The boy who would build a nation

11 July 2019 | Story Carla Bernardo. Read time >10 min.When liberation struggle icon Denis Goldberg was a little boy, he dreamt of becoming an engineer. He wanted to build one of the “great engineering works”: South Africa’s own Suez Canal, with interstate water pipelines and a Brooklyn Bridge. He wanted to build it for his country and its people. And while it wasn’t quite the building Goldberg had imagined, a builder he would indeed become.

At home in Hout Bay, surrounded by his impressive collection of local art, the 86-year-old recounted the incredible details of his life journey ahead of receiving his honorary doctorate from the University of Cape Town (UCT) tomorrow, 12 July.

“I was a clever little boy, I have to tell you,” he said.

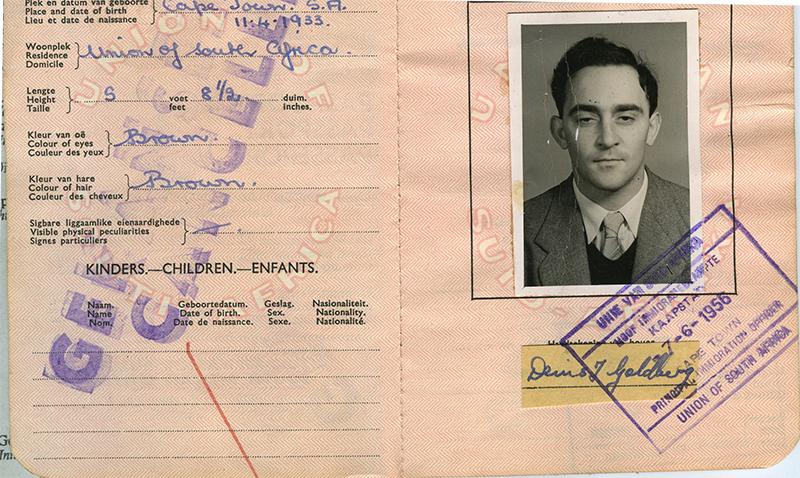

Born in 1933, six years before the start of World War II, Goldberg began learning about that war through newspaper headlines he read while seated on his father Sam’s lap. While he couldn’t explain what was going on “up north”, the young boy knew terrible things were happening. It was one of the earliest lessons in his lifelong political education.

In 1939, just months before Germany invaded Poland and sparked the global conflict, Goldberg began his primary education at the all-white Observatory Boysʼ School. It was a lonely place for him: He had a Jewish surname and encountered anti-Semitism from both peers and teachers. His parents Sam and Annie were immigrants and communists, and, already, Goldberg was aware of the many injustices that surrounded him.

But school was also where he encountered one of his inspirations, his first teacher, Miss Cook.

He recalls an incident when Miss Cook’s watch disappeared from her desk drawer. When probed, the class – including Goldberg – blamed a boy named Nolan who had a harelip and cleft palate. Miss Cook called on Goldberg, asking him why he thought it was Nolan. With no evidence of Nolan’s alleged crime, Miss Cook took time to teach the class about prejudice: They were blaming him because he looked and sounded different.

“Miss Cook [was] somebody who understood how easy it is to blame the outsider, the different person. And in a way, I suppose, she is part of the influences that took me to prison,” he said proudly.

Goldberg’s solid political foundation strengthened when, after matriculating, he spent time on a family friend’s fruit farm in Ceres. There, he saw the reality of the hardships the farmworkers experienced.

One of his memories was seeing the farmworkers’ children walking barefoot on the hot tar roads. The skin on their feet had become so thick that they slept unaware that rats and mice were gnawing at them. They’d just awaken to see the evidence.

“Work on the farm really was an eye-opener because it’s not just a book; you actually see it happen,” he said.

A lonely place

Still yearning to build for his country, Goldberg enrolled to study civil engineering at UCT. At just 16 years old, he started his BSc as possibly the youngest in the class and the first in his family to attend university.

But much like school, university was a lonely place for him. Filled with hopes of a vibrant space featuring rigorous debate, he was disappointed to find that right-wing ideology was alive on campus. In his engineering classes, despite his efforts to persuade them otherwise, his classmates made it clear they supported the apartheid regime.

And because of his age, Goldberg couldn’t join in the social life of the university and a busy class schedule prevented him from “hanging out” on campus.

“Engineering students don’t hang out on campus … [We were] terribly jealous of the arts students who could go and drink coffee and chatter away.”

Fortunately, he could “kick the hell out of a ball” and joined UCT’s under-19 rugby team. With rugby’s status on campus, being part of the team afforded Goldberg some social capital in and outside of the classroom.

“I’ve had tremendous comradeship, I must say.”

But the budding political activist had also joined the Modern Youth Society (MYS), an off-campus outgrowth of the UCT student body, Modern World Society. MYS was open to youth across colour and class lines. Pressed for time, Goldberg had to choose between politics and rugby – and the former won.

MYS provided him with a space to share and hone his political values and goals. It also introduced him to one of the most important people on his life journey: Esme Bodenstein. They fell in love, married in 1954 and had two children, Hilary and David. Bodenstein was a political activist in her own right, and Goldberg describes the attraction as more than just physical; it was, it seems, a meeting of political minds.

And so, the loneliness Goldberg had faced throughout school and university began to dissipate.

Building bonds

As he became more active, he began to form bonds that would last a lifetime.

In 1957, he joined the banned Communist Party and by 1961, he was a member of Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), the armed wing of the African National Congress (ANC). These organisations, among numerous others, provided fertile ground for comradeship: Goldberg would go on to meet fellow struggle icons like Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, Bram Fischer, Ahmed Kathrada, Albie Sachs and Chris Hani.

Of each, he has many fond memories.

One was how Mandela, who attended a private missionary school, called Goldberg “Boy” because he was 15 years younger than the MK founder. It was a major inversion in South Africa, the memory of which still makes Goldberg laugh. He, in turn, referred to Mandela as “Nel”, his term of endearment for the first democratic president.

He also remembers fondly the conversations and lessons he’d receive from Sisulu during their time underground. Most importantly, Goldberg learnt from the “arch-exponent” himself, ways in which to draw people into your movement and towards your ideas.

“I’ve had tremendous comradeship, I must say,” the liberation icon said.

Throughout his recollections, he refers to comrades and comradeship. But, he explained, the word now lacks meaning.

“The word … is used very lightly. Anybody who is in the movement is a comrade,” he said.

“So friend becomes much more powerful.”

“In the Rivonia Trial … you faced the gallows together. It is a bond you can’t break.”

For Goldberg, “comrade” has lost its “specificity of people who are prepared to risk their lives together as we were”.

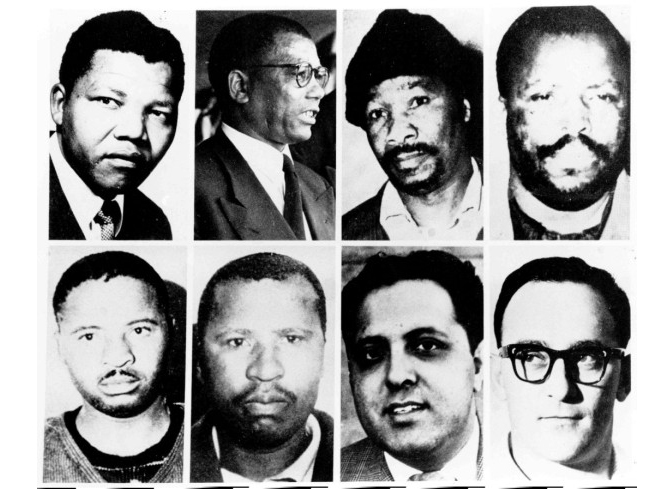

In 1963, an unbreakable bond was formed between the comrades known as the Rivonia trialists. At the end of the trial, Mandela, Sisulu, Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, Elias Motsoaledi, Andrew Mlangeni, Raymond Mahlaba and Goldberg were found guilty of sabotage, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

“In the Rivonia Trial … you faced the gallows together. It is a bond you can’t break,” Goldberg said.

And while only two of the trialists are still alive – Goldberg and Mlangeni – that special bond remains intact.

Release, tragedy and joy

In 1964, Goldberg was sent to serve his sentence at the whites-only Pretoria Central Prison. The rest of the trialists were sent to Robben Island. Goldberg was isolated from his comrades and alone in a prison where anti-apartheid activists were pariahs.

But he kept busy, furthering his studies so that he would be ready when the time came to help better the country. During his 22-year imprisonment, Goldberg managed to obtain a degree in public administration, a BA and a degree in library science. A few years into his sentence, he was no longer alone as comrades including Fischer and Jeremy Cronin were also detained at the prison.

In 1985, Goldberg became the first trialist to leave prison. He immediately went into exile, joining Bodenstein and their children in London. He continued the work of the ANC there, leading public campaigns calling for the release of his fellow trialists. By 1990, all had been released.

“You can corrupt a government in a few years but to overcome it… it’s going to take a very, very long time. Maybe generations.”

Between 1994 and 2002, he served as founding director of the development organisation Community HEART (Health, Education and Reconstruction Training) in London, and is now its honorary president.

The early 2000s represented both tragedy and joy for Goldberg. In 2000, Bodenstein died from cancer and two years later, their daughter Hilary died suddenly from a blood clot.

In 2002, Goldberg married his second wife, Edelgard Nkobi, returned to South Africa and accepted a position as special advisor to the Minister of Water Affairs and Forestry.

Renewed optimism

Fast forward a few years after his return to South Africa, Goldberg continued his political activism, using his platform to call to order those he deemed had transgressed the core values of his beloved ANC. During the Zuma years, Goldberg was a staunch critic of state capture and of the degrading of the ruling party.

Fortunately, the election and appointment of President Cyril Ramaphosa have renewed Goldberg’s optimism.

“I trust him implicitly,” he said.

Goldberg has spent time talking to Ramaphosa, and explains that the task the president has been given is an almost impossible one.

“We want him to restore democracy in the ANC and in the country, to lead the way, and at the same time, we want him to deal in an authoritarian way with those who are opposed to democracy.”

But Ramaphosa has assured him that he need not worry, and that it’s all about timing in politics. Goldberg said this shows in how the president deals with problematic figures in the movement: He waits for the transgression, giving him grounds on which to discipline the member.

The struggle veteran is hopeful the country’s courts will catch up with those who have committed crimes within government and the ANC, but calls for the public’s patience.

“You can corrupt a government in a few years but to overcome it… it’s going to take a very, very long time. Maybe generations.”

House of Hope

While Ramaphosa’s election has renewed Goldberg’s hope, South Africa’s young people have kept the seasoned activist’s dreams of nation-building alive.

Despite the Zuma years, ongoing poverty and inequality, young people continue to put up their hands and offer their help in rebuilding the country.

“I am optimistic because young people want to get on with the job.”

“I am optimistic because young people want to get on with the job,” said Goldberg.

In 2016, he founded the Denis Goldberg Legacy Foundation Trust. A major part of their work has been the creation of the House of Hope (HOH), a space in Hout Bay where young people from across the peninsula can bridge the many divides, engage in cultural activities and skills building, and learn about one another.

“We don’t talk social cohesion, we do social cohesion,” he said proudly.

While the HOH’s work has already started, they have yet to build the actual house. So far, the land has been secured through a 99-year lease, plans have been drawn up and they are now awaiting approval from the City of Cape Town. The HOH has raised R3 million already, with a promise of another R3 million to come.

UCT’s Chair of Council Sipho Pityana, who is also independent non-executive chairman of AngloGold Ashanti, has promised HOH a donation from the mining company of R1.5 million over a few years. Major donations have also come from the Mauerberger Foundation Fund. Much of the work on the building plans was given as a gift to the HOH and Hout Bay, particularly to Imizamo Yethu and Hangberg.

“My project, I hope, will encourage people to say there’s hope, the House of Hope,” said Goldberg.

The foundation is also trying to crowdfund and is hosting screenings of Goldberg’s film, Life is Wonderful: Mandela's Unsung Heroes. UCT will host a screening on Mandela Day at a cost of R50 per ticket.

The nation builder

Goldberg’s life has come full circle. As a young boy, filled with the hope of one day helping to build for his country, the liberation hero is giving young people hope and opportunities to construct the country they deserve.

In recognition of his courage and enormous contribution to the liberation struggle, UCT will confer an honorary doctorate on the alumnus.

Tomorrow he will be honoured in front of PhD and Graduate School of Business graduands as well as close friends, including Pallo Jordan, Blanche La Guma and Andre Odendaal. And he couldn’t be prouder.

“I am very proud … that my university, my alma mater, my sweet mother … is, at last, recognising the fact that a guy who made weapons to put an end to the state violence, needs recognition.”

This recognition, he said, shows that engineers, despite the department’s and field’s conservative history, can be progressive.

And while that young Goldberg had once dreamt of creating great engineering works and sitting atop one of “those great big yellow machines”, he is satisfied that through the liberation struggle, he has helped build the road on which others can do so.

“We’ve done it so somebody else is riding those machines. Big Bill the construction boss, that’s what I wanted to be. And here, we’re doing it.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.