District Six: Lessons in remembering

11 February 2021 | Story Carla Bernardo. Photos Lerato Maduna. Voice Neliswa Sosibo. Read time 8 min.

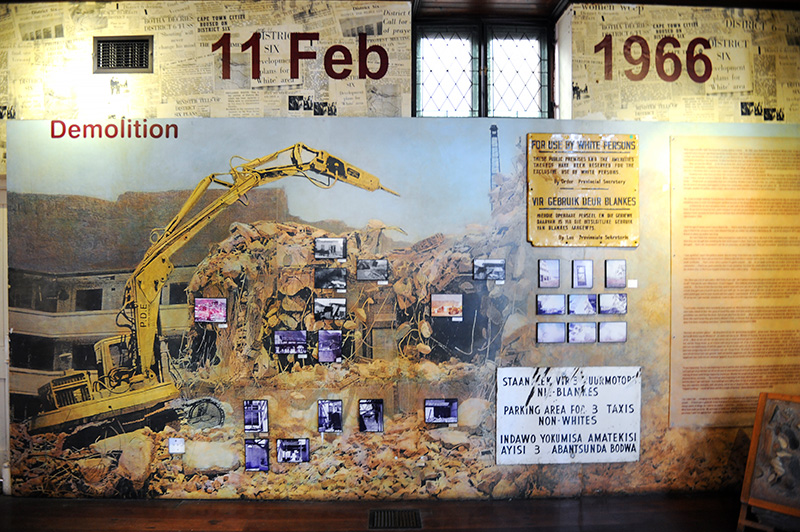

Memories of District Six are as varied and diverse as the community that inhabited the inner-city area before being forcibly removed by the apartheid government. Some of these memories are about the rich politics of District Six, others about its cultural contributions. The 55th anniversary of the declaration of District Six as a whites-only area on 11 February 2021 offers a moment to reflect on what it means to so many.

There are some who remember District Six as a veritable melting pot while others have chosen to remember the area through a racialised apartheid lens. But even with this “contested history” of District Six, there are many lessons to be learnt, particularly when confronting issues of gentrification, homelessness, diversity and identity.

Mandy Sanger, the head of education at the District Six Museum and a University of Cape Town (UCT) alumna, is using the history of District Six to inform the present. Sanger, whose family was forcibly removed from Newlands, Claremont and Harfield Village, has managed the education arm of the museum for around 15 years, working with young people in learning journeys that are part of the museum’s Re-imagining the City workshops.

“A lot of my work at the District Six Museum is about ensuring that there is continuity and depth in the understanding and interpretation of the apartheid experience in our democracy,” she said.

These learning journeys see young people, including UCT students, developing understandings of apartheid and colonialism and linking these to the world they live in. And they’re simultaneously invited into what the museum terms “brave spaces” where they are encouraged to think, argue and contest ideas. The history of District Six is vital in this process.

Young people are taught to work with the different vantage points that people had in District Six, their various political affiliations and the many ways in which people resisted apartheid. In doing so, a new generation is being taught about living with difference and learning from the violence of our past.

Living together

Part of the learning journeys draws on the rich oral histories and contributions of former residents that make up the museum. There are memories of the area’s rich political history: the non-racial movement, activists and freedom fighters such as Marcus Solomon and Cissie Gool, artists like Lionel Davis, and Nelson Mandela’s visits to the Stakesby-Lewis Hostel.

“It’s a creole community rather than how the apartheid Population Registration Act [of] 1950 aimed to define it as a fixed racial category: ‘Cape Coloured’.”

There is also a “very dominant popular memory of District Six” that centres around its diversity. Sanger explained that because of its proximity to the harbour, inhabitants of District Six came from a long history of people mixing and remixing from many sources.

“It’s a creole community rather than how the apartheid Population Registration Act [of] 1950 aimed to define it as a fixed racial category: ‘Cape Coloured’,” she said.

Some of the memories take on this apartheid racialised lens and remember District Six as a coloured community, thereby erasing the Xhosa-speaking people who were first forcibly removed from the area in 1901, scapegoats for the bubonic plague that entered the Cape through the harbour. Equally problematic are the memories of ‘coloureds’ as the ‘coons’, as being in cahoots with their masters and laying claim to European heritage, as opposed to African ancestry.

But, as those on the learning journeys come to realise, there are many who connect minstrels and related rituals to slave heritage and resistance, to the rhythms that came from places such as Angola, Mozambique, Indonesia, Malaysia and New Orleans. At various moments in Cape Town’s history, people and rituals from outside mixed and mingled with indigenous people over centuries, culminating in the heyday of District Six in the 1950s and 1960s as a culturally vibrant inner-city hub of writers, artists, musicians and performers.

“District Six had just about all religious faiths, including many well-known atheists, and people went in and out of different religions.”

Memories centred around religion also speak to the diversity of the area and how people lived with difference in District Six.

“District Six had just about all religious faiths, including many well-known atheists, and people went in and out of different religions,” said Sanger.

It’s one of the few places in the world where you’d find Muslims with Jewish surnames such as Benjamin or Levy. Sanger particularly enjoys it when individuals trace their family’s histories and find that they started as one religion, changed to another and then their children changed religion yet again.

There are also many oral histories of people of different faiths living on the doorstep of another’s place of worship and of Muslims taking part in Christmas rituals.

“One thing we often laugh at when residents tell their stories is there’s always a Mohammed who played Jesus in some church performance of a biblical story,” said Sanger.

This, said Sanger, is what makes District Six special and holds lessons for society today where religion is often a divisive factor in communities. But Sanger makes it clear that District Six was not necessarily the “tolerant place” people often remember; rather, people found ways to live together even in disagreement.

Reversing political legacies

In addition to lessons about colonialism, apartheid and living with difference and diversity, there are many more lessons to be learnt from District Six and the museum.

For instance, international museums, particularly European museums with long histories that have now become set in stone, can look to the District Six Museum’s methodology and how they work dialogically with and in the community as they grapple with change. They have never needed to find ‘community’, as the museum’s “work is almost always embedded in the displaced community”.

More broadly, the stories of District Six make clear the importance of building egalitarian societies by learning from the violence and wars of our past and learning to live with one another’s differences.

“We believe that these lessons are not just applicable to the people and the families affected by District Six. People experiencing all forms of displacement in the world can learn valuable lessons from our stories, as we do from theirs, in expressions of solidarity” said Sanger.

And beyond the learning journeys, the museum hopes that these lessons find their way into the process of returning to District Six. For the museum, returning should not just be a bureaucratic ‘bricks and mortar’ process. Instead, as noted by Sanger, there needs to be “deeper political thinking”.

“Very many millions of people were forcibly removed in South Africa and displaced. So, there has to be a point when many of us say … return really is about solving the inequality in our society,” said Sanger.

“Post-apartheid democracy and return must be about reversing the political legacies that we still live with in society.”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please view the republishing articles page for more information.

Listen to the news

The stories in this selection include an audio recording for your listening convenience.