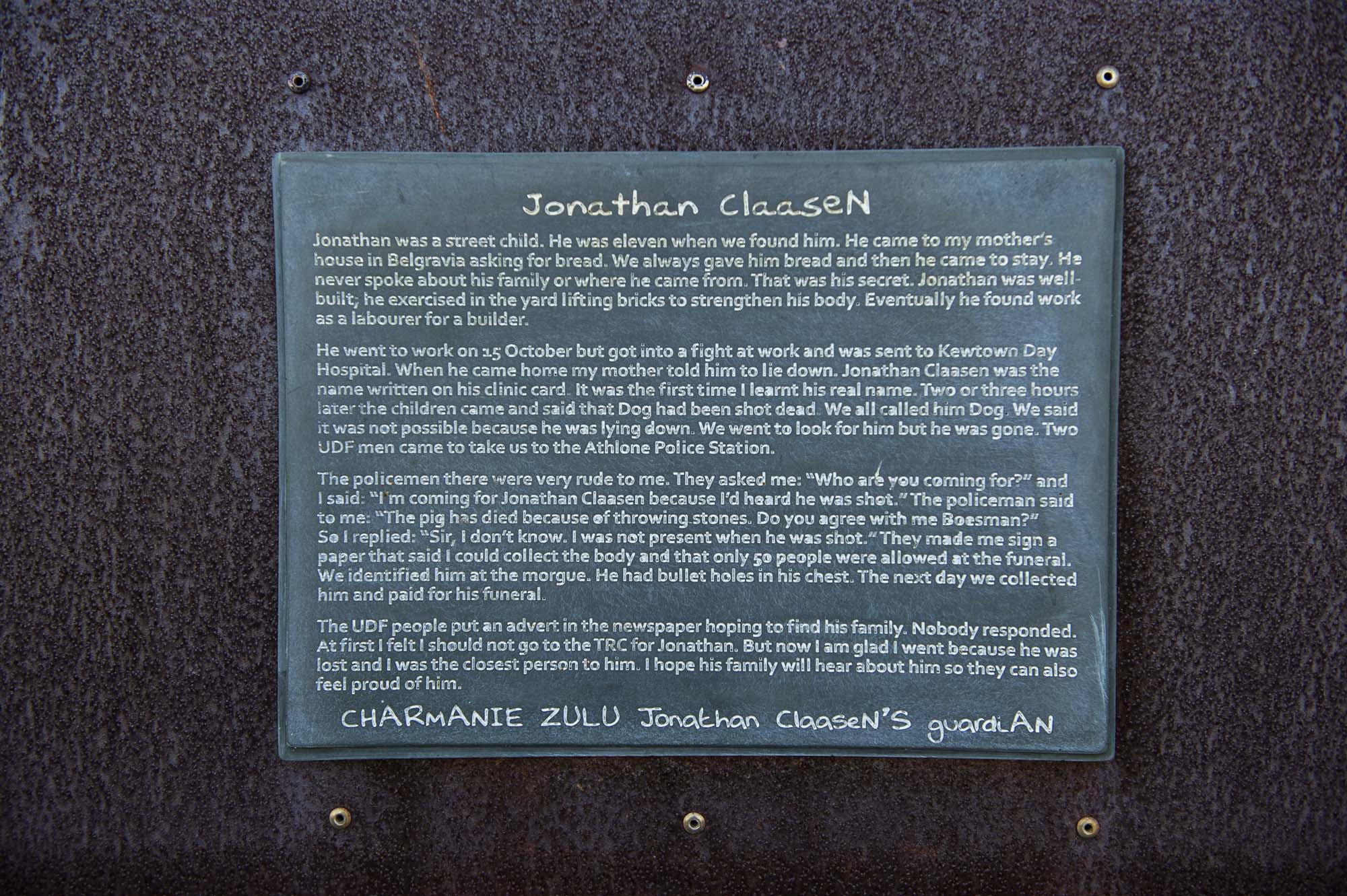

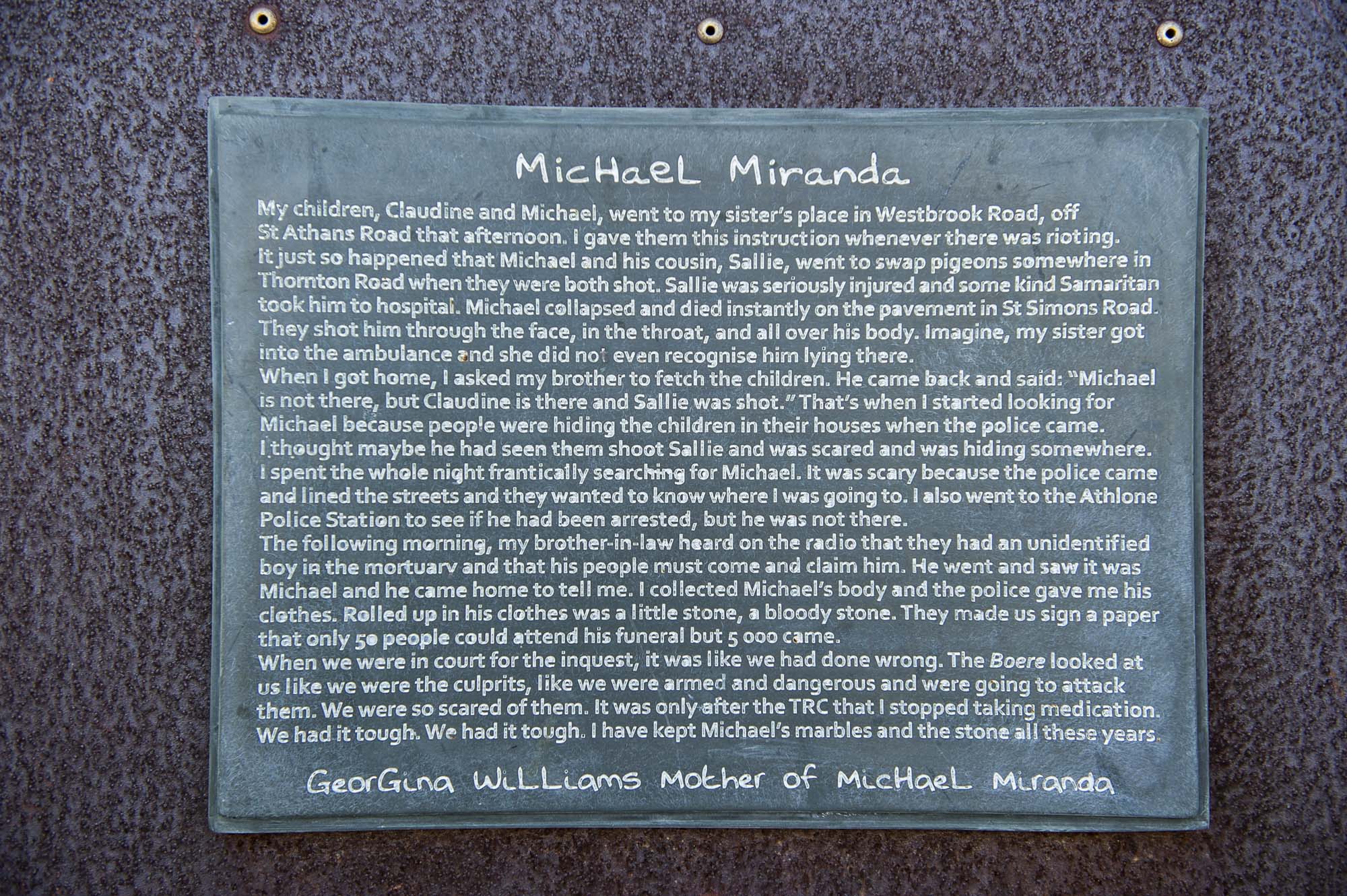

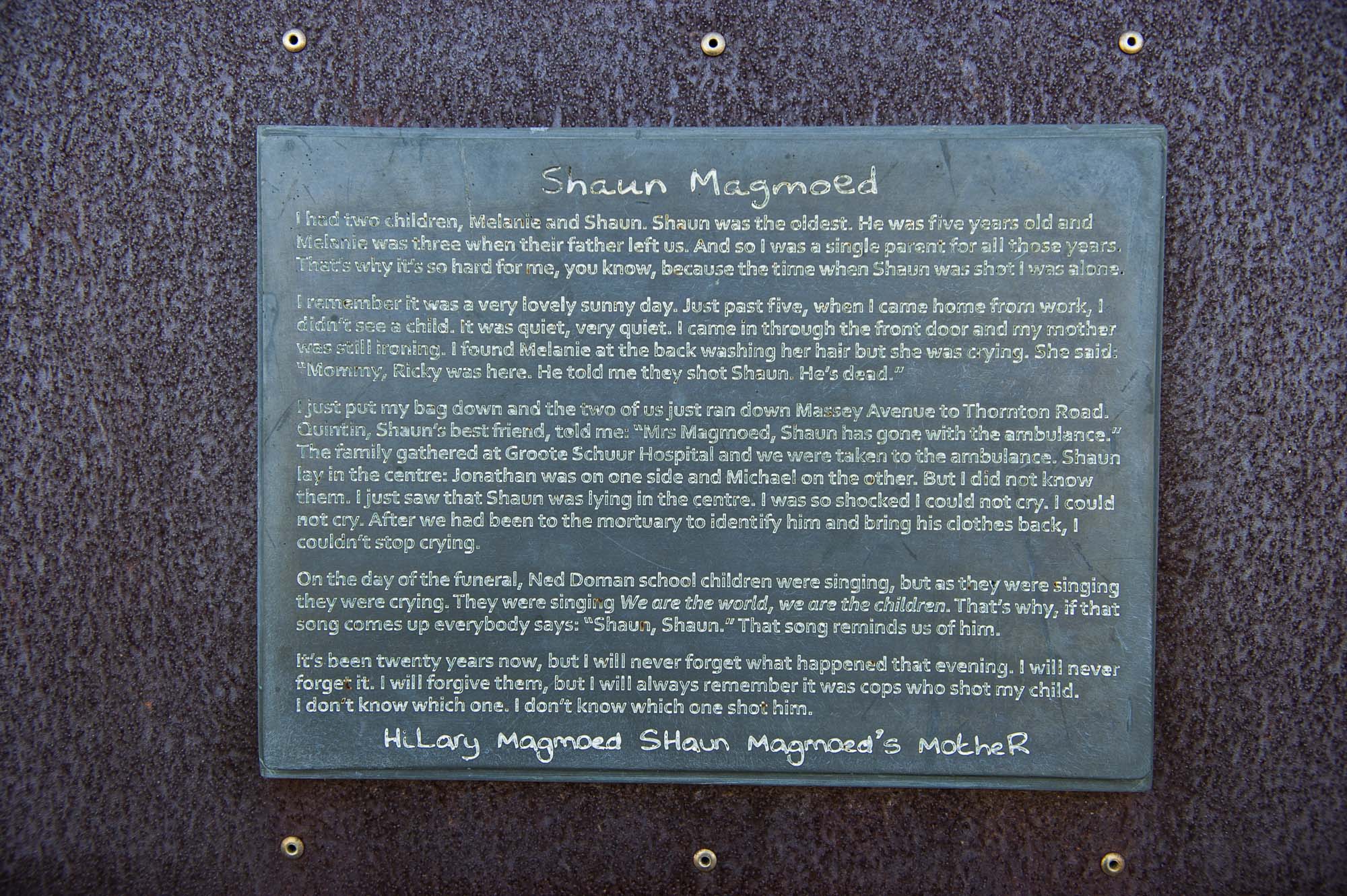

Three young people died that day, in what is now known as the Trojan Horse Massacre. Jonathan Claasen (21), Shaun Magmoed (15) and Michael Miranda (11) were murdered and several others were injured.

To this day, no one has been found guilty of their murder. This despite an inquest, an appeal and damning, unambiguous footage of the massacre, and named perpetrators and accomplices. “If you know who holds a firearm and discharges a bullet, you will know who killed those boys. Nobody was [found] culpable,” said Gunn.

A deliberate attack

At the time of the triple murder, Gunn was a Section 29 detainee. Upon her release, the MK veteran was updated by her comrades and neighbours in Belgravia, Cape Town. Many years later, after engaging with the victims’ families, she wrote a book titled If Trees Could Speak: The Trojan Horse Story and was instrumental in creating a memorial for the victims.

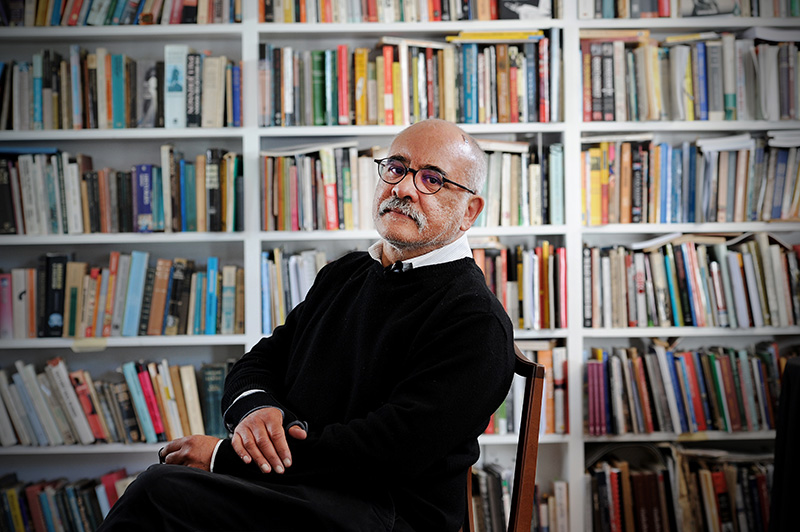

Another member of the UCT campus community who had a strong connection with the Athlone community is Emeritus Professor Crain Soudien. Now the chief executive of the Human Sciences Research Council, Soudien was, at the time, a teacher at Harold Cressy High School – a school known for its student-led resistance against apartheid.

In reflecting on that day, that which followed and what has unfolded since, it is clear that this was a deliberate attack, approved by the highest levels of the apartheid regime.

“This is the strategy of a government which was facing an uprising that, at that particular point, was ready to take arms. And so they were going to take people out; they were prepared to eliminate people,” said Emeritus Professor Soudien.

Dr June Bam-Hutchison, who is based in UCT’s Centre for African Studies and is the interim director of the recently launched Khoi and San Centre, was in hiding when the massacre occurred.

“It was a time of a State of Emergency in South Africa, of the brutal killing of children, hounding of teachers, the schools were closed … The country was up in arms,” she explained.

The Cape Flats erupted with news of the massacre: “It meant more mass meetings, more arrests, more anger, more violence … it was a very provocative, very brutal act.”

Across the country, the regime inflicted similar acts of violence and brutality against black South Africans. What had happened in Athlone was the apartheid norm, particularly at the height of the struggle in the 1980s. But what made that fateful day in Athlone different was that it was all caught on camera.

The Trojan horse

A team of correspondents from the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) – journalist Allen Pizzey, cameraman Chris Everson and soundman Nick Della Casa – were on the ground that day. Spotting the orange truck making its way down Thornton Road and, like the residents had, recognising it as a government vehicle, Everson began filming.

Unbeknown to the task force officers, the CBS crew had captured it all: the reconnaissance, the stone throwing, officers jumping from their crates and immediately opening fire with live ammunition.

They captured a young boy on his bicycle, frozen in terror as the perpetrators fired their shots. Their footage showed how the officers, after finally realising media had witnessed their crimes, chased the journalists away (but neglected to confiscate their equipment). And it showed the aftermath: wounded residents being rushed into ambulances and the bodies of the deceased being removed from the scene.

From Athlone, the CBS crew rushed the footage to the airport, and that very evening it was broadcast across the world. It became known as the Trojan Horse Massacre after Pizzey referred to the decoy truck as a Trojan horse. To the JOC, it was the “Ghost Truck”.

“Footage and images of violence are not always unambiguous. They can be used to serve various agendas,” said Dr Martha Evans from UCT’s Centre for Film and Media Studies.

Dr Evans, who was 11 at the time, explained that it was deemed a massacre not because of the scale but because of the “invidious method that the police employed to enter into the community”, which was caught on camera.

“That footage is totally unambiguous. It is unambiguously, indiscriminate firing into a crowd of mainly schoolchildren without serious provocation,” she said.

In addition to documenting history, the CBS footage had enormous international implications. That same night that the footage was broadcast, the Commonwealth was meeting in the Bahamas. One of the topics of debate was sanctions against apartheid South Africa, with United Kingdom Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher siding with the National Party.

“Thatcher lost the debate. [The footage] had huge implications, international implications, and therefore had a greater profile,” said Gunn.

The footage has also been crucial to investigations and hearings into the massacre. But it did not result in culpability. Nor did it stop the apartheid regime from killing again.

*The second article in this two-part series will be published on Friday, 16 October 2020.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.