UCT transforming, through the eyes of the Jaffer sisters

24 March 2021 | Story Carla Bernardo. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 10 min.

When the time came for award-winning journalist, author and activist Zubeida Jaffer to decide where she would pursue her undergraduate degree, the choice had to be the University of Cape Town (UCT) – but not for the reasons one might consider when making the choice today.

Rather, Zubeida chose to study at UCT because of the advice of her teachers, and in support of resistance against the University of the Western Cape (UWC) having been designated under the apartheid category (AC)* ‘coloured’. But applying to UCT came with its own challenges.

“We couldn’t participate in social activities because AC whites and AC blacks were not supposed to mix.”

First, she needed to apply for a major of which she had no knowledge: Comparative African Government and Law. It was a popular choice for black students who wanted to study at UCT because it was a degree that was not on offer at UWC – and a prerequisite for a second challenge. This second obstacle was receiving special permission from the Coloured Affairs Department, without which Zubeida could not study at UCT, regardless of the university’s decision.

Fortunately, she received the green light from both institutions, and began her studies in 1975.

Personae non gratae

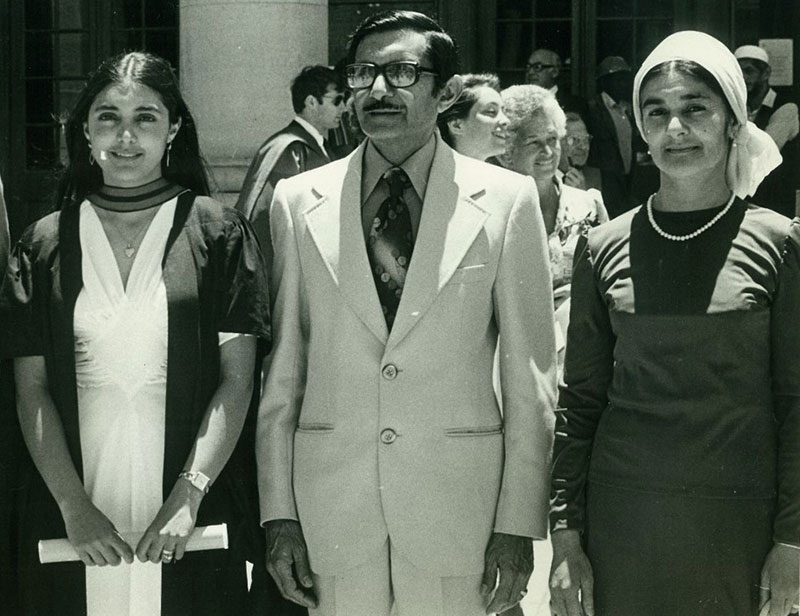

Speaking to Zubeida in her home in Wynberg, Cape Town, where her family has lived for over 60 years, she recalled how UCT was a “very strange place” for her and her older sister, Dr Zuleiga Jaffer. Zuleiga, who was a medical student at UCT, contributed to the interview via email.

Every day they would travel from the Wynberg train station to Rondebosch station, and then walk up the hill (there were no Jammie Shuttles at the time, Zubeida added). And then, at the end of the day, they would make their way back down and return home.

“We couldn’t participate in social activities because AC whites and AC blacks were not supposed to mix. So you couldn’t be going to the sporting events … you couldn’t participate as a normal student,” Zubeida said.

“And because we were there on a special permit, we felt we were being insulted, and that we were there personae non gratae. We weren’t there fully as students.”

The experience led many AC black students, including Zubeida, to boycott their graduation. While her parents were disappointed, because they were so proud of their daughter’s achievement, they understood the context (it was 1976), and that there was “no way” she could bow down in front of then-chancellor Harry Oppenheimer.

The year before, Zuleiga had opted to attend her graduation, but decided not to participate in the class photograph or attend the class dinner. While they had different approaches, both sisters chose to resist.

Anti-apartheid activism

During their time at UCT, both sisters were active in and supportive of the anti-apartheid movement, in addition to working in their community, and their acts of resistance during their respective graduation seasons.

In 1976, Zubeida and two friends – Tony Cochrane and Barry Saunders – decided to join the student-led protests in town. This ended in Tony being surrounded by police and beaten so severely that he was concussed. After losing their friend in the chaos, Zubeida and Barry found him and rushed him back to UCT, where they sought medical help. But even though they had become accustomed to “othering”, the response from the student health facility was shocking.

Staff on duty refused Tony medical care, despite him being in need of help, and a registered student.

“I didn’t expect that; I really didn’t,” said Zubeida.

In the same year, Zuleiga and Dr Sophia Kisting-Cairncross, a fellow intern at Somerset Hospital, organised workers to protest in solidarity with others around the country. Zuleiga and Sophia were also instrumental in calling a meeting with the heads of Medicine, Surgery and Gynaecology, following which brown-skinned registrars were allowed to work in Groote Schuur Hospital (though they were still barred from treating AC white patients).

Sustained, extraordinary contributions

Following their respective graduations, both sisters continued to contribute significantly to the liberation struggle and to their communities. Zuleiga came to be known as “the people’s doctor” in and around Grassy Park, where her family are well known for their contribution to the local economy and for their political activism.

Zuleiga served (and continues to serve) the community, often treating other activists who had been beaten by the apartheid police. She is an active member of community structures, and co-led the Lotus River / Grassy Park Residents Association. ‘Julie’, as she is fondly known, was an early campaigner for free healthcare for all, and contributed to the formation of the United Democratic Front alongside her sister.

When Zubeida left UCT, she joined the Argus Company (now Independent Media) to do a holiday job that, while not planned this way, was to be the start of a rich journalism career that spans more than 40 years. Through her work, as noted in the citation of her most recent award (the Allan Kirkland Soga Lifetime Achievement Award), Zubeida has “made a sustained and extraordinary contribution to journalism”, “demonstrated impeccable ethics and craft excellence”, and “enriched South Africa’s public life”.

She was arrested for her coverage of police killings in 1980, and again in 1986, when she was several months pregnant; and in the 1990s, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission declared Zubeida a torture survivor.

Return to UCT

Zuleiga has maintained a strong connection to UCT over the years as a parent, student, facilitator, lecturer, and – as she puts it – provocateur. In 1996 Zuleiga was appointed the deputy director of the Student Health Services (now Student Wellness Service). That year, Zuleiga’s son, Dr Riaad Moosa, enrolled to study at UCT and was able to see AC white patients, attend post-mortems of AC white people and work on AC white cadavers. In 2007 her daughter, Dr Yumna Moosa, followed in their footsteps and in a speech to the Class of 1975, Zuleiga told of how Yumna had a “full and balanced experience” at UCT, and was president of the Students’ Health and Welfare Centres Organisation: Education.

A year later, Zuleiga took up a teaching post in palliative medicine. She also served on a faculty committee known as White Privilege / Black Pain, alongside Professor Leslie London and Associate Professor Sipho Dlamini, and started a project called Healing through Transformation – Putting your finger on it, which was born of students’ experiences of racism in the field.

For Zubeida, a return to UCT took longer. But even by the late 1990s, when visiting the campus again after so long, she was struck by how many AC black students there were, particularly in comparison to the small group she was a part of in the 1970s.

And during a trip to the library, Zubeida was in for another pleasant surprise.

“I just couldn’t believe that there were AC black students, all these students, in the library; and I just stared. I stared – literally stared – because for us, it would have been all AC white students and a dot; one or two people, dotted around,” she said.

Later, she shared the experience with Zuleiga, saying that she understands why students continue to push for transformation. At the same time, “It’s chalk and cheese compared to where we were.”

While she hadn’t felt she could identify with UCT before, a “meaningful connection” was made as former vice-chancellor Professor Njabulo Ndebele stepped into his position at the university. Zubeida also went on to write her first two books, Our Generation and Love in the Time of Treason, in UCT’s Centre for African Studies and the African Gender Institute.

Now, she’s focusing on the launch of her own publishing company, No 10 Publishers, “to build my own independent voice, free from the vestiges and restrictions of past oppressors”. And while she gears up for the virtual launch on 24 March (RSVP: media@jtcomms.co.za), she’s also preparing for the launch of a co-edited book, Decolonising Journalism in South Africa: Critical perspectives, and the expansion of her personal website and The Journalist, a site she founded six years ago.

The sisters’ ongoing work demonstrated their continued support of transformation at UCT, in higher education more generally, and across society.

Referring to the importance of decolonisation, for instance, Zubeida remarked: “British students don’t go to university [to be] taught about the greats of South Africa … they’re taught about the person down the road. Their parents would be outraged if they were being taught about a journalist, for example, who is from another country, and told that this should be their inspiration.

“We are being told that all the time; it’s standard fare,” she said.

Finally, Zuleiga added that while much has changed at UCT, much still needs to be done. She paid tribute to those from her and Zubeida’s generation, those who came before and concluded with a call to action.

“We would like to call on all the people at UCT to make their contributions in small ways and big, to work towards an institution where no one feels less than; where it is a home for all.”

“Then, indeed, UCT can be recognised as our true alma mater; our bountiful mother,” she said.

*As per the request of the interviewees, ‘apartheid category’ (AC) is used when referring to black, white, coloured and Indian to denote that these are categories assigned to people by the apartheid government. Both sisters reject any racial labels attached to them – then and now – and see themselves as South Africans and children of God.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.