Digital technologies a cultural lifeline for Somali diaspora

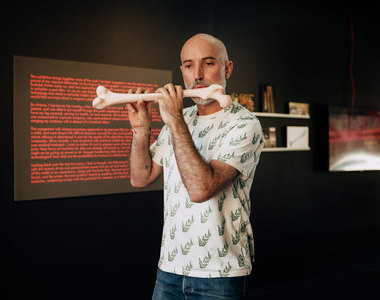

09 July 2019 | Story Nadia Krige. Photo Brenton Geach. Read time 7 min.

Having grown up living in seven different countries – attending school in five of those – Ingrid Brudvig’s desire to grapple with the complexities of cultural identity started at a young age. It was her quest to understand her own place in the world that sparked her interest in anthropology, the field in which she will be receiving her doctoral degree on Friday, 12 July 2019.

“I’ve always had a profound questioning of what it means to belong when you identify across many different places and geographies,” Brudvig explained.

“So, I’ve made it my life mission to better understand this question of culture and recognising that it has so much potential to bring people together… but also [to be] used as a tool of social control and division.”

Through her work as gender policy manager at the World Wide Web Foundation, Brudvig has also developed a keen interest in how the spread of digital technologies has impacted our lives, identities and society as a whole.

“As we’re moving more and more into this technological age, there’s such an emphasis on STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics),” she said.

“But I think it’s really important that we return to the humanities and liberal arts to better understand and deal with these profound changes in our society and in our individual lives.”

“I think now, more than ever, we need to understand and develop research and new discourse around the ‘frontier-ness’ of identity and belonging.”

New frontiers of (im)mobility

Brudvig noted that while digital technologies continue to expand – effectively creating more global and interlinked spaces of expression, association, self-representation and economic opportunity for more people – a paradoxical paradigm is concurrently unfolding where widespread nationalist rhetoric has led to the stringent policing of borders, and the drawing of boundaries between who belongs and who doesn’t.

In this climate of fear and distrust, freedom of movement has all but become a luxury, particularly for those who have been robbed of their own national identity and human rights, and who seek integration in societies elsewhere.

Brudvig used the term “(im)mobility” to capture the juxtaposition between the seemingly boundlessness of virtual spaces and the increasing global clampdown of movement across physical borders, control of identities, and fear of difference.

“I [am interested in] how identity is negotiated between physical and virtual spaces. I call this a frontier space,” she explained.

“I think now, more than ever, we need to understand and develop research and new discourse around the ‘frontier-ness’ of identity and belonging.”

It is within this context that Brudvig set out to understand how the use of digital technologies may offer the globally connected Somali diaspora in South Africa an alternative means of mobility.

In her doctoral thesis, she explored the intersection of (im)mobility, physical and virtual space, and new configurations of belonging in this increasingly digital world.

Her interest in this specific community was inspired by the ethnographic research she conducted in Bellville, in Cape Townʼs northern suburbs – a popular destination for Somali migrants – as part of her masterʼs degree.

Under the supervision of Professor Francis Nyamnjoh from UCT’s School of African and Gender Studies, Anthropology and Linguistics, she investigated conviviality in Bellville and why it has come to be seen by Somali migrants as not only a place of entrepreneurial activity, but also as a place of safety.

“So, there is this distance, but technology enables families to be together in spite of it.”

During this research, she noted the important role the internet plays in helping Somali migrants navigate a complicated sense of belonging and felt called to investigate it in more depth.

The internet as social lifeline

Embarking on her doctoral study, she found that within a community that has been subject to various exclusions – including political unrest, persecution of journalists and limited access to rights, and experiences of violence such as xenophobic attacks on Somali shopkeepers in informal settlements throughout South Africa – digital technologies and social media have become lifelines to a growing global diaspora, offering invaluable opportunities to continue social and cultural traditions.

“It was explained to me that festivities or religious events, weddings, for instance, are usually recorded and shared via YouTube or Facebook Live,” she said.

“So, there is this distance, but technology enables families to be together in spite of it.”

Situating her work in what she terms “feminist digital ethnography”, Brudvig was particularly interested in analysing the role of ICTs (information and communication technologies) and the internet in the lives of Somali women.

By connecting with one another through Facebook groups and sharing their experiences in blog posts and online magazines, many Somali women around the world have found an unprecedented measure of empowerment online.

Brudvig noted, however, that these experiences are also situated in a broader context of social anxiety about the public participation of women on and through the internet, and the impact it may have on family and cultural life.

Even though a fair amount of research has been conducted around Somali communities in South Africa, it has been greatly focused on xenophobia, violence against shopkeepers and community peacebuilding.

“There’s a large and growing gender gap in the access [to] and use of the internet.”

Within this context, the inclusion of women and women’s experiences has been comparatively limited. Brudvig’s study, thus, makes an important contribution to the field of anthropology in South Africa.

Working to minimise the digital gender gap

As she prepares to close the chapter on her PhD study, Brudvig said that – through her work at the World Wide Web Foundation – she is looking forward to doing more research on women’s rights online and ensuring that the open web is affordable and accessible for everyone.

“There’s a large and growing gender gap in the access [to] and use of the internet,” she explained.

“So, I’m interested in gaining a better understanding of this and conducting research that can inform advocacy strategies to engage government on creating more gender-responsive technology policies.”

She added that she hopes to see more ethnographic studies on women and digital technologies, as well as gender equality in the digital age.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.