‘Grachte’, pumps and the first hydroelectric station – how water shaped the city

03 February 2023 | Story Helen Swingler. Photos Supplied. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 10 min.

Day Zero in 2018, triggered by a severe drought in the Mother City and with taps predicted to run dry on over four million people, marked a crisis like none before. But the region has always been water thirsty. This saw early Dutch and British settlers take matters into their own hands to provision ships on the East Indies route and, later, the fledgling centre’s growing settler and slave population.

Each development since the 17th century has made its mark on various natural landmarks and on the city’s geography and infrastructure, said the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Emeritus Professor Jenny Day in her UCT Summer School lecture, “Water for Cape Town: 370 years of ‘not quite enough’”.

Emeritus Professor Day’s lecture was also livestreamed to the Denis Goldberg House of Hope (DGHoH) in Hout Bay. This is one of three community satellites that have opened Summer School’s offerings and reach to new audiences, with similar satellites at the SHAWCO Centre in Kensington and the Philippi Hub, introduced last year.

Shaped by water

Cape Town’s history of water is tightly connected to how many people have needed it through the centuries, said Day. In 1658, a few years after Jan van Riebeeck arrived at the Cape to establish a victualling centre, the population was “a comfortable” 360 people.

The journey from Europe to the lucrative East Indies was tediously long. A halfway house was needed. Long before Van Riebeeck landed in the Cape, mariners from Portugal and Spain were trading with the local Khoi people in return for water, livestock and vegetables.

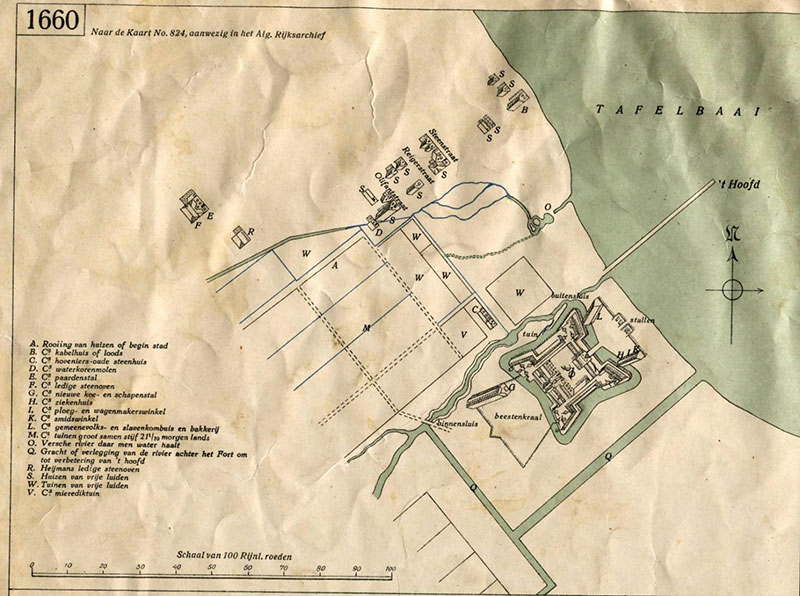

But as fleets grew, there wasn’t enough water to supply all the ships calling at the Cape. As a solution, the Dutch built a small settlement (later Cape Town) and one of their first tasks was to build grachte, or canals, to harness the precious resource, said Day.

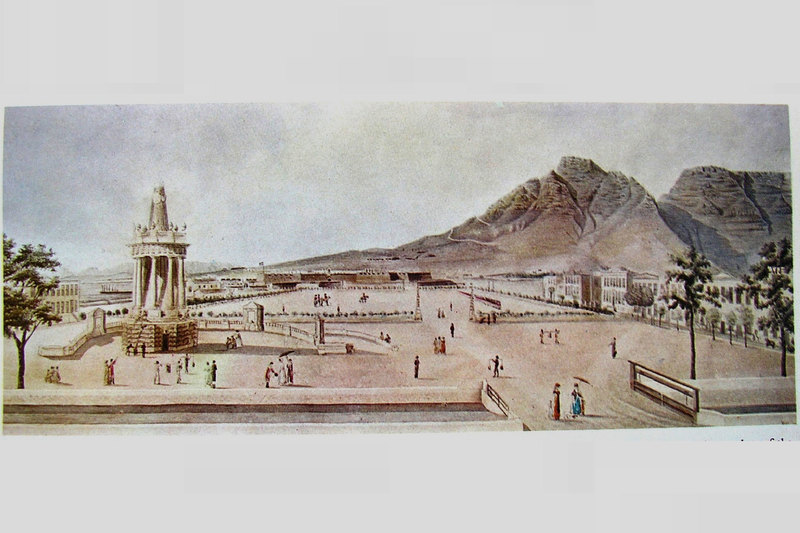

A map in the archives of the Cape Orphan Chamber shows an early Dutch four-pointed wooden fort, surrounded by a moat. This was later replaced by the five-pointed stone fort, known as The Castle, also with a defensive gracht.

Of the two streams coming off Table Mountain, one was partly canalised to bring water to The Castle, in the area now known as the Company’s Gardens where the fruit and vegetables were grown. And this ended in a watering spot where the ships could collect water.

“The Dutch have always had a love/hate relationship with water,” said Day. “They love to have it around but in the right places – and not too much of it. Dykes and canals were used to control the flow. They thought this was the right thing to do in Cape Town – not realising that in summer there’s very little water around.”

It also became imperative to secure more water once the population began to grow.

Reservoirs of water and wood

When Zacharias Wagenaer replaced Van Riebeeck as the Dutch governor in 1663, he built a rectangular masonry reservoir, about one-third the size of an Olympic swimming pool, between The Castle and the bay. Because the available labour force was so small, he ordered every able-bodied person to work on the construction.

Remnants of Wagenaer’s reservoir were unearthed (and later conserved) during excavations for the construction of the Golden Acre in Adderley Steet in 1975.

To move water from the reservoir, and in the absence of metal, the Dutch took to the Table Mountain forest, bored holes through tree trunks they’d felled and created a pipeline. But these were slow-growing, and once they’d been used for making pipes and as fuel for the ships’ galleys, the forest simply disappeared. The Dutch then turned to what became known as Hout (wood) Bay around the corner, said Day.

As the fledgling centre grew to include a hospital, a church and slave quarters, the Dutch grachte still moved water around the settlement. But there was no sanitation and chamber pots and other waste were simply emptied into the grachte.

“It was pretty nasty,” said Day. “Reports and letters right up until the end of the 19th century commented on the fact that the town was really unpleasant to be near.”

In the 1800s they needed to start damming water in a much larger way. When the British took over the Cape in 1806, the three main grachte were Buitengracht, Keizersgracht and Heerengracht. But to provide water to the inner parts of the city there was a leiwater (irrigation canal) scheme with sluices to prevent flooding. But these canals were also quite fetid and the British eventually covered them.

Between 1800 and 1850 the population spiked and a water shortage ensued again. The British borrowed a large sum to build a water house in Hof Street in 1819, which held some 11 000 m3 of water and cost £1 997/14/-, raised by introducing a “pipe tax”. It was demolished in the early 1900s.

Over time, households no longer had direct access to mountain streams. Instead, water was captured in dams in the city bowl and diverted along wooden waterways and iron pipes into wells as part of an improved water scheme for the city designed by Sir John Cradock in 1812.

Above each well was a pump house with a swaai (swinging pump). These were known as Hurling pumps after the Swedish inventor Jan Frederick Hurling. Slaves would swing the weighted handle from side to side, producing water from a pipe, often from the mouth of a bronze lion, like the Hurling Pump that still survives in Prince Street. These hand pumps were scattered about town where the citizens (usually their slaves) could pump water for household use.

Never enough

But there never was quite enough water, said Day.

By 1836, with a population that had swelled to 20 000, the authorities turned to the Platteklip Stream coming off Platteklip Gorge for water supply.

A few other springs were also used as a resource in case of fire (the city was devastated by fire in 1798) and for cleaning butchers’ “shambles”, or open-air meat markets. These springs also fed irrigation needs and powered the flour mill in Hope Street.

A series of municipal wash houses for public use were also established along Platteklip Stream. Sand-bed filters were introduced to control pollution.

But in 1849 Platteklip Stream was flowing at only two gallons a minute, the equivalent of a 10-litre bucket. A new reservoir became essential, said Day, and this was built in 1856 between Orange and Hof streets, to dam the water from the Oranjezicht spring. It’s still there today.

Six years later, a new reservoir was added, built at a cost of £2 710/3/1. By 1865 the city’s population had grown to 28 400. In 1866 the city bought Platteklip Stream from the Van Bredas as it flowed through their land and belonged to the family, as Roman Dutch Law decreed.

By 1875, just 10 years later, the town had grown to 45 000 people. The reason for the rapid escalation? Diamonds.

“And the best way to reach the diamond fields of Kimberley was via the Cape,” Day noted.

Reservoirs and a power plant

By 1877 the city’s daily water consumption had risen to 2 200 m3. The Cape Town City Council borrowed £50 000 from the United Kingdom to build a new reservoir, the Molteno Dam, completed in 1881. In 1895 a hydroelectric and steam power plant was built at the site and named Graaf’s Electric Lighting Works after David de Villiers-Graaf, mayor of Cape Town from 1891 to 1892, who personally funded its construction.

It wasn’t the country’s first electric power plant. That distinction went to Kimberley, which had a plant to supply electricity for street lighting. Cape Town’s power plant building still stands at the west of the Molteno Dam and is a national monument.

In addition, the city decided in 1870 to augment water supplies by building a reservoir on Table Mountain. The job went to a Scots hydraulic engineer, Thomas Stewart. The Woodhead Tunnel was built between 1888 and 1891 to divert water from the Disa Stream supplying Hout Bay to the reservoir.

Curiously, a small settlement was established at the mountain-top building site, with its own shop and post office – such was the effort it took to transport builders up and down the mountain.

This dam was completed in 1897. Four others followed: the Hely-Hutchison Dam, built in 1904; the Alexandra and Victoria dams in 1903; and the De Villiers Dam in 1907.

Though much larger dams were later built, such as the Wemmershoek and Theewaterskloof dams, now belonging to government, the city must still guard its precious water supply, said Day.

“We will continue to have floods and droughts, which will become more and more severe as climate change continues to get worse,” she added. “And the story of how Cape Town is dealing with the problem of not enough water will be a very interesting one.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.