The test for higher education readiness

10 October 2024 | Story Kamva Somdyala. Photos Lerato Maduna. Voice Cwenga Koyana. Read time 4 min.

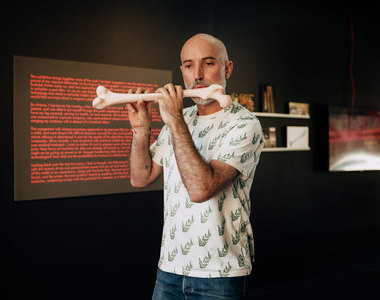

Emeritus Professor Alan Cliff, from the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Centre for Higher Education Development (CHED), has spent 30 years researching literacy testing for higher education readiness, offering critical insights into access, redress, and academic success for diverse students.

His work, informed by two major projects – the Alternative Admissions Research Project and the Centre for Educational Assessments – focuses on the challenges of access, redress, and success in higher education. This extensive research is documented in a book titled Thirty Years of Literacies Testing at the University of Cape Town.

The book comes at a critical time as the country celebrates 30 years of democracy, which has given people an opportunity to take stock of just how far the country has come in several areas, including education. UCT News recently had a conversation with Professor Cliff, who reflected on the long-running project.

“Given the length of the project, I thought it was time to ask critical questions of the project: What has it achieved? Why did the project start? What were the aims, and, have those aims shifted because of the expectation that the work is not static and is bound to shift?” Cliff began.

“The first phase of the work is connected to issues of student redress – and that theme still continues – but tracking it (for purposes of the book) happened up until about 2003. By about 2005, the second phase of the research had become quite strong, and that was the phase dealing with looking at the reliability of the then school-leaving examination and how the project could help us to have a stable assessment across time to help understand the new National Senior Certificate (NSC) examination.”

“We knew, that because of the social engineering and the historical politicisation of the apartheid-era schooling system, many students might be talented but were not achieving what they ought to in the school-leaving examination,” Cliff added.

The book explains the design, development, and rationale of standardised academic literacy tests tackles the challenges of access, redress and success in higher education; and shows how literacy tests can respond to them.

How to cope

Much of the origins of the research happened at a time when UCT was trying to make a serious attempt to change the demographic in the student body, but also to be sure to admit students that could be successful. “But, given the schooling system, there was an appreciation that one couldn’t simply admit students without comprehensive and holistic support systems, because the admitted students would potentially fall victim to what was then known as the ‘revolving door syndrome’ (in first year, gone by end of first year).”

Cliff added: “So the assessment project chose as its base the notion of academic literacies rather than achievement as embodied in the school-leaving examination. In addition to exam results, we also wanted to see to what extent would they be able to cope with the conventional, standard, reading, writing, thinking demands that would be placed on them when they reached higher education.”

“We needed to do something that was credible to the higher education institution, making a judgment on an objective measure.”

By his own account, there’s a huge amount of data which accompanies this body of work. Cliff revealed that they tested hundreds of thousands of learners across the country and without focusing on individual students, they were able to sample to see what their learnings can tell them about literacies systems building. “This is a project that was always meant to be complementary to achievement-oriented ways of assessment,” he said.

Student representation

“We needed to do something that was credible to the higher education institutions, making a judgment on an objective measure, ie testing. In other words, going beyond asking a student if he/she is ready for higher education and taking that answer as proof-positive. The value of this is beyond admissions. The data we have been collecting over 30 years can tell us a lot about what the sector could do to respond to teaching and learning sector demands and to higher education responsiveness.”

He concluded: “[The book will be relevant] to people who are interested in assessment design (doing better at it); people who want to bring literacies and discipline learning into a common conversation; language-of-instruction and mother-tongue learning; and people working with a diverse set of student intakes. At the end of the day, it’s about how best to support students and how we best enable all students to see themselves better represented in the higher education space. The book focuses a great deal on the need for responsive educational programme provision, curriculum change and the development of literacies teaching in both foundation and mainstream teaching.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.