Trojan Horse Massacres: ‘It’s like it never happened’

16 October 2020 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Journalists Aamirah Sonday and Carla Bernardo. Camerawork Mad Little Badger. Video Edit Mad Little Badger. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 10 min.

This is the second of two articles by UCT News, which commemorate the 35th anniversary of the Trojan Horse Massacres.

In the immediate aftermath of the massacre in Athlone on 15 October 1985, the perpetrators returned to their base at the nearby Manenberg police station where they regrouped to continue planning what is now known to have been a two-pronged attack.

The joint task force, organised by the National Joint Operational Centre (JOC), had initially intended to take the “Ghost Truck” through Athlone and nearby Crossroads before returning to their base in Manenberg. However, in the aftermath of the shooting they were forced to abort the second half of their mission – but only for a day.

Massacres, plural

The next day, the JOC sent another truck, again disguising it but this time painting it blue, into Crossroads. And to ensure the apartheid officers had better visibility, they cut peepholes into the crates, again stacked around the back of the truck and again hiding them and their weapons.

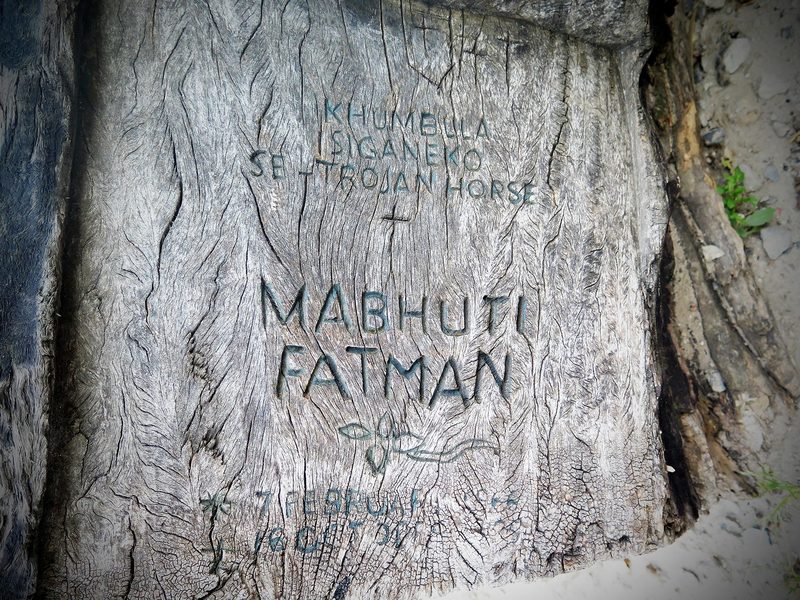

Two young men, Mabhuti Fatman (20) and Mengxwane Mali (19), were enjoying a game of soccer when they spotted the blue truck crawling down the dusty, lower end of Klipfontein Road. They decided to play a game, not knowing what was hidden by the crates.

“They jumped on the back of the truck to hang on the tailgate, the game that you played, I played, many of us played,” said University of Cape Town (UCT) alumnus, anti-apartheid activist and uMkhonto we Sizwe (MK) veteran Shirley Gunn.

At that moment, the JOC officers jumped up and began shooting. In Crossroads, there were no stones thrown. But just as had happened in Athlone 24 hours earlier, the task force members didn’t fire warning shots, they didn’t use tear gas – they fired indiscriminately. Fatman and Mali tried to run away but the apartheid police gunned them down and both died alongside the road.

Bullets sprayed, hitting babies in nearby shacks, and again, like in Athlone, many unsuspecting residents were injured. In total, five youths were murdered by the apartheid police in the space of 48 hours, and five families and their communities were devastated. The Trojan Horse Massacre is, in fact, the Trojan Horse Massacres.

A historiographic problem

Despite international outrage and condemnation, despite increased resistance in response to the massacres and the rare capturing of these apartheid atrocities on camera, the Trojan Horse Massacres and the contribution of the Western Cape to the liberation struggle is not well documented.

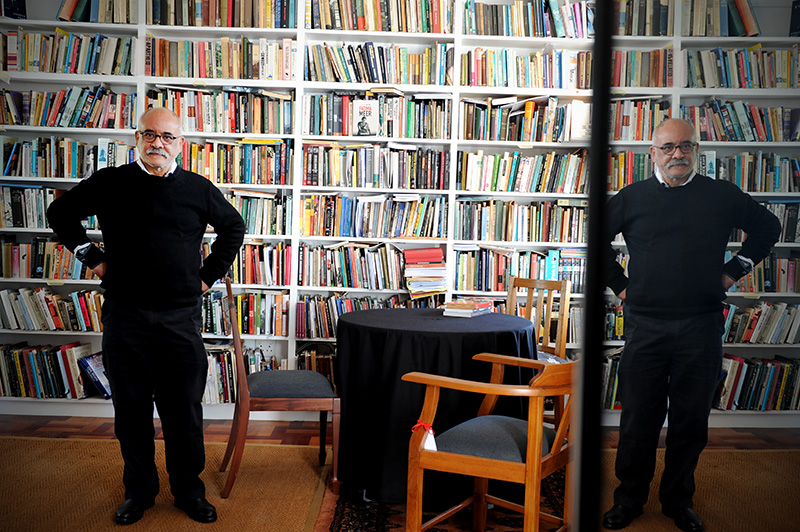

“A lot of that has to do with … traditions of telling the story of what the resistance movement is all about in the country,” said Emeritus Professor Crain Soudien.

Now the chief executive of the Human Sciences Research Council, Soudien was, at the time, a teacher at Harold Cressy High School – a school known for its student-led resistance against apartheid.

“So youʼre looking at what I would call a historiographic problem. Itʼs a problem about who is in the story and what the story represents in terms of the liberation movement.”

Events closely aligned with the African National Congress (ANC) tend to be much more prominent than those not explicitly linked to the party. What happened in Athlone could not easily be linked to the ANC: It was ordinary people responding to and resisting the apartheid regime. Athlone’s ties to the anti-apartheid and non-racial mass coalition, the United Democratic Front (UDF), were, however, strong.

Student movements were also prominent in Athlone and across the Cape Flats and housed within UDF’s Congress of South African Students. However, Soudien noted, despite less explicit links, the students would have been inspired by and aware of the activities of the ANC. But, he added, this was not a moment for which an organisation could take credit.

For Soudien and many of his peers, those particularly active in the 1980s when the leadership of the ANC was either in exile or detained, it is as if this part of the liberation struggle has been erased.

“Youʼll hear a whole lot of us who come out of that particular period who are extremely disappointed with what [happened] after 1990 because that whole contribution of the 1980s is almost switched off – itʼs like it never happened,” he said.

This contribution, he added, continues from and is related to the 1976 Soweto Uprising and strengthened the liberation movement through the solidarity of ordinary people, workers, trade unions and students.

“The contribution of the Western Cape, here, was in laying down a model for how communities could be organised,” he said.

Finding closure

Echoing Soudien, Dr June Bam-Hutchison, who is based in UCT’s Centre for African Studies and is the interim director of the recently launched Khoi and San Centre, said that there has indeed been erasure but also forgetting.

Factoring into this is the negotiated settlement that benefited capitalist elites and not the majority; the unfulfilled promise and purpose of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC); and the push for a “rainbow nation” where the oppressed were expected to forgive.

“There is an erasure about how inclusive the struggle against apartheid was – beyond race. There are many misunderstandings of sites of struggle, who was in the struggle, who paid the ultimate price, and who didnʼt,” said Dr Bam-Hutchison.

The African Studies scholar and anti-apartheid activist added that “there has been no closure because itʼs never been fully acknowledged as part of this countryʼs history”.

“Itʼs never been fully dealt with at the TRC and the perpetrators walk freely in the new South Africa.”

“Itʼs never been fully dealt with at the TRC and the perpetrators walk freely in the new South Africa.”

Bam-Hutchison provided some recommendations for starting the process of building an inclusive narrative of the struggle, of addressing the injustices and of helping victims’ families and communities heal and be acknowledged for their contribution.

First, the consciousness and teaching about the inclusivity of that struggle must be brought back in ways such as giving meaning to how the massacres are remembered in history curricula. Second, the massacres, as well as other stories where there has been similar erasure, must be positioned in the broader and ongoing struggle against material injustice.

“By forgetting them, these children, what happened, how the youth was organised in fighting injustices … weʼve also done an injustice to the economics,” said Bam-Hutchison.

“They are part of a bigger story of poverty and deprivation because apartheid wasnʼt just about race discrimination – it was also about structural impoverishment, according to colour. By forgetting them, we forget what the struggle was about.”

The third recommendation is to acknowledge and better document the long trajectory of struggle in the Western Cape, which can be traced back to the 1600s when the Khoi fought numerous battles against the Dutch colonisers. And it can be connected most recently with the Fallist movement, which had similar concerns about the quality of and universal education, food security and workers’ rights.

And finally, Bam-Hutchison recommends that to help the victims of apartheid atrocities – such as the five families – find closure, the TRC’s work, after taking into account the many criticisms justifiably levelled against it, must be revisited and extended to address the atrocities and to bring perpetrators to justice.

“May those families find closure, may South Africa take seriously the issue of continued memory and the inclusivity of the struggle against apartheid because that is important to recognise, to be able to have a more inclusive dispensation around the variety of issues of material injustice.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.