Encoding the values of transformation

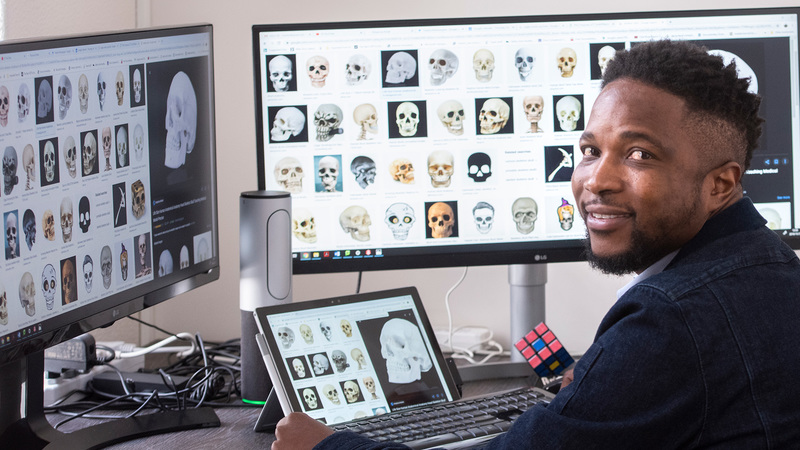

04 November 2019 | Story Nadia Krige. Photo Brenton Geach. Read time 6 min.According to Dr Tinashe Mutsvangwa, an expert in medical imaging in the University of Cape Townʼs (UCT) Division of Biomedical Engineering, he played only a minor role in what has come to be known as the Sutherland Project – an internationally precedent-setting process of restitution and reburial initiated by UCT in 2018.

Without his expertise, however, the individuals whose skeletal remains were unethically exhumed and donated to the university may forever have remained faceless.

The restitution process was set in motion when Dr Victoria Gibbon, senior lecturer in biological anthropology and curator of UCT’s skeletal collection, performed an archiving audit of the collection in 2017 and identified 11 human skeletons that had been obtained unethically in the past.

It was established that nine of the skeletons had been donated to UCT by a medical student between 1925 and 1931. Eight had been exhumed at Kruisrivier, the studentʼs family farm just outside Sutherland in the Northern Cape, and are believed to be the remains of San and Khoe farm labourers.

It was decided that the university had a responsibility to return the skeletons to their place of origin where they could be laid to rest near their families.

Gibbon visited the Sutherland community to receive input from the Abraham and Stuurman families – who had been identified as descendants of at least two of the individuals in question – on the next steps.

Rather than opting for immediate reburial, as Gibbon had expected, the families agreed to further research being conducted into the lives and deaths of their ancestors. They also made a specific request for facial reconstructions to be done, in order to have a visual representation of who their predecessors were.

“A particularly memorable moment of the project for me was being able to show the families a virtual model of one of the individuals.”

An unusual opportunity

As group lead for Medical Image-based Inferencing and Distributed Diagnosis (Mi2d2) – a research group in the Division of Biomedical Engineering at UCT – Mutsvangwa has established himself as an expert in the development of advanced medical imaging and analysis. It comes as no surprise then that Gibbon would ask him for assistance.

Seizing the opportunity to be part of this remarkable initiative, and using funding provided by the Medical Imaging Research Unit within the Division of Biomedical Engineering, Mutsvangwa and his PhD student Yvonne Karanja undertook the computed tomography (CT) imaging of the remains of the nine Sutherland individuals at UCT Private Academic Hospital in Cape Town.

“The main challenge was working out the logistics of getting the remains to the hospital in a way that was both dignified and respectful,” Mutsvangwa said.

“We also had to make sure that they wouldn’t be seen by the general public or that any accidental revealing took place.”

This was achieved by encasing the remains in bubble wrap and concealing them in wooden boxes. Once at the hospital, Karanja carefully removed each skeleton and – with the utmost respect – positioned the remains in the CT scanner.

“We took high resolution images of the remains, after which I did the post-processing and analysing of the CT scans,” he explained.

This was done with software that is widely used for medical image analysis research. The process involved a careful delineating of the cranium in the CT scan – differentiating it from the background – in order to reconstruct an accurate 3D digital model of each skull.

The 3D models were then sent to Kathryn Smith, a South African visual artist currently completing her PhD in facial reconstruction in the United Kingdom, at Liverpool John Moores University’s Face Lab.

“We also had to make sure that they wouldn’t be seen by the general public or that any accidental revealing took place.”

Using these models, Smith produced accurate facial reconstructions of the individuals, which have been presented to the families.

“Working with Kathryn to facilitate the depiction of these individuals was a nice secondary outcome of this project for me,” Mutsvangwa said.

“I really enjoyed these collaboratory efforts and the spirit of camaraderie that came with them.”

Closure for families

During the first viewing of the remains at UCT by the Sutherland Abraham and Stuurman families, Mutsvangwa was on hand to discuss his work with them.

“A particularly memorable moment of the project for me was being able to show the families a virtual model of one of the individuals,” he recalled.

“I could see the amazement on their faces and how meaningful this was to them.”

Mutsvangwa added that he believes having visual depictions of the deceased – individuals who had previously been faceless and nameless to their descendants – certainly offered the families a sense of closure and maybe a final understanding of what had occurred in the past.

It was a profound experience for him, to be part of a process in which the university was actively reconsidering its position within society and trying to make some amends for harm done in the past.

“From the start, it appealed to my deep sense of social justice,” he said.

“It really kind of encodes all my values in one project.”

While the notion of transformation may be familiar to most South Africans, he added, it’s rare to see it employed in such a tangible manner.

“The university has set a precedent with this process, which I believe could serve as a good blueprint for other institutions.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.