Stories shared in moving re-memorisation project

02 March 2020 | Story Kim Cloete. Photos Lerato Maduna. Read time 7 min.

The views of everyone from cleaners and surgeons to nurses and handymen form part of the inspiring Foyer Re-memorisation Project at the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital in Cape Town.

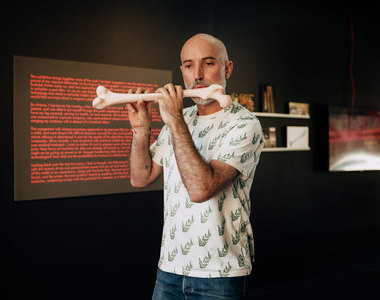

The permanent exhibit, which was opened on Friday, 28 February, relays the experiences and stories of staff members through photographs and words. The project was initiated by the Transformation Action Group in the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) Department of Paediatrics and Child Health as part of its goal to build a community of care and belonging at the hospital.

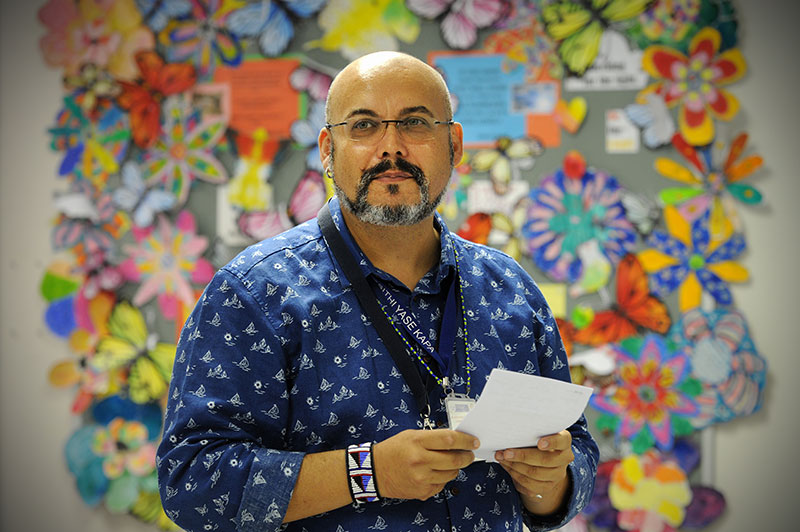

“The Foyer Re-memorisation Project addresses the issue of how we transform a physical space in our place of work to make everyone feel that they belong and that their contributions are valued. This applies to staff at every level, students, parents and patients,” said senior specialist in the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Dr Marc Hendricks.

In the exhibit, staff members, some of whom have worked at the hospital for up to 40 years, share their views about the changes and challenges they have faced up until now.

“The exhibit aims to shine a light on the physical and ideological changes which the hospital has undergone from its apartheid past to its current transforming self,” said head of UCT’s Department of Paediatrics and Child Health, Professor Andrew Argent.

Staff members have not shied away from the tough circumstances many of them had to work under. Some have told painful stories of feeling excluded and mistreated; others relay how black patients were discriminated against.

“People were professionally and personally hurt as a result of apartheid and that can’t be swept under the rug. We can’t choose the pieces of our history that we like and hold those up, and then not speak about the others. And so, the re-memorising is about bringing the story into balance,” said Hendricks.

Ongoing transformation

The exhibit shows that the process of transformation is an ongoing journey, but it also highlights some of the marked changes since the end of apartheid and the early years of democracy in South Africa.

“Things have changed drastically. In Oncology, there weren’t a lot of black people working here and in the hospital as well. There was difficulty in being accepted by the parents because I was just this young girl from the rural areas. So, we grew together. At the end of the day, it’s all about working together,” said Sister Primrose Mjikeliso in her interview, which is displayed together with her photograph.

Registered nurse Sister Zainunisa Brown said she was pleased to have been interviewed for the project.

“It’s good to be part of these stories – from the woman who delivers the clean linen in the morning to the specialist working in surgery. It gives me a full picture of the hospital. Often we forget about the whole person. This is trying to recognise that … of where you come from and where you are heading.”

“There is a whole team working behind the scenes that keeps things going.”

Dr Anita Parbhoo, medical superintendent of the Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital, said she was very proud to be part of efforts over the past few years to improve the organisational culture in the hospital. She also commended staff across the board.

“Clinicians often get a lot of the recognition and accolades, but in a hospital like this there is a whole team working behind the scenes that keeps things going.”

Argent encouraged people to read the stories and reflect on them.

“The process is one through which we aim to heal our history and move forward as a stronger, more unified and more connected community that places mutual respect at its centre.”

Symbolic significance

The Red Cross War Memorial Children’s Hospital is a beacon of light for many patients and families and sees 250 000 children a year. The exhibit is near the entrance to the Oncology ward and is an important link to other areas of the hospital. Hendricks said this had symbolic significance.

“Entrances are the first point of interaction between a building and its occupants. Entrances therefore represent who is ‘included’ and who is ‘not included’. Historically there was a time where facilities at the hospital were racially segregated, and your carers were determined by the colour of your skin,” he said.

“Thankfully we have moved past that time to enjoy the integrated services that we have today, but it is important to acknowledge our history and the difficulties that it may have caused for people – both personally and professionally.”

Hendricks hopes that the exhibit will be a way “to teach, to inspire and to remind us of our social and personal responsibility to each other”.

“It is important to acknowledge our history and the difficulties that it may have caused.”

He encouraged doctors and students, patients and their families, hospital personnel and donors to see the exhibit.

“I want to walk my students through this, just to say: ‘Remember where you are. Remember the privilege that you have here, that this moment has been bought and paid for by other people. Understand the gravity of the place that you stand in, because that’s important.’ ”

Bringing people together

Argent commended the “breadth of vision” of the Transformation Action Group, which was formed in the department in 2015. Since then, it has engaged in various ways to address issues of representation, access, education and training as well as institutional climate.

“I think they’ve had this very broad view of transformation that at the end of it, it’s making sure that everyone is treated with deep respect and acknowledged for what they do, and I think that is reflected here … that it doesn’t matter what your title is, if you’re part of this community, you’re important and relevant.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.